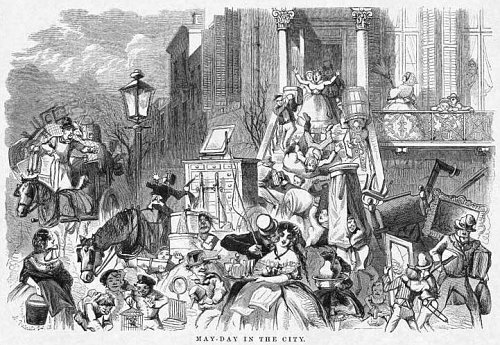

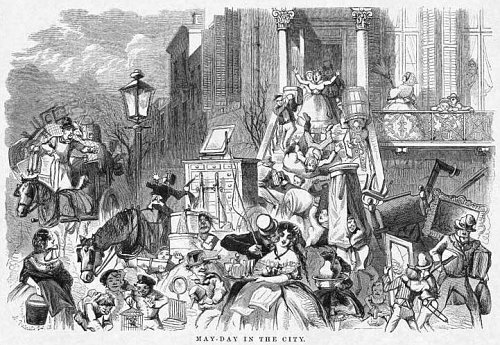

Changing apartments in New York City is an ordeal today, but it’s a great improvement over the old system, when every lease in the city expired at 9 a.m. on May 1 and thousands of people moved to new lodgings simultaneously. Davy Crockett witnessed the spectacle during a visit in 1834:

By the time we returned down Broadway, it seemed to me that the city was flying before some awful calamity. ‘Why,’ said I, ‘Colonel, what under heaven is the matter? Everyone appears to be pitching out their furniture, and packing it off.’ He laughed, and said this was the general ‘moving day.’ Such a sight nobody ever saw unless it was in this same city. It seemed a kind of frolic, as if they were changing houses just for fun. Every street was crowded with carts, drays, and people. So the world goes. It would take a good deal to get me out of my log-house; but here, I understand, many persons ‘move’ every year.

The tradition ran from colonial times until World War II, when a shortage of men finally ended it. That’s more than a century, an oddly long run for such an unpopular practice. “There may be some doubt as to whether landlords make out leases to suit the habits of the people, or whether the habits are a result of the leases,” journalist Luke Grant wrote in 1909, “but there is no doubt that the custom imposes hardships on every one concerned.”