spaneria

n. a scarcity of men

spanogyny

n. a scarcity of women

spaneria

n. a scarcity of men

spanogyny

n. a scarcity of women

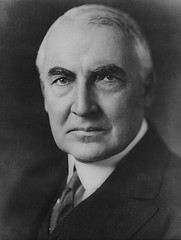

“I would like the government to do all it can to mitigate, then, in understanding, in mutuality of interest, in concern for the common good, our tasks will be solved.”

That’s Warren G. Harding, and God knows what he meant. Harding’s utterances were so impenetrable that they developed a sort of fascinated following. “He writes the worst English that I have ever encountered,” wrote H.L. Mencken, who dubbed it Gamalielese. “It is so bad that a sort of grandeur creeps into it. It drags itself out of the dark abysm of pish, and crawls insanely up the topmost pinnacle of posh. It is rumble and bumble. It is flap and doodle. It is balder and dash.”

When Harding succumbed to a stroke in 1923, E.E. Cummings wrote, “The only man, woman, or child who wrote a simple declarative sentence with seven grammatical errors is dead.”

04/08/2021 UPDATE: This example isn’t really fair to Harding — Mencken misrepresented the quote, changing a semicolon after mitigate to a comma. (Thanks, @nacreousnereid.)

The laird, so Dean Ramsay had the story sent him, once riding past a high steep bank, stopped opposite a hole in it, and said, ‘John, I saw a brock [badger] gang in there.’ — ‘Did ye?’ said John; ‘wull ye haud my horse, sir?’ — ‘Certainly,’ said the laird, and away rushed John for a spade. After digging for half an hour, he came back, nigh speechless to the laird, who had regarded him musingly. ‘I canna find him, sir,’ said John. — ”Deed,’ said the laird, very coolly, ‘I wad ha’ wondered if ye had, for it’s ten years sin’ I saw him gang in there.’

— Adam White, Heads and Tales; or, Anecdotes and Stories of Quadrupeds and Other Beasts, 1870

The armistice that ended World War I went into effect at 11 a.m. on Nov. 11 (“the 11th of the 11th of the 11th”) in 1918.

Gordon Brook-Shepherd writes: “[A]ny firing still going on ended on the last second of the tenth hour, sometimes with droll little ceremonies — as on the British front near Mons, where [a] German machine-gunner blazed off his last belt of ammunition during the last minute of the war and then, as the hour struck, stood up on his parapet, removed his steel helmet, bowed politely to what was now the ex-enemy opposite, and disappeared.”

The last casualties were not so droll. At 10:45 a.m., French soldier Augustin Trébuchon was running to tell his friends that hot soup would be served after the ceasefire when he was shot and killed.

And in the Forest of Argonne, American private Henry Gunther charged a German position just before 11:00 and was shot down. He died 60 seconds before the end of the war.

The shortest chapter in the Bible is Psalm 117. The longest is Psalm 119.

This knowledge can come in handy.

The smallest integer whose name includes all five vowels is ONE THOUSAND FIVE.

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln received this letter from a Pete Muggins in Fillmore, La.:

God damn your god damned old Hellfired god damned soul to hell god damn you and goddam your god damned family’s god dammed hellfired god damned soul to hell and god damnnation god damn them and god damn your god damn friends to hell god damn their god damned souls to damnation.

“Quarrel not at all,” Lincoln wrote on another occasion. “No man resolved to make the most of himself can spare time for personal contention.”

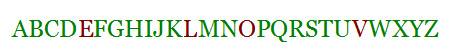

The word LOVE displays a perfect symmetry in the English alphabet: its letters are evenly distributed around the center.

In 1958, Canada held a bullfight. The Lindsay, Ontario, chamber of commerce approved $12,500 to arrange the event, apparently to promote cultural enrichment, but the transplant was shaky from the start.

Four Mexican matadors showed up on July 21, but the six bulls were delayed at the Texas border and the fight was delayed for three weeks. It finally went ahead, with three matadors, on August 22 and 23, over the objections of the Ontario SPCA, though organizers promised it would be “bloodless.”

Apparently the event itself went well, but when it was over the bulls were retired anyway, and Ontario never tried bullfighting again. Matador Jorge Luis Bernal told the Peterborough Examiner, “If a bull lives, he will be too wise for anyone to fight again. He will know the ways of the bull ring.”

In 1882, L.C. Woodman of Paw Paw, Mich., wrote to the Michigan Medical News reporting “a singular phenomenon in the shape of a young man living here”:

His name is Wm. Underwood, aged 27 years and his gift is that of generating fire through the medium of his breath, assisted by manipulations with his hands. He will take anybody’s handkerchief and hold it to his mouth, rub it vigorously with his hands while breathing on it and immediately it bursts into flames and burns until consumed. … He will, when out gunning and without matches, desirous of a fire, lie down after collecting dry leaves, and by breathing on them start the fire and then coolly take off his wet stockings and dry them. … I have repeatedly known of his setting back from the dinner table, taking a swallow of water and by blowing on his napkin, at once set it on fire. He is ignorant, and says that he first discovered his strange power by inhaling and exhaling on a perfumed handkerchief that suddenly burned while in his hands.

“It is certainly no humbug, but what is it?” Woodman asked. “Does physiology give a like instance, and if so where?”