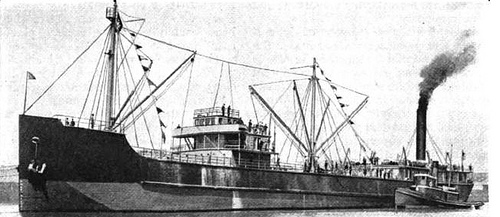

The New York Times carried a surprising headline on March 15, 1918: BIG CONCRETE SHIP AFLOAT IN PACIFIC. Noting the lack of shipyards and steel plants on the West Coast, California businessman W. Leslie Comyn had built a 7,900-ton steamer out of ferrocement.

“The huge hull, careening sharply as it slid sidewise down a steeply pitched incline, threw up a big wave in the narrow estuary, but then righted sharply and rode like a buoy,” the Times reported. “She looks as if she might have been carved out of rock, so massive is her build.”

Experts announced a new era of rapid shipbuilding, and Comyn made plans to build 54 more concrete vessels. But steel ships, though more expensive, proved lighter and faster, and by 1921 Faith had been sold and scrapped as a breakwater in Cuba.