Write the word MAYONNAISE in a circle and read it backward and you get I ANNOY AMES.

Make of that what you will.

(From Word Ways, February 1968.)

Write the word MAYONNAISE in a circle and read it backward and you get I ANNOY AMES.

Make of that what you will.

(From Word Ways, February 1968.)

Reversing the Dutch word for kidney, NIER, gives the French word for kidney, REIN.

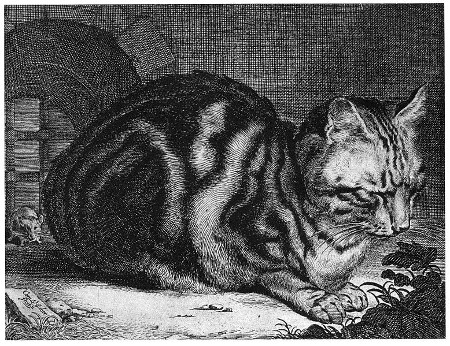

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God, duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

For this is done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

For having done duty and received blessing he begins to consider himself.

For this he performs in ten degrees.

For first he looks upon his fore-paws to see if they are clean.

For secondly he kicks up behind to clear away there.

For thirdly he works it upon stretch with the fore-paws extended.

For fourthly he sharpens his paws by wood.

For fifthly he washes himself.

For sixthly he rolls upon wash.

For seventhly he fleas himself, that he may not be interrupted upon the beat.

For eighthly he rubs himself against a post.

For ninthly he looks up for his instructions.

For tenthly he goes in quest of food.

For having consider’d God and himself he will consider his neighbour.

For if he meets another cat he will kiss her in kindness.

For when he takes his prey he plays with it to give it chance.

For one mouse in seven escapes by his dallying.

For when his day’s work is done his business more properly begins.

For [he] keeps the Lord’s watch in the night against the adversary.

For he counteracts the powers of darkness by his electrical skin & glaring eyes.

For he counteracts the Devil, who is death, by brisking about the life.

For in his morning orisons he loves the sun and the sun loves him.

For he is of the tribe of Tiger.

For the Cherub Cat is a term of the Angel Tiger.

For he has the subtlety and hissing of a serpent, which in goodness he suppresses.

For he will not do destruction, if he is well-fed, neither will he spit without provocation.

For he purrs in thankfulness, when God tells him he’s a good Cat.

For he is an instrument for the children to learn benevolence upon.

For every house is incomplete without him & a blessing is lacking in the spirit.

For the Lord commanded Moses concerning the cats at the departure of the Children of Israel from Egypt.

For every family had one cat at least in the bag.

For the English Cats are the best in Europe.

For he is the cleanest in the use of his forepaws of any quadruped.

For the dexterity of his defence is an instance of the love of God to him exceedingly.

For he is the quickest to his mark of any creature.

For he is tenacious of his point.

For he is a mixture of gravity and waggery.

For he knows that God is his Saviour.

For there is nothing sweeter than his peace when at rest.

For there is nothing brisker than his life when in motion.

For he is of the Lord’s poor and so indeed is he called by benevolence perpetually — Poor Jeoffry! poor Jeoffry! the rat has bit thy throat.

For I bless the name of the Lord Jesus that Jeoffry is better.

For the divine spirit comes about his body to sustain it in compleat cat.

For his tongue is exceeding pure so that it has in purity what it wants in music.

For he is docile and can learn certain things.

For he can set up with gravity, which is patience upon approbation.

For he can fetch and carry, which is patience in employment.

For he can jump over a stick, which is patience upon proof positive.

For he can spraggle upon waggle at the word of command.

For he can jump from an eminence into his master’s bosom.

For he can catch the cork and toss it again.

For he is hated by the hypocrite and miser.

For the former is afraid of detection.

For the latter refuses the charge.

For he camels his back to bear the first notion of business.

For he is good to think on, if a man would express himself neatly.

For he made a great figure in Egypt for his signal services.

For he killed the Ichneumon-rat very pernicious by land.

For his ears are so acute that they sting again.

For from this proceeds the passing quickness of his attention.

For by stroking of him I have found out electricity.

For I perceived God’s light about him both wax and fire.

For the Electrical fire is the spiritual substance, which God sends from heaven to sustain the bodies both of man and beast.

For God has blessed him in the variety of his movements.

For, though he cannot fly, he is an excellent clamberer.

For his motions upon the face of the earth are more than any other quadruped.

