When we read type we imagine that we read the whole of the type — but that is not so; we only notice the upper half of each letter. You can easily prove this for yourself by covering up the upper half of the line with a sheet of paper (being careful to hold the paper exactly in the middle of the letters), and you will not, without great difficulty, decipher a single word. Now place the paper over the lower half of a line, and you can read it without the slightest difficulty.

— George Lindsay Johnson, “Some Curious Optical Illusions,” Strand, October 1897

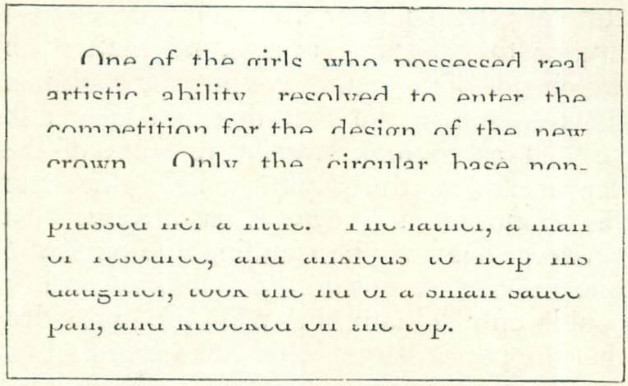

11/04/2024 UPDATE: In the experimental writing system Aravrit, devised by typeface designer Liron Lavi Turkenich, the upper half of each letter is Arabic and the lower half is Hebrew:

(Thanks to reader Djed F Re.)