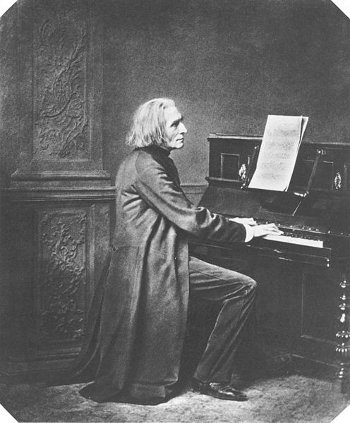

There was a composer named Liszt,

Who from writing could never desiszt.

He made polonaises

Quite worthy of praises,

And now that he’s gone he is miszt.

There was a composer named Haydn,

The field of sonata would waydn;

He wrote the Creation,

Which made a sensation,

And this was the work which he daydn.

A modern composer named Brahms,

Caused in music the greatest of quahms.

His themes so complex

Every critic would vex,

From symphonies clear up to psahms.

An ancient musician named Gluck

The manner Italian forsuck;

He fought with Puccini,

Gave way to Rossini,

You can find all his views in his buck.

— Anonymous