For he can tread to all the measures upon the music.

For he can swim for life.

For he can creep.

— From Christopher Smart’s Jubilate Agno, written between 1759 and 1763

Eunoia, by the Canadian poet Christian Bök, uses only one vowel per chapter:

Awkward grammar appals a craftsman. A Dada bard as daft as Tzara damns stagnant art and scrawls an alpha (a slapdash arc and a backward zag) that mars all stanzas and jams all ballads (what a scandal). A madcap vandal crafts a small black ankh — a hand-stamp that can stamp a wax pad and at last plant a mark that sparks an ars magna (an abstract art that charts a phrasal anagram). A pagan skald chants a dark saga (a Mahabharata), as a papal cabal blackballs all annals and tracts, all dramas and psalms: Kant and Kafka, Max and Marat. A law as harsh as a fatwa bans all paragraphs that lack an A as a standard hallmark.

Mark Dunn’s 2001 epistolary novel Ella Minnow Pea is set on an island that successively bans letters of the alphabet. Its discourse begins with “Thank you for the lovely postcards” and dwindles to “No, mon, no! Nooooooooo!”

Vladimir Nabokov’s 1938 novel The Gift ends with the main character, a writer, resolving to write a book about his experiences in the novel, thus promoting himself from a character to the author.

In Norman Mailer’s short story “The Notebook,” a writer’s girlfriend accuses him of being only an observer, not a participant in life. This gives him an idea, which he scribbles into his notebook: Writer accused of being observer, not participant in life by girl. Gets idea he must put in notebook. Does so, and brings the quarrel to a head. Girl breaks relationship over this. The girl breaks up with him over this.

The first story in John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse is a strip of paper: One side bears the words ONCE UPON A TIME THERE, the other WAS A STORY THAT BEGAN. The reader is instructed to cut this out and fashion it into a Möbius strip that reads “Once upon a time there was a story that began ‘Once upon a time there was a story that began “Once upon a time there was a story that began …”‘”

“It’s short on character, it’s short on plot, but above all, it’s short,” Barth told an interviewer. “And it does remind us of the infinite imbeddedness of the narrative impulse in human consciousness.”

In Jean-Louis Bailly’s 1990 novel La Dispersion des cendres, an embittered mystery writer publishes a sensational novel whose cover bears the warning IF YOU BUY THIS BOOK, YOU ARE A MURDERER. IF YOU READ IT, YOU WILL KNOW WHY. When the royalties reach a certain sum, they automatically send into action an assassin who shoots the writer.

Who done it? You did! “As cause and instrument of the murder, fully aware of perpetrating it, the reader — or at least the buyer — is in every sense the guilty party.”

(Thanks, Ole and Harold.)

Astrologer William Lilly managed to torpedo his own reputation. Nettled at rumors abroad in London, he published this advertisement in the Perfect Diurnal of April 9, 1655:

Whereas there are several flying reports, and many false and scandalous speeches in the mouth of many people in this City, tending unto this effect, viz., that I, William Lilly, should predict or say there would be a great fire in or near the Old Exchange, and another in St. John’s Street, and another in the Strand, near Temple Bar, and in several other parts of the City. These are to certify the whole City that I protest before Almighty God that I never wrote any such thing, I never spoke any such word, or ever thought of any such thing, of any or all of these particular places or streets, or any other parts. These untruths are forged by ungodly men and women to disturb the quiet people of the City, to amaze the nation, and to cast aspersions and scandals on me.

He should have held his tongue — the Great Fire of London broke out on Sept. 2, 1666, and consumed more than 13,000 houses, fulfilling the prophecy that Lilly had disclaimed.

“He must have misread the stars,” wrote Walter George Bell in Fleet Street in Seven Centuries. “Not to have forecasted the fire would not have mattered; but to have prophesied that it would not take place! The fool! the abject, intolerable fool!”

Writer Harry Mathews experimented with a bilingual vocabulary he called “legal franglais.” He compiled 425 words that are spelled identically in French and English (aside from accents and capitals). Examples:

Mets attend the sale

Mets attend thé salé

If rogue ignore genes, bride pays

If rogue ignore gênes, bride pays

As mute tint regains miens, touts allege bath

As muté tint regains miens, tout s’allège, bath

If emu ignore bonds, mire jars rogue

If ému ignore bonds, mire jars rogue

Roman delusive gent fit crisper rayon

Roman d’élusive gent fit crisper rayon

Because, ideally, the words should have no meaning in common, it’s hard to find reasonable settings for these utterances. Ian Monk proposed this example:

Il ne faut pas rôtir les oies mais plutôt les mâles de l’espèce, et en grande quantitê.

