Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington D.C., and Atlanta are collinear.

(Thanks, Ryan.)

Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington D.C., and Atlanta are collinear.

(Thanks, Ryan.)

In 1940 Bertrand Russell was invited to teach logic at the City College of New York.

A Mrs. Kay of Brooklyn opposed the appointment, citing Russell’s agnosticism and his alleged practice of sexual immorality.

In the lawsuit his works were described as “lecherous, libidinous, lustful, venerous, erotomaniac, aphrodisiac, irreverent, narrowminded, untruthful, and bereft of moral fiber.”

“Although he lost the case, the aging Russell was delighted to have been described as ‘aphrodisiac,'” writes Betsy Devine in Absolute Zero Gravity. “‘I cannot think of any predecessors,’ he claimed, ‘except Apuleius and Othello.'”

Douglas Bader was beginning a promising career as a British fighter pilot when he lost both legs in a crash. But that didn’t stop him — he learned to use artificial legs and went on to become a top flying ace in World War II. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll review Bader’s inspiring story and the personal philosophy underlay it.

We’ll also revisit the year 536 and puzzle over the fate of a suitcase.

A letter to the New York Times Book Review, March 22, 1998:

To the Editor:

I read the review of Nathan Miller’s ‘Star-Spangled Men’ (Feb. 22) by Douglas McGrath, who challenged the reader to produce a sentence with three prepositions in a row, after I had picked my copy of The New York Times up from under the front porch, thankful that I didn’t have to get it down from above the porch roof, and at the same time, knowing that the delivery boy usually threw it to within a foot of the door, leaving me a quick way back in out of the cold each morning, I decided not to yell at him, especially since an argument was not something I wanted to get into outside of the house at this time of the morning, but still thinking that this was a matter that should be taken up from inside of the house by writing a letter to the editor, being careful not to use up to over three or four prepositions in a row in any sentence.

George F. Werner

Edgewood, N.M.

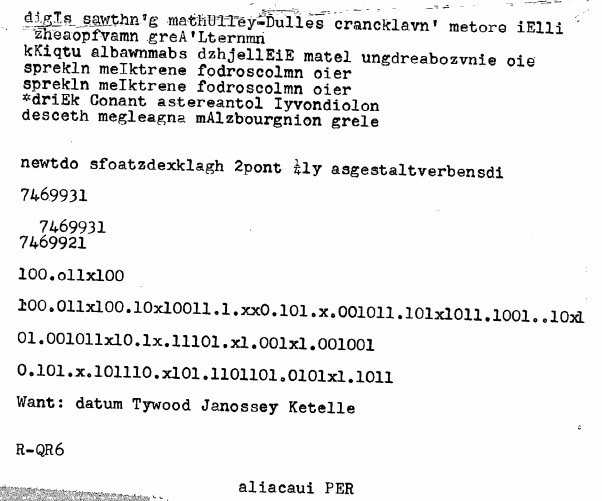

On the morning of Jan. 20, 1953, the body of 18-year-old Paul Emanuel Rubin was found at the bottom of a ditch near the Philadelphia International Airport. The coroner found there was enough cyanide in his body to “kill 10 men,” and taped to his abdomen was a 7″ x 3″ piece of paper with an enciphered message:

Rubin’s mother hadn’t seen him since the previous morning, when he’d cut some strips of adhesive tape before leaving the house. He was studying chemistry at New York University and would have had access to cyanide, but his mother said he was in good mental and physical health and hadn’t appeared worried about anything. (About 20 minutes before the body was found, the Rev. Robert M. Anderson had wished Rubin good morning; he found him “wild-eyed” and said “he was staring straight ahead and … the pupils of his eyes were dilated.”)

A friend mentioned that Rubin had been working with codes: “They’re very complicated. Anyone who reads science fiction will know what I mean.” Rubin was carrying a copy of Galaxy Science Fiction, as well as a plastic cylinder containing a signal fuse, the casing of a spent .38 caliber bullet, a “fountain pen gun” of uncertain purpose, four keys, and 47 cents. He’d had $15 when he’d left home the previous morning.

An inquest turned up nothing, and the case was closed in March. The cipher has never been solved. The Cipher Foundation has more details about the case, as well as a link to Rubin’s FBI file (8 MB PDF). The fullest account of the case that I know is in Craig Bauer’s excellent Unsolved!: The History and Mystery of the World’s Greatest Ciphers from Ancient Egypt to Online Secret Societies (2017).

In 1917, a munitions ship exploded in Halifax, Nova Scotia, devastating the city and shattering the lives of its citizens. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll follow the events of the disaster, the largest man-made explosion before Hiroshima, and the grim and heroic stories of its victims.

We’ll also consider the dangers of cactus plugging and puzzle over why a man would agree to be assassinated.

In 1950, four patriotic Scots broke in to Westminster Abbey to steal the Stone of Scone, a symbol of Scottish independence that had lain there for 600 years. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll follow the memorable events of that evening and their meaning for the participants, their nation, and the United Kingdom.

We’ll also evade a death ray and puzzle over Santa’s correspondence.

