From Lee Sallows:

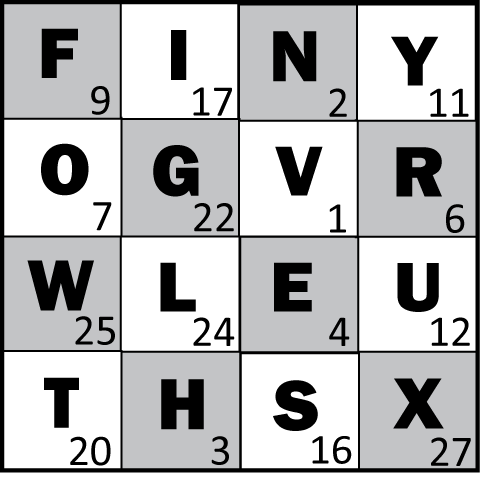

As the reader can check, the English number names less than “twenty” are composed using 16 different letters of the alphabet. We assign a distinct integral value to each of these as follows:

E F G H I L N O R S T U V W X Z

3 9 6 1 -4 0 5 -7 -6 -1 2 8 -3 7 11 10

The result is the following run of so called “perfect” numbers:

Z+E+R+O = 10 + 3 – 6 – 7 = 0

O+N+E = –7 + 5 + 3 = 1

T+W+O = 2 + 7 – 7 = 2

T+H+R+E+E = 2 + 1 – 6 + 3 + 3 = 3

F+O+U+R = 9 – 7 + 8 – 6 = 4

F+I+V+E = 9 – 4 – 3 + 3 = 5

S+I+X = –1 – 4 + 11 = 6

S+E+V+E+N = –1 + 3 – 3 + 3 + 5 = 7

E+I+G+H+T = 3 – 4 + 6 + 1 + 2 = 8

N+I+N+E = 5 – 4 + 5 + 3 = 9

T+E+N = 2 + 3 + 5 = 10

E+L+E+V+E+N = 3 + 0 + 3 – 3 + 3 + 5 = 11

T+W+E+L+V+E = 2 + 7 + 3 + 0 – 3 + 3 = 12

The above is due to a computer program in which nested Do-loops try out all possible values in systematically incremented steps. The above solution is one of two sets coming in second place to the minimal (lowest set of values) solution seen here:

E F G H I L N O R S T U V W X Z

–2 –6 0 –7 7 9 2 1 4 3 10 5 6 –9 –4 –3

But why does the list above stop at twelve? Given that 3 + 10 = 13, and assuming that THREE, TEN and THIRTEEN are all perfect, we have T+H+I+R+T+E+E+N = T+H+R+E+E + T+E+N. But cancelling common letters on both sides of this equation yields E = I, which is to say E and I must share the same value, contrary to our requirement above that the letters be assigned distinct values. Thus, irrespective of letter values selected, if it includes THREE and TEN, no unbroken run of perfect numbers can exceed TWELVE. This might be decribed as a formal proof that THIRTEEN is unlucky.

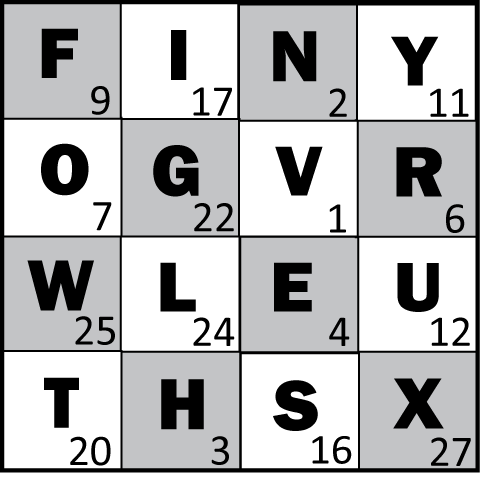

But not all situations call for an unbroken series of perfect numbers. Sixteen distinct numbers occur in the following, eight positive, eight negative. This lends itself to display on a checkerboard:

Choose any number on the board. Call out the letters that spell its name, adding up their associated numbers when on white squares, subtracting when on black. Their sum is the number you selected.

(Thanks, Lee.)