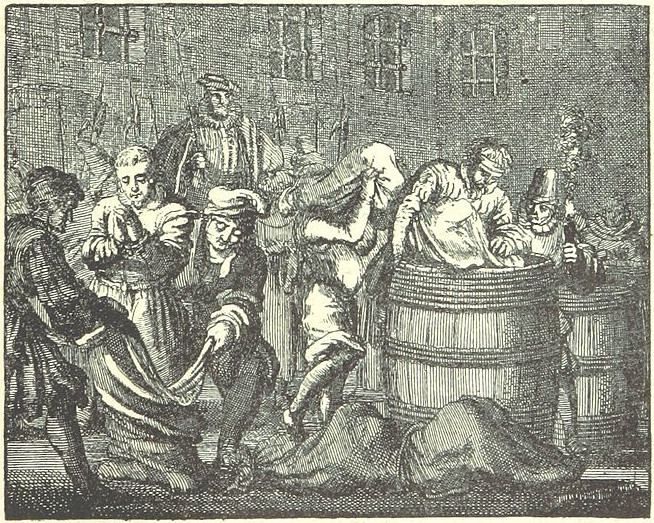

Under Roman law, subjects found guilty of patricide were subjected to poena cullei, the “penalty of the sack” — they were sewn into a leather sack with a snake, a cock, a monkey, and a dog and thrown into water.

In his Life of Artaxerxes, Plutarch describes an ancient Persian method of execution known as scaphism in which vermin devour a victim trapped between mated boats:

Taking two boats framed exactly to fit and answer each other, they lie down in one of them the malefactor that suffers, upon his back; then, covering it with the other, and so setting them together that the head, hands, and feet of him are left outside, and the rest of his body lies shut up within, then forcing him to ingest a mixture of milk and honey before pouring all over his face and body. They then keep his face continually turned towards the sun; and it becomes completely covered up and hidden by the multitude of flies that settle on it. And as within the boats he does what those that eat and drink must needs do, creeping things and vermin spring out of the corruption and rottenness of the excrement, and these entering into the bowels of him, his body is consumed.

Happily Plutarch seems to have based his account on a report by the Greek historian Ctesias, whose reliability has been questioned, so perhaps this never happened.