In 1888 New York journalist David Goodman Croly published Glimpses of the Future, a collection of predictions “to be read now and judged in the year 2000.” Excerpts:

- “The accumulation of wealth in a few hands, which is steadily going on, will unquestionably lead to a grave agitation which may have vital consequences on the future of the country. I am quite sure that the American of the twentieth century will not consent to live under a merely selfish plutocracy.”

- “Exclusive lawyer rule will yet create violent disturbance. Our whole machinery of justice is out of gear, for it is becoming more costly and inefficient. … The legal machinery grows yearly more inefficient and wasteful of time and money. Vigilance committees will exist in every part of the country if this state of things continues.”

- “Marriage is no longer a religious rite even in Catholic countries, but a civil contract, and the logical result would seem to be a state of public opinion which would justify a change of partners whenever the contracting couple mutually agreed to separate.”

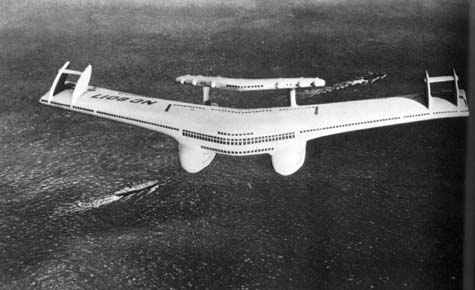

- “If the aërostat should become as cheap for travellers as the sailing vessel, why may not man become migratory, like the birds, occupying the more mountainous regions and sea-coast in summer and more tropical climes in winter? Of course all this seems very wild, but we live in an age of scientific marvels, and the navigation of the air, if accomplished, would be the most momentous event of all the ages.”

- “There will be a sub-city [in New York] under the surface of the ground for conveying people, not only from the Battery to the City Hall Park, but also from the East to the North River.”

- “True, the [chromolithograph] of to-day is looked upon as crude and inartistic; but I venture to predict that it will be so far perfected as to allow any well-to-do family to have art galleries of their own, in which will be found reproductions of all the great paintings of the ancient and modern world. The crowning glory of our age will be when the highest art is brought within the reach of the poorest purse.”

- “[In the novel of the future,] Robert Elsmere, Catherine Langham, and the other individuals, would all be reproduced pictorially. This would dispense with a great deal of description, and much of the verbiage could be cut out. Then the reader’s conception of the characters would necessarily be much more vivid. Nor is this all. Why should not a number of graphophones be made use of, giving the words of the various conversations in the tones they would naturally use? An author then would employ a number of men and women of various ages to personate his characters. They would be like the models of an artist.”

“I have no notion of being able to tell what the future has in store for us,” he wrote. “I propose simply to take up such matters as are of everyday importance, and try to think out the future with regard to them.”