When it was Fred’s round, he told the landlord to grab their pint glasses and serve him and his three companions forthwith.

SEIZE JARS POUR FOUR.

One can attempt the same thing preserving sound rather than spelling. In Alphonse Allais’ verse, entire lines are pronounced the same:

Par le bois du djinn, où s’entasse de l’effroi,

Parle, bois du gin, ou cent tasses de lait froid.

And, combining these two ideas, one can compose a sentence that looks like French but sounds like English. Stopping before a monkey’s cage, François Le Lionnais exclaimed, “Un singe de beauté est un jouet pour l’hiver!”

“Twenty rules for writing detective stories,” by S.S. Van Dine, 1928:

“For the writing of detective stories there are very definite laws,” Van Dine wrote, “unwritten, perhaps, but none the less binding; and every respectable and self-respecting concocter of literary mysteries lives up to them.”

See Ten Commandments and Gumshoe Polish.

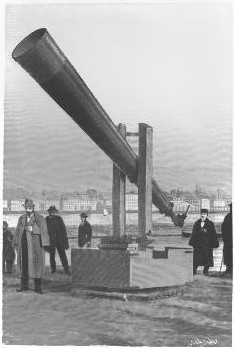

Ever since ‘weather shooting,’ as it is called in Germany and Switzerland, met with such pronounced success in Styria, upper ltaly, Hungary, and France, meteorologists have been engaged in a very wordy battle as to the merits of the scheme. That something has been accomplished cannot be denied. Indeed, so successful have been the efforts in preventing hailstorms in upper Italy that since the experiments of 1898 some twenty thousand stations have been established. At the Agricultural Congress held in Padua last November by far the greater number of the members were in favor of the building of ‘weathershooting’ stations. The congress was very decidedly impressed by an account of one of last summer’s hailstorms in the vicinity of Vicenza. So violent was this particular storm, the story runs, that for miles the land was completely devastated. But in this ravaged section, one spot was spared, because there it is asserted a number of stations had been located which had warded off the danger.

The shooting apparatus hitherto used has been very primitive in construction. For a cannon, a mortar with a funnel-like barrel was often used. In some places the funnel is fixed vertically in masonry. This method of mounting the cannon is not only crude, but also dangerous, for often enough serious accidents have occurred. In order to avoid these dangers as well as to improve the apparatus in general a Hungarian editor named Kanitz has devised a simple form of cannon which is essentially a breech-loading mortar some thirty feet in length. The mortar is journaled in a rotatable carriage, so that it can be raised and lowered and swung from side to side. The charge is a metallic cartridge of blasting powder. After the discharge a loud, shrill whistling is heard, lasting for about fourteen or fifteen seconds. French and Italian wine-growers insist that by means of the gun clouds are torn asunder, so that rain instead of hail falls.

The grape growers of five departments of the French Alps have formed an alliance for buying cannon and powder for next summer. The Italian government has such faith in weather-shooting that it supplies wine-growers with powder at the rate of three cents a pound.

— Scientific American, April 27, 1901

A puzzle by Lewis Carroll:

A bag contains one counter, known to be either white or black. A white counter is put in, the bag shaken, and a counter drawn out, which proves to be white. What is now the chance of drawing a white counter?

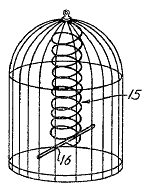

Inventors Neil and William Winton patented this “parakeet exercise perch” in 1957, in hopes of improving bird morale:

Parakeets are fast becoming common household pets and one of the first objectives of the new owner of a parakeet is to teach the parakeet to utter words that will amuse the owner thereof. …

An object of the present invention is to provide an exercising perch which will facilitate getting a parakeet in a cheerful state of mind so as he will talk or chatter more profusely.

The coil is designed so that “when a parakeet alights on any one of the coils, it will bounce up and down, sway with the weight of the bird, and oscillate back and forth.” The cage-mounted version shown here is only one option; the Wintons also envisioned a free-standing model and one that can be mounted on a wall (which is “entertaining to a parakeet possessing the ability to nose dive through a sleeve member”).

I don’t know how the parakeets responded. If they conquer the earth someday, perhaps they’ll give each of us a trampoline.