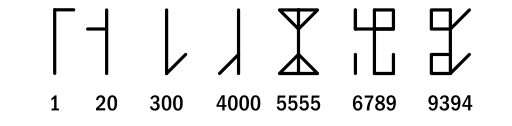

Why do people in bygone days wear such gloomy expressions? In the 16th and 17th centuries, smiling wasn’t encouraged in part because of poor dental hygiene. Louis XIV had no teeth, and the Mona Lisa may have been trying to hide gaps or stains in her smile.

Beyond the dental challenge, broad smiles and open laughter were often actively criticized, seen as reflecting a distressing lack of emotional control. Upper-class manners insisted that a boisterous laugh was a sign of poor breeding, really no better than a yawn or a fart. A French Catholic writer argued, in 1703, ‘God would not have given humans lips if He had wanted the teeth to be on open display.’ Children might smile, to be sure, but an adult should have learned to know better.

Fashionable audiences disdained laughing aloud — Molière said that this goal was not to entertain but to “correct the faults of men.” And in Protestant countries people sought to “walk humbly” in the sight of God — one writer commented that in his view, the Almighty “allowed of no joy or pleasure, but of a kind of melancholy demeanor or austerity.” This finally changed with the Enlightenment — John Byrom wrote in 1728, “It was the best thing one could do to be always cheerful.”

(Peter N. Stearns, Happiness in World History, 2020.)