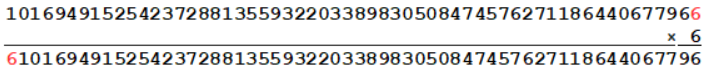

In 1983, University of British Columbia physicist Lorne Whitehead noted “a simple and dramatic demonstration of exponential growth, as in a nuclear chain reaction.” He determined that one domino can knock down another that’s about half again as large in all dimensions; since the gravitational potential energy of an upright domino is proportional to the fourth power of its size, this means that one tiny domino can set off a graduated chain reaction with impressively thunderous results.

Whitehead’s first domino was less than 10 mm high; he nudged it with a piece of cotton. The resulting chain reaction brought down a 13th domino that was 64 times as tall; an investment of 0.024 microjoules at one end had released 51 joules of energy at the other, an amplification factor of about 2 billion.

Of course, it’s possible to construct impressive chains of graduated dominoes even if they grow less dramatically than this one. Here’s a world record set in the Netherlands in 2009:

(Lorne A. Whitehead, “Domino ‘Chain Reaction,'” American Journal of Physics 51:2 [February 1983], 183.)