“Don’t do for others what you wouldn’t think of asking them to do for you.” — Josh Billings

“A Mind-Bogglingly Slow Job”

Released in 1978, The Campaign for North Africa has been called “the most complicated board game ever released.” On each turn a player must:

- Plan strategic air missions

- Raid Malta

- Plan Axis convoys

- Raid convoys

- Distribute stores and consume stores

- Calculate spillage/evaporation of water and adjust all supply dumps

- Determine initiative

- Determine weather (hot weather = more evaporation of water)

- Distribute water

- Reorganize units

- Calculate attrition of units short of water and stores

- Begin building construction

- Begin training

- Rearrange supplies

- Transport cargo between African ports

- Bring convoys ashore

- Deploy Commonwealth fleet

- Ship repair

- Plan tactical air mission if airplanes are fueled

- Begin air mission

- Fight air-to-air combat

- Fire flak

- Carry out mission, return to base, airplane maintenance

- Place land units on reserve

- Movement:

- Move units, tracking fuel expenditure and breakdown points vis-a-vis weather

- Enemy reaction

- Move more units

- Combat:

- Designate each tank and gun as deployed forward or back

- Plot and fire barrages

- Retreat before assault

- Secretly assign all units to anti-armor or close-assault roles

- Anti-armor fire

- Adjust ammunition

- Deploy destroyed tank markers and update unit records to reflect losses

- Carry out probes and close assaults

- Release reserves

- Move rear trucks

- Begin repair of breakdowns

- Make patrols

- Repeat all movement and combat steps a second time

- Repeat all movement and combat steps a third time

His opponent then completes the same sequence, and that constitutes just one game turn.

Reviewer Luke Winkie estimated that “If you and your group meets for three hours at a time, twice a month, you’d wrap up the campaign in about 20 years.” Reviewer Nicholas Palmer added, “No doubt the first ten years are the hardest.”

Decalogue

Rules of the Anti-Flirt Club, active in the early 1920s in Washington, D.C.:

- Don’t flirt: those who flirt in haste often repent in leisure.

- Don’t accept rides from flirting motorists — they don’t invite you in to save you a walk.

- Don’t use your eyes for ogling — they were made for worthier purposes.

- Don’t go out with men you don’t know — they may be married, and you may be in for a hair-pulling match.

- Don’t wink — a flutter of one eye may cause a tear in the other.

- Don’t smile at flirtatious strangers — save them for people you know.

- Don’t annex all the men you can get — by flirting with many, you may lose out on the one.

- Don’t fall for the slick, dandified cake eater — the unpolished gold of a real man is worth more than the gloss of a lounge lizard.

- Don’t let elderly men with an eye to a flirtation pat you on the shoulder and take a fatherly interest in you. Those are usually the kind who want to forget they are fathers.

- Don’t ignore the man you are sure of while you flirt with another. When you return to the first one you may find him gone.

The club’s main purpose was to protect women from men who abused “the precedent established during the war by offering to take young lady pedestrians in their cars,” according to an article in the Washington Post. Helen Brown, secretary of the 10-member club, warned that men “don’t all tender their invitations to save the girls a walk.”

STOP

What’s the longest possible 10-word telegram? One wordplay enthusiast offered this try, at 198 letters:

ADMINISTRATOR-GENERAL’S COUNTERREVOLUTIONARY INTERCOMMUNICATIONS UNCIRCUMSTANTIATED. QUARTERMASTER-GENERAL’S DISPROPORTIONABLENESS CHARACTERISTICALLY CONTRADISTINGUISHED UNCONSTITUTIONALISTS’ INCOMPREHENSIBILITIES.

But in Language on Vacation (1965), Dmitri Borgmann observes that “we don’t like a message interrupted by two hyphens, three apostrophes, and a period.” He offered this:

PHILOSOPHICOPSYCHOLOGICAL TRANSUBSTANTIATIONALISTS, COUNTERPROPAGANDIZING HISTORICOCABBALISTICAL FLOCCIPAUCINIHILIPILIFICATIONS ANTHROPOMORPHOLOGICALLY, UNDENOMINATIONALIZED THEOLOGICOMETAPHYSICAL ANTIDISESTABLISHMENTARIANISMS HONORIFICABILITUDINITATIBUS.

It’s 45 letters longer.

Dead Letter

Last year Grant Maierhofer published Ebb, a novel written entirely without the letter A:

Ben went to school, worked in the Co-op, tried to write some but liked to be close with his friends. His friends comprised this kind of collective, this unity of spirit. Ben studied history. His friends studied too, some music, some writing, some science. They didn’t hope to extend their lives beyond this though, which left them odd. People who study, who hope to write, who hope to sing, who hope to push something through of their spirit, they often wish to flee, to go to New York, somewhere more, somewhere living, somewhere electric. These friends though they’d decided to let this be enough, their little communion with themselves, their communion of the work, which Ben enjoyed endlessly.

To describe the project, he wrote a thousand-word essay, itself without the letter A:

Why write the book? Good question. Possibly to try something out. To see where something brings you, then the things beyond this something. People write things. Sure, of course they do. People write things frequently. I write things, hm, since I like to figure the writing out. I bring problems on myself, then figure some route out of the box. The box? Stupid. Out of the box, outside the box? So stupid. Then how would you put it? The problem could be this cell, this thing you built surrounding your work. The problem could be the cell, then your working through it could be the tunneling out. This is nice. This is the thing, sure.

The essay and a longer excerpt are here. See The Void, The Great Gadsby, and Dead Letters.

