Is every integer the sum of four perfect cubes?

Interestingly, no one knows. It’s conjectured that the answer is yes, but no one yet has been able to prove this.

Is every integer the sum of four perfect cubes?

Interestingly, no one knows. It’s conjectured that the answer is yes, but no one yet has been able to prove this.

“Good tests kill flawed theories; we remain alive to guess again.” — Karl Popper

“There are two possible outcomes: if the result confirms the hypothesis, then you’ve made a measurement. If the result is contrary to the hypothesis, then you’ve made a discovery.” — Enrico Fermi

“This particular thesis was addressed to me a quarter of a century ago by John Campbell, who … told me that all theories are proven wrong in time. … My answer to him was, ‘John, when people thought the Earth was flat, they were wrong. When people thought the Earth was [perfectly] spherical, they were wrong. But if you think that thinking the Earth is spherical is just as wrong as thinking the Earth is flat, then your view is wronger than both of them put together.’ The basic trouble, you see, is that people think that ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ are absolute; that everything that isn’t perfectly and completely right is totally and equally wrong. However, I don’t think that’s so. It seems to me that right and wrong are fuzzy concepts.” — Isaac Asimov, The Relativity of Wrong, 1988

In 2020, three researchers from UT Austin and Lancaster University examined 40,000 fictional narratives and discovered a consistent linguistic pattern. Articles and prepositions such as a and the are common at the start of a story, where they set the stage by providing information about people, places, and things. As the plot progresses, auxiliary verbs, adverbs, and pronouns become more common — words that are action-oriented and social. Near the end, “cognitive tension words” such as think, realize, and because become more common, words that reflect people trying to make sense of their world.

These patterns are consistent across novels, short stories, and amateur (“off-the-cuff”) stories. “If we want to connect with an audience, we have to appreciate what information they need, but don’t yet have,” said lead author Ryan Boyd. “At the most fundamental level, humans need a flood of ‘logic language’ at the beginning of a story to make sense of it, followed by a rising stream of ‘action’ information to convey the actual plot of the story.”

At this website you can view the graphs produced by various example narratives and even analyze your own.

(Ryan L. Boyd, Kate G. Blackburn, and James W. Pennebaker, “The Narrative Arc: Revealing Core Narrative Structures Through Text Analysis,” Science Advances 6:32 [2020], eaba2196.) (Thanks, Sharon.)

A tail behind, a trunk in front,

Complete the usual elephant.

The tail in front, the trunk behind,

Is what you very seldom find;

If you for specimens should hunt

With trunks behind and tails in front,

That hunt would occupy you long;

The force of habit is so strong.

— A.E. Housman

“One of the strangest things about life is that the poor, who need the money most, are the very ones that never have it.” — Finley Peter Dunne

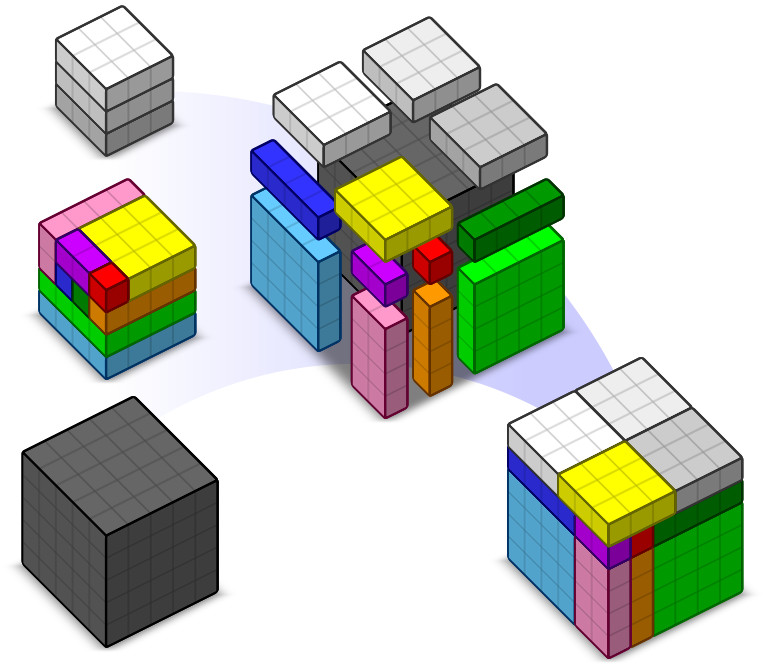

By Wikimedia user Cmglee, a visual proof that 33 + 43 + 53 = 63:

This value, 216, is sometimes called Plato’s number because it seems to correspond to this enigmatic passage in the Republic:

Now for divine begettings there is a period comprehended by a perfect number, and for mortal by the first in which augmentations dominating and dominated when they have attained to three distances and four limits of the assimilating and the dissimilating, the waxing and the waning, render all things conversable and commensurable with one another, whereof a basal four-thirds wedded to the pempad yields two harmonies at the third augmentation, the one the product of equal factors taken one hundred times, the other of equal length one way but oblong,-one dimension of a hundred numbers determined by the rational diameters of the pempad lacking one in each case, or of the irrational lacking two; the other dimension of a hundred cubes of the triad. And this entire geometrical number is determinative of this thing, of better and inferior births.

Unfortunately, Plato’s meaning is far from certain. Other values that have been proposed (with various rationales) include 1,728, 3,600, 5,040, 8,128, 17,500, 760,000, and 12,960,000. Cicero politely described the question as “obscure”; it remains open.

I don’t know anything about this; it just popped up on the subreddit r/funny:

“Someone in the Netherlands has a sense of humor.”

06/02/2025 UPDATE: Oop, no, it’s at the Dudutki ethnographic museum in Minsk! (Thanks, Nick.)

In the December 2024 issue of Recreational Mathematics Magazine, Illinois State University mathematician Sunil Chebolu demonstrates that the digits of π can be generated using the positions of stars.

The probability P(x, y) that two randomly chosen positive integers, x and y, are relatively prime is 6/π2. The stars in the night sky appear to be distributed randomly on the celestial sphere, and this suggests a novel experiment: Use the pairwise angular distances between stars to simulate a large random sample of numbers, then pick random pairs and determine the proportion of relatively prime pairs. Equating that with the theoretical probability above should generate an approximation of π.

In Nature in 1995, University of Aston mathematician Robert Matthews used the positions of 100 stars to compute π to within 0.5% of its correct value (3.12772). By expanding the sample to 1,000 stars, Chebolu got an average estimate of 3.141540567, an error of less than 0.002%.

“The above method can also be viewed as a statistical hypothesis test,” Chebolu notes. “Since the error in the estimate for π obtained using this method is pretty low, one may also argue that it supports the hypothesis that the bright stars are randomly distributed on the celestial sphere.”

(Sunil K. Chebolu, “Baking Star π,” Recreational Mathematics Magazine 11:19 [December 2024], 67-70.)

postation

n. the placing of one thing after another

consectaneous

adj. succeeding, following as by consequence

resiliating

adj. that resumes or causes to resume a former shape or position

finifugal

adj. shunning the end of something

Jason Allemann built this infinite LEGO domino ring in 2023. Sixty-four dominoes fall in a continuous loop, with a robot circulating perpetually opposite the cascade to restore the tiles to their standing state.