Mystery sound frustrates people in a west Forest Grove neighborhood. Where it could be coming from? #LiveOnK2 @ 11pm pic.twitter.com/p0inj5TBr2

— Chris Liedle (@chrisliedle) February 16, 2016

Make of this what you will: In February 2016 a “mechanical scream” was repeatedly heard at night near Gales Creek Road in Forest Grove, Oregon. Described variously as a “giant flute played off pitch” and “a bad one-note violin solo broadcast over a microphone with nonstop feedback,” the sound typically lasted from 10 seconds to several minutes. It annoyed the residents, but authorities determined there were no problems with gas lines in the area, and the police department announced that the sound didn’t pose a safety hazard.

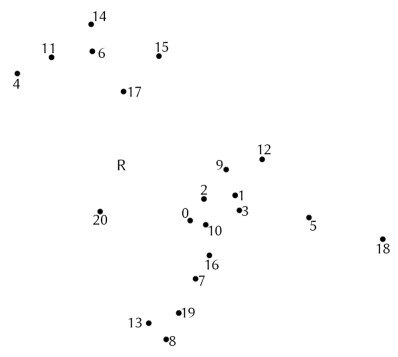

It ended as mysteriously as it had started — Pacific University physicist Andrew Dawes, who had been mapping the locations where the noise had been heard, plotted his last point on February 27, 2016. He said the results were inconclusive and didn’t suggest any single location. The police and fire departments have closed the case; Forest Grove Fire Marshal Dave Nemeyer said he suspected the noise to be “a faulty attic fan or heat pump.”