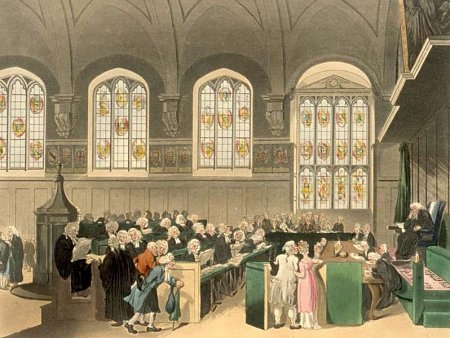

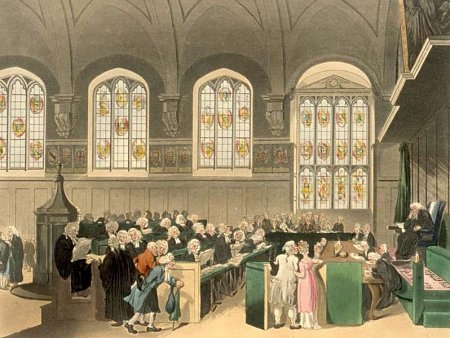

In England’s Court of Chancery, a litigant’s charges were converted into “interrogatories,” or searching questions to be put to the defendant, who had to answer them under oath. For example:

“Whether or no was the said testator, G. H., at the time of his death indebted to any and what persons or person in any and what sums or sum of money?”

Composing these questions was such mournfully mechanical work that a thoughtless clerk could turn almost anything into an interrogatory. Junior counsel Edward Karslake once submitted a rather florid account of a broken trust, and the clerk absently returned this:

“Did not the defendant fall down on her knees or on one and which of them and implore the plaintiff with tears in her eyes or in one and which of them to advance the said sum of £—- to her husband to save him from bankruptcy and their children from ruin or how otherwise?”

According to one story, a junior counsel wagered that if the first few lines of Paradise Lost were inserted into a bill, his clerk would render them into interrogatories “without turning a hair.” Here’s Milton’s text:

Of Man’s First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal taste

Brought Death into the World, and all our woe …

And here’s what the clerk produced:

“Was it man’s first or some other and what disobedience, and the fruit of that forbidden or some other and what tree, whose mortal taste brought death into this or some other and what world and all our woe, and if not why not or how otherwise?”

It was this tedious officiousness that Dickens railed about in Bleak House. He had some justice: The novel’s central case was inspired by a Chancery suit that took 36 years to get through court.