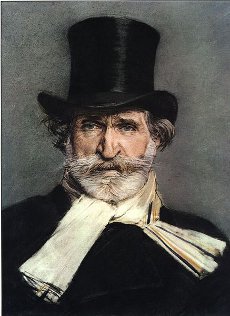

In 1832, at age 19, Giuseppe Verdi applied to study at the Milan Conservatory and was rejected.

In 1898, at the end of his career, he learned that the conservatory had decided to rename itself the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatorium.

“My God, this was all that was lacking to plague the soul of a poor devil like me who desires only to be serene and to die serenely!” he wrote to his publisher. “No, sir! Even this isn’t allowed me! What wrong have I done that I should be tormented like this?”

That’s not quite fair. He had been four years over the age limit and a foreigner to the state of Lombardy-Venetia, where the school was located. But he remembered it as “a Conservatorium that (I do not exaggerate) tried to kill me, and whose memory I should try to escape.”