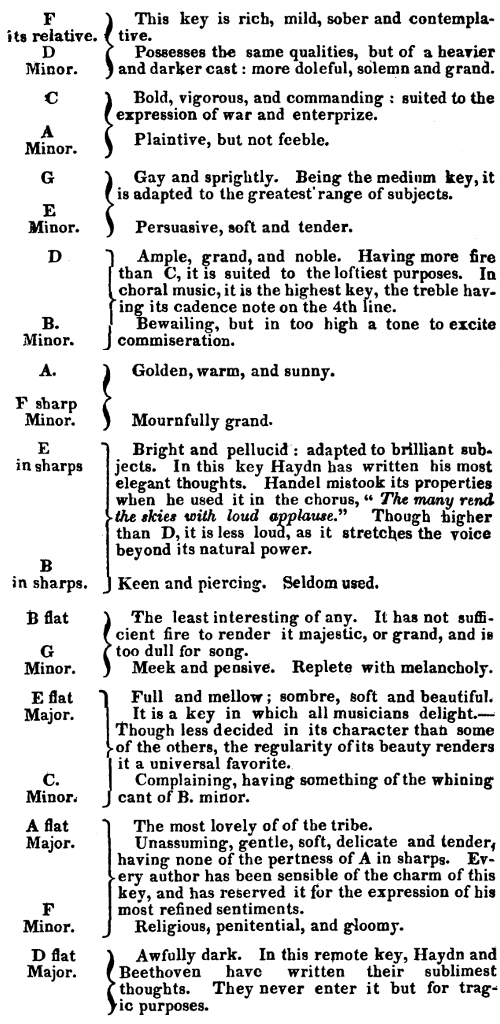

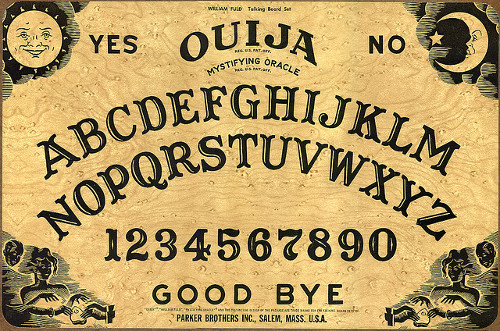

We’ve been making things awfully hard on spirits. The standard Ouija board lays out the alphabet in two simple rows, which means it’s easy for the dead to tell us about FEEDERS but terribly hard to refer to LAYAWAY, even though these words are equally long.

In the interests of better communication, Eric Iverson made a study of this for the August 2005 issue of Word Ways. Using an image of a Ouija board, he counted the number of pixels that a planchette would have to travel in order to spell out various English words. The results are dismaying: The most exhausting four-letter word, MAMA, requires fully 17 times as much travel as the simple FEED. Longer words are more consistent: The hardest 23-letter word, DISESTABLISHMENTARIANISM, requires little more work than the easiest, ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHIC. But do dead people have that kind of stamina?

What’s the answer? Iverson experimented with different layouts and found a hexagonal grid that minimizes the average travel distance for a typical word (see the link below). And he found a checkerboard grid that’s 3 percent more efficient than that. Even rearranging the letters on a standard board to ZXVGINAROFUPQ JKWCHTESDLMYB rather than the standard alphabet increases efficiency by about a third. Now maybe we can have some better conversations.

(Eric Iverson, “Traveling Around the Ouija Board,” Word Ways 38:3 [August 2005], 174-177.)