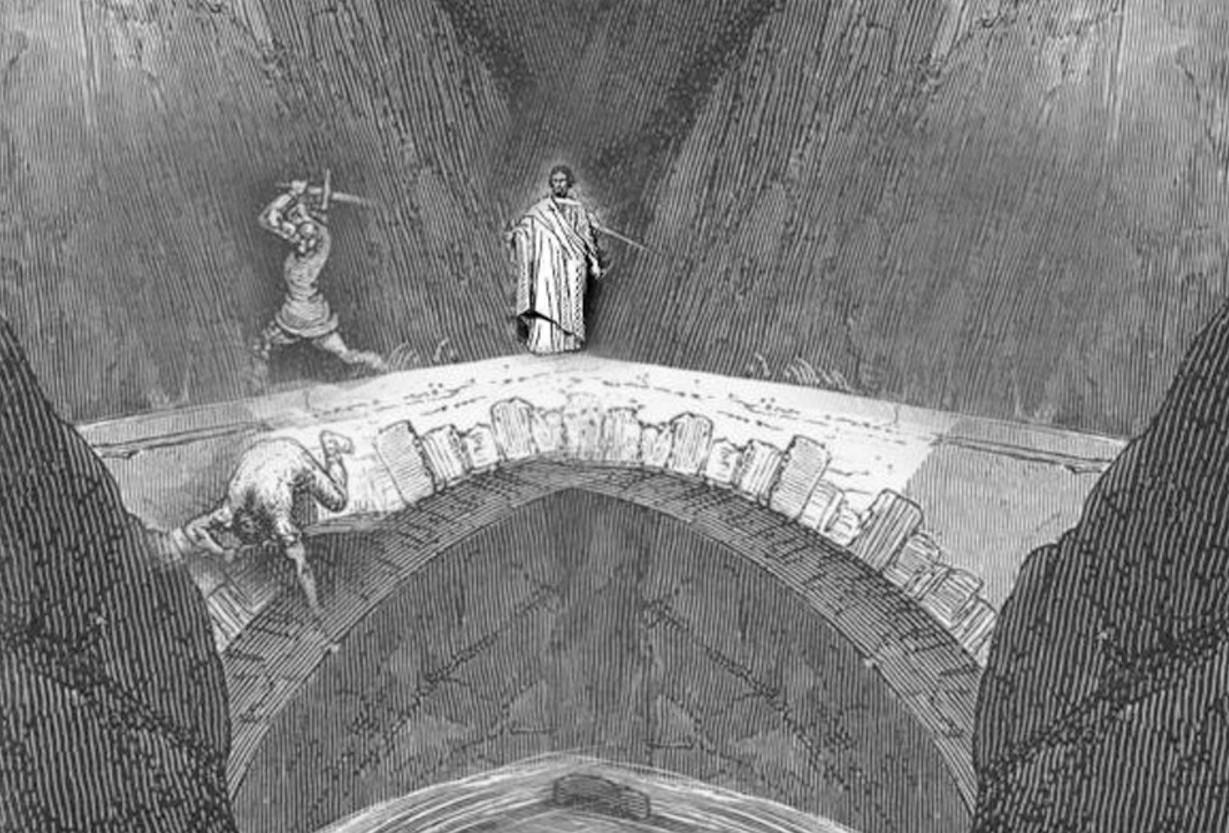

John Donne may have posed for his own funerary monument. In his Lives of 1658, Izaak Walton writes:

… Dr. Donne sent for a Carver to make for him in wood the figure of an Urn, giving him directions for the compass and height of it; and, to bring with it a board of the height of his body. These being got, then without delay a choice Painter was to be in a readiness to draw his picture, which was taken as followeth. — Several Charcole-fires being first made in his large Study, he brought with him into that place his winding-sheet in his hand; and, having put off all his cloaths, had this sheet put on him, and so tyed with knots at his head and feet, and his hands so placed, as dead bodies are usually fitted to be shrowded and put into the grave. Upon this Urn he thus stood with his eyes shut, and with so much of the sheet turned aside as might shew his lean, pale, and death-like face; which was purposely turned toward the East, from whence he expected the second coming of his and our Saviour. Thus he was drawn at his just height; and when the picture was fully finished, he caused it to be set by his bed-side, where it continued, and became his hourly object till his death …”

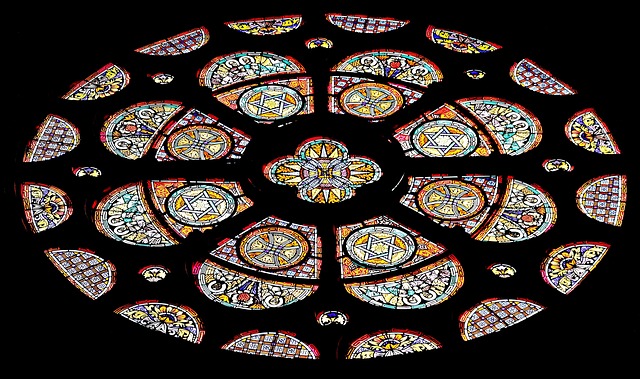

It’s not clear whether this really happened — the sketch, if there was one, has been lost. The statue stands in St. Paul’s Churchyard in London.