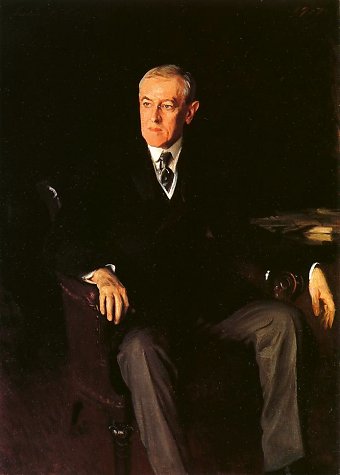

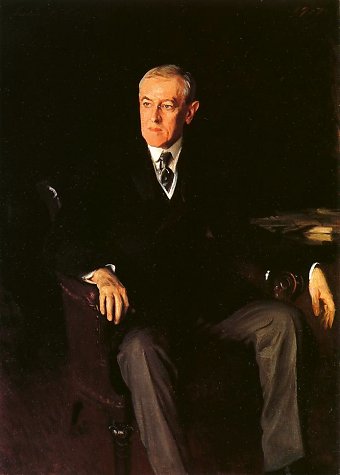

In 1915, American artist John Singer Sargent donated a blank canvas for auction at a Red Cross benefit, promising to paint a portrait of the donor who purchased it. Sir Hugh Lane bought it for £10,000 but died in the sinking of the Lusitania. He left his art collection to the National Gallery of Ireland, which didn’t know what to do with the blank canvas, so the executors finally held a referendum to ask whose portrait Sargent should paint. The popular choice, to Sargent’s surprise, was Woodrow Wilson.

At the White House Sargent confided his nerves to first lady Edith Wilson, who tried to amuse him at the easel. Still, she didn’t care for the result. “I think it lacks virility and makes Mr. Wilson look older than he did at the time,” she said later. Advisor Edward M. House said he thought it too austere, but then “I think I never knew a man whose general appearance changed so much from hour to hour.” Wilson’s opinion is not recorded.

Bonus blank canvas story: In 1951 Robert Rauschenberg painted a series of “white paintings” with the explicit intention that they appear untouched by human hands. Some patrons considered this an outright swindle when the paintings were first exhibited in 1953, but Rauschenberg wasn’t kidding: In 1962, when curator Pontus Hulten wanted to show them at Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, the paintings had been lost, so Rauschenberg simply sent him the measurements and samples of the paint and the canvas, and Hulten remade them from scratch.