When the electric telegraph was making its appearance in the 1840s, it was strangely easy to confuse it with spiritualism: Both were uncanny means of talking with absent people through systems of symbols. In a bid for legitimacy, spiritualists appealed to the principles of “electrical science.” In his 1853 book The Present Age and Inner Life, Andrew Jackson Davis proposed a “spirit battery” by which a medium could improve her contact with the spirit world by asking her guests to hold a magnetic rope whose ends were dipped in water-filled buckets made of copper and zinc:

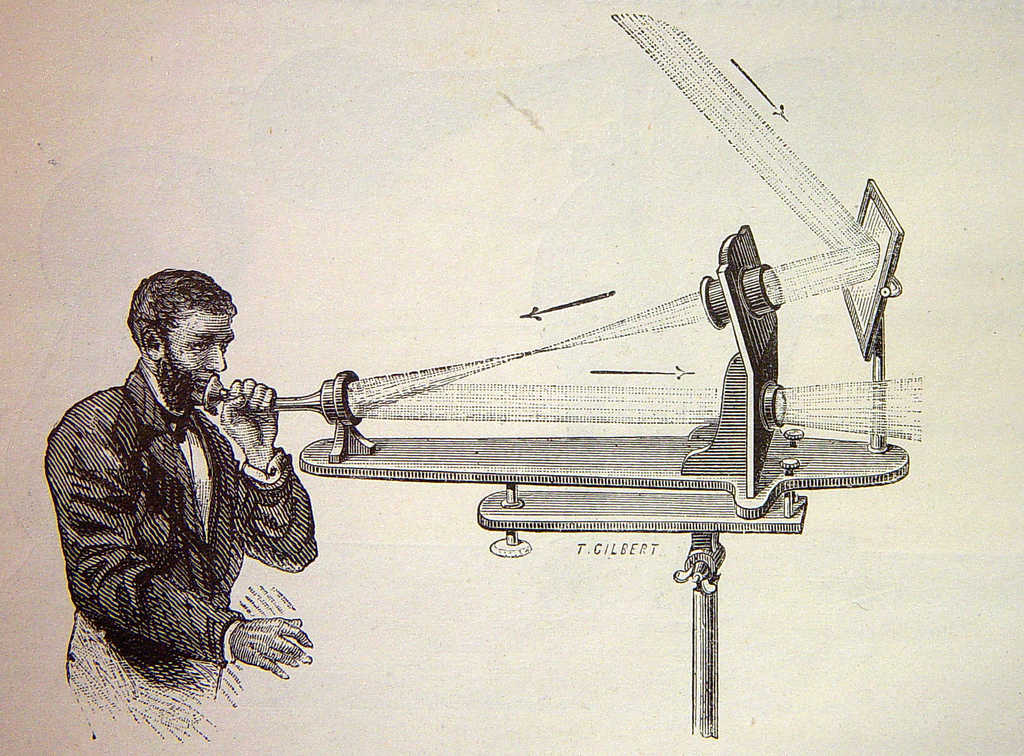

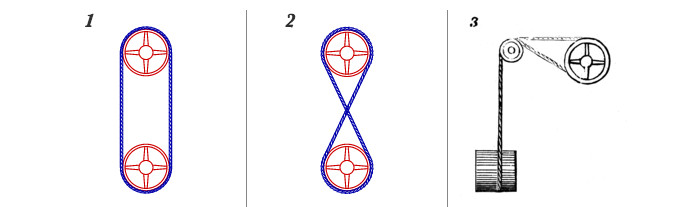

The males and females (the positive and negative principles) are placed alternately; as so many zinc and copper plates in the construction of magnetic batteries. The medium or media have places assigned them on either side of the junction whereat the rope is crossed, the ends terminating each in a pail or jar of cold water. … But these new things should be added. The copper wire should terminate in, or be clasped to, a zinc plate; the steel wire should, in the same manner, be attached to a copper plate. These plates should be dodecahedral, or cut with twelve angles or sides, because, by means of the points, the volume of terrestrial electricity is greatly augmented, and its accumulation is also, by the same means, accelerated, which the circle requires for a rudimental aura (or atmosphere) through which spirits can approach and act upon material bodies.

“We are negative to our guardian spirits; they are positive to us,” Davis wrote. “The whole mystery is illustrated by the workings of the common magnetic telegraph. The principles involved are identical.”

Alarming bonus factoid: When Samuel Morse appeared before Congress in 1838 to seek funding for an experimental telegraph line, some congressmen introduced amendments that would provide funds for research on mesmerism as well. The committee chair wrote, “It would require a scientific analysis to determine how far the magnetism of mesmerism was analogous to the magnetism to be employed in telegraphs.” When the bill came to a vote, 70 congressmen left their seats; many hoped “to avoid spending the public money for a machine they could not understand.”

(From Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television, 2000.)