When the 18-year-old Ethel Barrymore informed her father that she was engaged, he wired:

CONGRATULATIONS LOVE FATHER

When she informed him she’d broken it off, he wrote:

CONGRATULATIONS LOVE FATHER

When the 18-year-old Ethel Barrymore informed her father that she was engaged, he wired:

CONGRATULATIONS LOVE FATHER

When she informed him she’d broken it off, he wrote:

CONGRATULATIONS LOVE FATHER

Fielding positions in “Who’s on First?”:

When Dodgers shortstop Chin-Lung Hu singled in a 2007 game against the Padres, announcer Vin Scully said, “And Hu’s on first.”

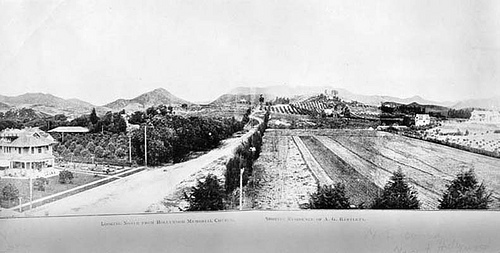

That’s the intersection of Hollywood and Vine in 1906.

Seven years after this photo was taken, Cecil B. DeMille was searching for a western location to film The Squaw Man. He sent this telegram to his New York partners:

FLAGSTAFF NO GOOD FOR OUR PURPOSE. HAVE PROCEEDED TO CALIFORNIA. WANT AUTHORITY TO RENT BARN IN PLACE CALLED HOLLYWOOD FOR $75 A MONTH.

Sam Goldwyn responded:

AUTHORIZE YOU TO RENT BARN BUT ON MONTH-TO-MONTH BASIS. DON’T MAKE ANY LONG COMMITMENT.

Years later Marilyn Monroe would write, “Hollywood’s a place where they’ll pay you a thousand dollars for a kiss and fifty cents for your soul.”

Longest game of Monopoly:

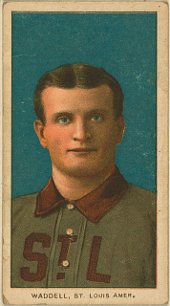

1903 in the life of erratic pitcher Rube Waddell, cataloged by Cooperstown historian Lee Allen:

“He began that year sleeping in a firehouse in Camden, New Jersey, and ended it tending bar in a saloon in Wheeling, West Virginia. In between those events he won 22 games for the Philadelphia Athletics, played left end for the Business Men’s Rugby Football Club of Grand Rapids, Michigan, toured the nation in a melodrama called The Stain of Guilt, courted, married and became separated from May Wynne Skinner of Lynn, Massachusetts, saved a woman from drowning, accidentally shot a friend through the hand, and was bitten by a lion.”

And that was just 1903. In one game against the Athletics, Waddell was at bat in the eighth inning with two out and a tying run on second. The catcher threw to second, trying to pick off the runner, but overthrew, and the ball went into the outfield. The runner took off for home. As he rounded third, the center fielder hurled the ball in to home plate …

… and Waddell, to everyone’s horror, knocked it out of the park.

He was declared out for interference. “They’d been feeding me curves all afternoon,” he told a flabbergasted Connie Mack, “and this was the first straight ball I’d looked at!”

On the morning after Jack Benny died in 1974, his wife, Mary, received a single long-stemmed rose. Another arrived the next day, and the next. For the first few weeks she was too numb to wonder where they were coming from, but eventually she called the florist to inquire.

He told her that Benny had visited the shop some years earlier to send a bouquet of flowers to a friend. As he was leaving, he suddenly turned back and said, “If anything should happen to me, I want you to send Mary a single rose every day.”

She continued to receive them every day until June 30, 1983 — when she herself passed away.

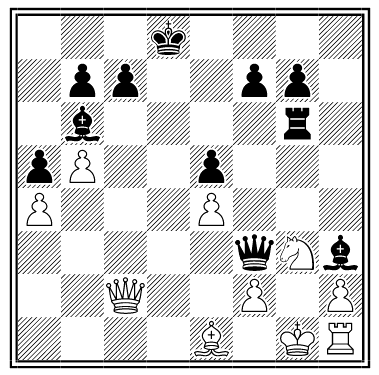

An oddity from Tristsky-Folk, 1896:

Desperate to stop mate on g2, White plays Qd1+. Black takes the queen:

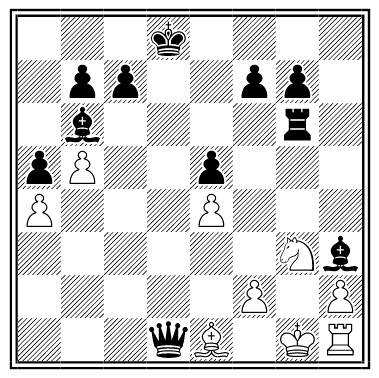

And that’s the end of the game — White has no moves!

In the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, Australian rower Bobby Pearce was leading in the quarter-final when he looked ahead and saw a family of ducks crossing his lane.

He leaned immediately on his oars and let them pass. This let Frenchman Victor Saurin catch up and then pull away to a five-length lead.

But Pearce rocketed after him and won by 20 lengths — setting a new course record and making him a favorite with Dutch schoolchildren.

One of Robert Benchley’s movie shorts required that he be suspended above a street in a tangle of telephone wires.

While waiting for the camera, he said to his wife, “Remember how good at Latin I was in school?”

“Yes.”

“Well, look where it got me.”

When Alec Guinness was filming The Swan in North Carolina in 1955, someone gave him a tomahawk purchased at a local fairground. Guinness thought it too heavy to take with him, so as he was departing he paid a porter to slip it into Grace Kelly’s bed.

Years later, while performing in London, he found the tomahawk in his own bed.

This meant war. Guinness bided his time until the princess visited America on a poetry tour, then he contacted the English actor with whom she was traveling and persuaded him to leave the tomahawk in her bed. (“Do you know Alec Guinness?” she asked him the next day. “No, I’ve never met him,” he said.)

Guinness thought no more about it until 1980, when he visited Hollywood to accept an honorary Oscar and found the tomahawk in his hotel bed. He waited until Kelly’s next tour of England and arranged to have it left in her suitcase.

She died in 1982, so that was the last laugh. There was no one to share it with — in 25 years, neither of them had ever acknowledged that this was happening.