Jean-François Sudre had a unique thought in 1817: If people of different cultures can appreciate the same music, why not develop music itself into an international language?

The result, which he called Solresol, enlists the seven familiar notes of the solfeggio scale (do, re, mi …) as phonemes in a vocabulary of 2,600 roots. Related words share initial syllables; for example, doremi means “day,” dorefa “week,” doreso “month,” and doredo the concept of time itself. Pleasingly, opposites are indicated simply by reversing a word — fala is “good,” and lafa is “bad.”

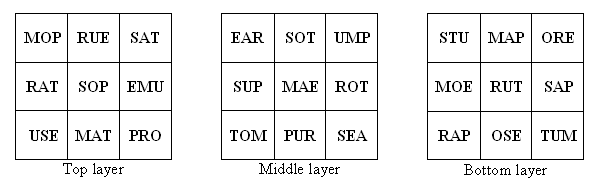

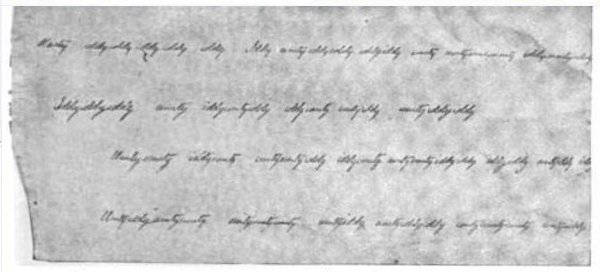

Sudre developed this in various media: In addition to a syllable, each note was also assigned a number and a color, so that words could be expressed by knocks, blinking lights, signal flags, or bell strikes as well as music.

“Imagine for a moment a universal language, translatable to colour, melody, writing, touch, hand signals, and endless strings of numbers,” writes author Paul Collins. “Imagine now that this language was taught from birth to be second nature to every speaker, no matter what their primary language. The world would become saturated with hidden meanings. Music would be transformed, with every instrument in the orchestra engaged in simultaneous dialogue. … [T]he beginning of Beethoven’s Fifth seems to talk about ‘Wednesday’ … Needless to say, obsessive fans who already hear secret messages in music would not do their mental stability any favors by learning Solresol.”

Sudre was hailed as a genius in his lifetime, and he collected awards at world exhibitions in Paris and London, but he died before his first grammar was published. An international society promoted the language until about World War I, but in the end it lost adherents to Esperanto, which was considered easier to learn.