In the 1930s, before he became a children’s author, Theodor Geisel worked as an illustrator for New York ad agencies. His father, who was superintendent of parks in Springfield, Mass., began sending him the antlers, beaks, and horns of deceased zoo animals, and Ted turned them into the Collection of Unorthodox Taxidermy.

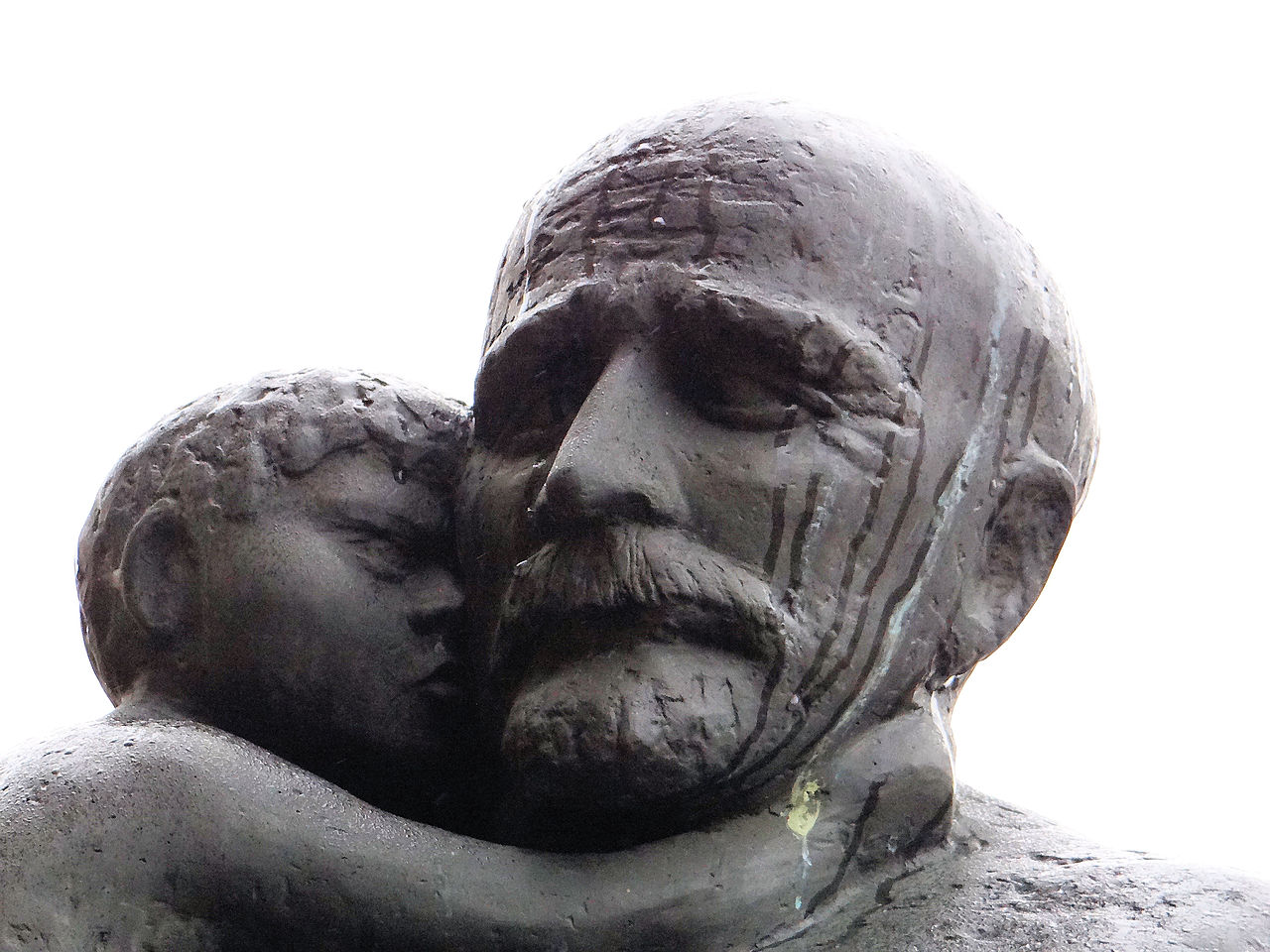

Polish educator Janusz Korczak set out to remake the world just as it was falling apart. In the 1930s his Warsaw orphanage was an enlightened society run by the children themselves, but he struggled to keep that ideal alive as Europe descended into darkness. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll tell the story of the children’s champion and his sacrifices for the orphans he loved.

We’ll also visit an incoherent space station and puzzle over why one woman needs two cars.

When the Seneca Army Depot in upstate New York was shut down in 2000 it left an odd legacy: the world’s largest herd of white deer. The fence erected around the facility in 1941 happened to enclose a few white-tailed deer that carried a recessive gene for all-white coats; the depot commander forbade his GIs to shoot any white deer, and eventually the white herd grew to number more than 300.

These are not albinos; they have brown eyes, not pink, and they live alongside some 600 brown white-tailed deer. In 2016 the Army sold the depot to a local businessman, and part of the land has now been established as a conservation park. Bus tours have “turned out to be hugely successful.”