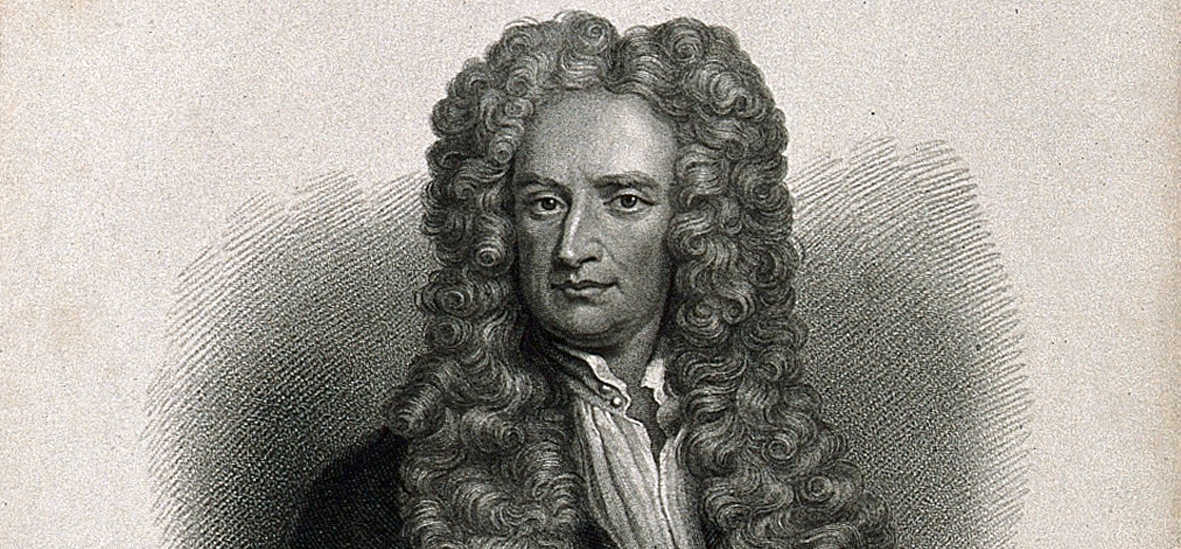

In 1662, while a student at Cambridge, 19-year-old Isaac Newton made a list of 57 sins he’d committed:

Before Whitsunday 1662

Using the word (God) openly

Eating an apple at Thy house

Making a feather while on Thy day

Denying that I made it.

Making a mousetrap on Thy day

Contriving of the chimes on Thy day

Squirting water on Thy day

Making pies on Sunday night

Swimming in a kimnel on Thy day

Putting a pin in Iohn Keys hat on Thy day to pick him.

Carelessly hearing and committing many sermons

Refusing to go to the close at my mothers command.

Threatning my father and mother Smith to burne them and the house over them

Wishing death and hoping it to some

Striking many

Having uncleane thoughts words and actions and dreamese.

Stealing cherry cobs from Eduard Storer

Denying that I did so

Denying a crossbow to my mother and grandmother though I knew of it

Setting my heart on money learning pleasure more than Thee

A relapse

A relapse

A breaking again of my covenant renued in the Lords Supper.

Punching my sister

Robbing my mothers box of plums and sugar

Calling Dorothy Rose a jade

Glutiny in my sickness.

Peevishness with my mother.

With my sister.

Falling out with the servants

Divers commissions of alle my duties

Idle discourse on Thy day and at other times

Not turning nearer to Thee for my affections

Not living according to my belief

Not loving Thee for Thy self

Not loving Thee for Thy goodness to us

Not desiring Thy ordinances

Not [longing] for Thee in [illegible]

Fearing man above Thee

Using unlawful means to bring us out of distresses

Caring for worldly things more than God

Not craving a blessing from God on our honest endeavors.

Missing chapel.

Beating Arthur Storer.

Peevishness at Master Clarks for a piece of bread and butter.

Striving to cheat with a brass halfe crowne.

Twisting a cord on Sunday morning

Reading the history of the Christian champions on Sunday

Since Whitsunday 1662

Glutony

Glutony

Using Wilfords towel to spare my own

Negligence at the chapel.

Sermons at Saint Marys (4)

Lying about a louse

Denying my chamberfellow of the knowledge of him that took him for a [illegible] sot.

Neglecting to pray 3

Helping Pettit to make his water watch at 12 of the clock on Saturday night

“We aren’t sure what prompted this confession,” writes Mitch Stokes in his 2010 biography of the physicist. “Some biographers think that it was in response to an inner crisis. Perhaps it was the occasion of his conversion, or at least of his ‘owning his faith.’ We simply don’t know.”