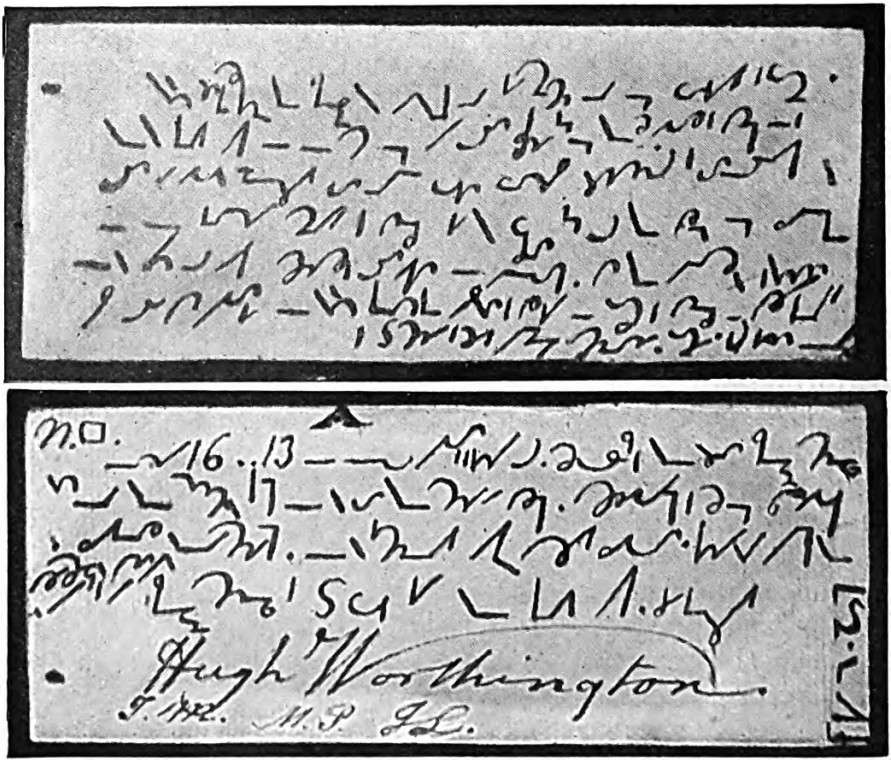

In 1614, William Nealson, a trader in Japan for the British East India Company, wrote to his friend Richard Wickham. The first half of the letter is sensible enough, and Nealson notes that his associate Mr. Cocks has already written to Wickham, “wherein he hath informed you of all business, so as for me to write thereof should be but a tedious iteration.” But then he writes “Now to the purpose” and seems to go mad:

Concerning our domestic affairs, we live well and contentedly, and believe me, if you were here, I could think we were and should be a happy company, without strife or brawling. Of late I caught a great cold for want of bedstaves, but I have taken order for falling into the like inconveniences. For first, to recover my former health, I forgot not, fasting, a pot of blue burning ale with a fiery flaming toast and after (for recreation’s sake) provided a long staff with a pike in the end of it to jump over joined stools with. Hem.

Notwithstanding I may sing honononera, for my trade is quite decayed. Before I had sale for my nails faster than I could make them, but now they lie on my hand. For my shoes none will sell, because long lying abed in the morning saves shoe leather, and driving of great nails puts my small nails quite out of request, yea, even with my best customer; so that where every day he had wont to buy his dozen nails in the morning, I can scarcely get his custom once in two or three. Well this world will mend one day, but beware the grey mare eat not the grinding stone. I have had two satirical letters about this matter from Mr. Peacock, which pleased him as little as me, but I think he is so paid home at his own weapon as he will take better heed how he carp without cause. It was not more to me, but broader to Mr. Cocks. I know the parties which I speak of you would gladly know; for your satisfaction herein I cannot make you know mine, because I think you never see her; but I think God made her a woman and I a W. For the other, it is such a one as hardly or no I know you would not dream of. But yet for exposition of this riddle, construe this: all is not cuckolds that wear horns. Read this reversed, Ab dextro ad sinistro. O I G N I T A M. What, man! what is the matter? methinks you make crosses. For never muse on the matter; it is true. I am now grown poetical.

He that hath a high horse may get a great fall;

And he that hath a deaf boy, loud may he call;

And he that hath a fair wife, sore may he dread

That he get other folks’ brats to foster and to feed.

Is this code? Nealson closes by warning “Be not a blab of your tongue” and urges Wickham to destroy “whatever I write you of henceforward.” Are these inside jokes, or references to forgotten poems or songs? William Foster includes the letter without comment in his collection of correspondence received by the company. I haven’t been able to learn anything more about Nealson, or about this seeming oddity. I found it in Giles Milton’s Nathaniel’s Nutmeg (2012).