Rise of the Machines

The Janken robot created in 2012 at the University of Tokyo’s Ishikawa Watanabe Laboratory has a 100 percent win rate against human opponents in playing rock paper scissors.

How? Using a high-speed camera, it recognizes within a millisecond which shape its opponent’s hand is beginning to form and chooses the appropriate winning shape.

Sweet Dreams

In an 1894 feature on peculiar furniture, the Strand describes a “suffocating bedstead” used to dispatch unwitting inn guests in the days of coach travel:

Nothing whatever of a suspicious character revealed itself to the eye of the wayfarer, yet when the scoundrel who meditated crime had satisfied himself that the man slept, he would quickly lower an interior portion of the canopy of the bedstead, firmly imprisoning him in an air-tight cavity until suffocation ensued. Struggling and shouting would be useless under such circumstances, as the weight of the box would be tremendous.

This recalls Wilkie Collins’ 1852 story “A Terribly Strange Bed,” in which a visitor at a Paris gambling house realizes the canopy over his bed is moving:

It descended — the whole canopy, with the fringe round it, came down — down — close down; so close that there was not room now to squeeze my finger between the bed-top and the bed. I felt at the sides, and discovered that what had appeared to me from beneath to be the ordinary light canopy of a four-post bed was in reality a thick, broad mattress, the substance of which was concealed by the valance and its fringe. I looked up and saw the four posts rising hideously bare. In the middle of the bed-top was a huge wooden screw that had evidently worked it down through a hole in the ceiling, just as ordinary presses are worked down on the substance selected for compression.

In his preface to the collection in which that story appears, Collins claims that it’s “entirely of my own imagining, constructing, and writing” but credits painter W.S. Herrick for “the curious and interesting facts” on which it’s based. The Strand article, published 40 years later, doesn’t mention Collins, but perhaps the idea had entered English folklore by that point. Or maybe it’s true!

Also-Ran

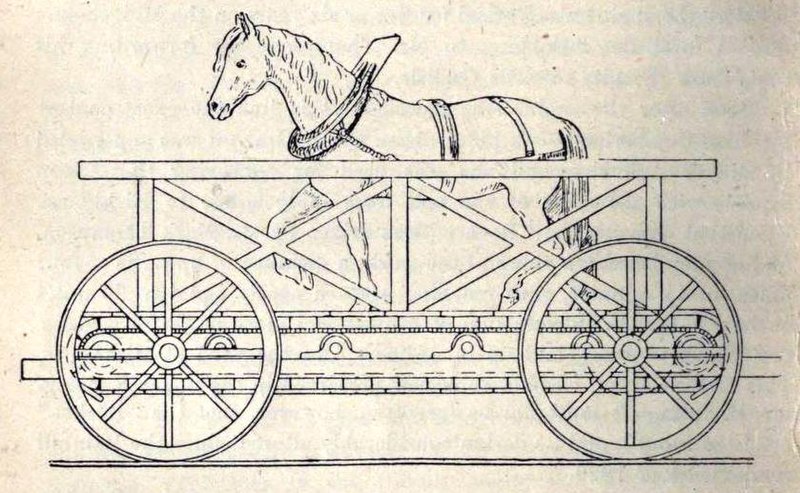

The Rainhill trials, held in October 1829 to test the suitability of locomotives to run on the new Liverpool and Manchester Railway, brought a surprising entrant: Mathematician Thomas Shaw Brandreth offered Cycloped, a car powered by a horse on a treadmill.

It was no match for the other competitors, all of which were steam locomotives. Engineer George Stephenson’s Rocket won the day — and an important place in transportation history.

“He Who Praises Everybody Praises Nobody”

Observations of Samuel Johnson:

- “We are inclined to believe those whom we do not know, because they have never deceived us.”

- “I never desire to converse with a man who has written more than he has read.”

- “Men more frequently require to be reminded than informed.”

- “To be happy at home is the ultimate result of all ambition, the end to which every enterprise and labour tends, and of which every desire prompts the prosecution.”

- “In order that all men may be taught to speak truth, it is necessary that all likewise should learn to hear it.”

- “He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man.”

- “It is strange that there should be so little reading in the world, and so much writing. People in general do not willingly read, if they can have any thing else to amuse them.”

- “I live in the crowd of jollity, not so much to enjoy company as to shun myself.”

- “Example is always more efficacious than precept.”

- “Self-confidence is the first requisite to great undertakings.”

- “Wickedness is always easier than virtue; for it takes the short cut to everything.”

- “It is very strange, and very melancholy, that the paucity of human pleasures should persuade us ever to call hunting one of them.”

- “No man will be a sailor who has contrivance enough to get himself into a jail; for being in a ship is being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned.”

- “Every state of society is as luxurious as it can be. Men always take the best they can get.”

- “Wine makes a man more pleased with himself. I do not say that it makes him more pleasing to others.”

- “If you are idle, be not solitary; if you are solitary, be not idle.”

- “The applause of a single human being is of great consequence.”

- “[S]uch is the delight of mental superiority, that none on whom nature or study have conferred it, would purchase the gifts of fortune by its loss.”

- “The world is not yet exhausted: let me see something to-morrow which I never saw before.”

Harold Nicolson wrote, “Dr. Johnson is the only conversationalist who triumphs over time.”

Plain Enough

In Jewish Bankers and the Holy See (2012), León Poliakov cites a joke current in 12th-century ghettos to justify usury between Jews.

“It consisted, it is said, of reciting Deuteronomy 23:20 in interrogative tones to make it mean the opposite of its obvious sense:

“‘Unto a foreigner thou mayest lend upon usury; but unto thy brother thou shalt not lend upon usury?'”