One last unlucky elephant. In the early 1900s, Thomas Edison was locked in a historic “war of currents” with George Westinghouse. Edison wanted the nation to use direct current; Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla wanted alternating current.

That sounds like a pretty tame dispute, but Edison went to some horrific lengths to sway public opinion. To prove that AC was dangerous, he began electrocuting stray cats and dogs. He said they were being “Westinghoused.” He also secretly funded the first electric chair, which ran on AC but was underpowered — its first use resulted in “an awful spectacle, far worse than hanging,” in the words of one witness.

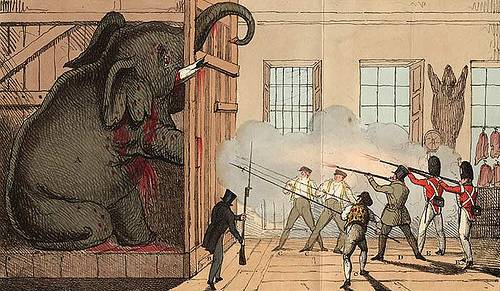

Anyway, around this time a Coney Island elephant named Topsy was condemned to death for killing three men in three years. Hanging was out, thanks to the ASPCA, so Edison suggested they send 6,600 volts of AC through her. So on Jan. 4, 1903, 1,500 people gathered at the amusement park and watched as Topsy ate carrots laced with 460 grams of potassium cyanide and was Westinghoused. She died quickly, reportedly, but Edison recorded the whole thing on film, and later played Electrocuting an Elephant to audiences around the country.

He lost the fight for DC power, though. There’s some justice.