From A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper, From American Slavery, 1848:

“A large farmer, Colonel McQuiller in Cashaw county, South Carolina, was in the habit of driving nails into a hogshead so as to leave the point of the nail just protruding in the inside of the cask; into this, he used to put his slaves for punishment, and roll them down a very long and steep hill. I have heard from several slaves, (though I had no means of ascertaining the truth of this statement,) that in this way he had killed six or seven of his slaves.”

Roper himself escaped from slavery at least 16 times throughout the American South, most often from the prolifically sadistic South Carolina cotton planter J. Gooch. Examples:

“Mr. Gooch had gone to church, several miles from his house. When he came back, the first thing he did was to pour some tar upon my head, then rubbed it all over my face, took a torch with pitch on, and set it on fire; he put it out before it did me very great injury, but the pain which I endured was most excruciating, nearly all my hair having been burnt off.”

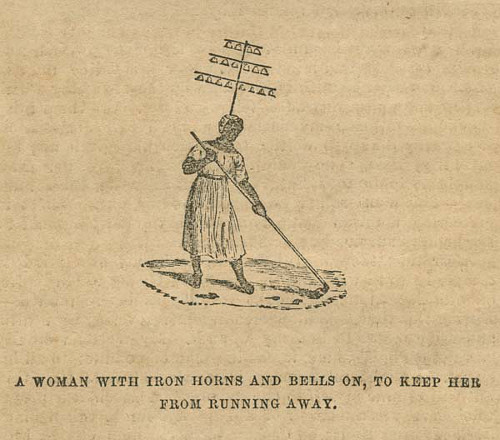

“This instrument he used to prevent the negroes running away, being a very ponderous machine, several feet in height, and the cross pieces being two feet four, and six feet in length. This custom is generally adopted among the slave-holders in South Carolina, and other slave States. One morning, about an hour before day break, I was going on an errand for my master; having proceeded about a quarter of a mile, I came up to a man named King, (Mr. Sumlin’s overseer,) who had caught a young girl that had run away with the above machine on her. She had proceeded four miles from her station, with the intention of getting into the hands of a more humane master. She came up with this overseer nearly dead, and could get no farther; he immediately secured her, and took her back to her master, a Mr. Johnson.”

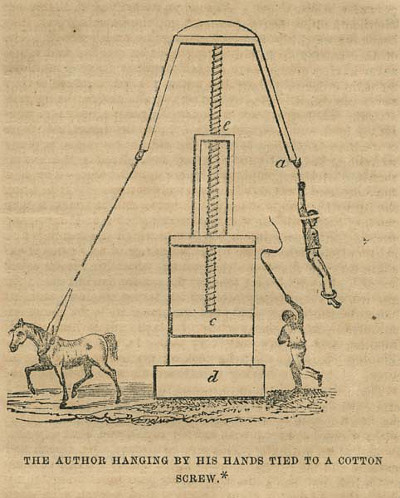

“This is a machine used for packing and pressing cotton. By it he hung me up by the hands at letter a, a horse, and at times, a man moving round the screw e, and carrying it up and down, and pressing the block c into a box d, into which the cotton is put. At this time he hung me up for a quarter of an hour. I was carried up ten feet from the ground, when Mr. Gooch asked me if I was tired? He then let me rest for five minutes, then carried me round again, after which, he let me down and put me into the box d, and shut me down in it for about ten minutes.”

“To one of his female slaves he had given a doze of castor oil and salts together, as much as she could take; he then got a box, about six feet by two and a half, and one and a half feet deep; he put this slave under the box, and made the men fetch as many logs as they could get; and put them on the top of it; under this she was made to stay all night.”

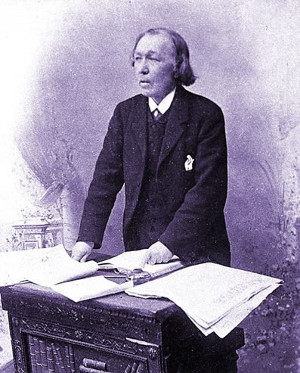

Roper finally escaped to the North in 1834 and moved to England, where he published the book and toured making abolitionist speeches. He died in 1891.