More proof that math is broken:

0 = 0 + 0 + 0 + …

0 = (1 – 1) + (1 – 1) + (1 – 1) + …

Okay so far? Now shift the parentheses:

0 = 1 + (-1 + 1) + (-1 + 1) + (-1 + 1) + …

0 = 1 + 0 + 0 + 0 + …

0 = 1

Now we’ll have to scrap the whole discipline.

More proof that math is broken:

0 = 0 + 0 + 0 + …

0 = (1 – 1) + (1 – 1) + (1 – 1) + …

Okay so far? Now shift the parentheses:

0 = 1 + (-1 + 1) + (-1 + 1) + (-1 + 1) + …

0 = 1 + 0 + 0 + 0 + …

0 = 1

Now we’ll have to scrap the whole discipline.

Only six numbers have this curious property:

1 = 1; 13 = 1

8 = 5 + 1 + 2; 83 = 512

17 = 4 + 9 + 1 + 3; 173 = 4913

18 = 5 + 8 + 3 + 2; 183 = 5832

26 = 1 + 7 + 5 + 7 + 6; 263 = 17576

27 = 1 + 9 + 6 + 8 + 3; 273 = 19683

They’re called Dudeney numbers, after the English author and mathematician who discovered them. (Regular readers know I’m something of a fan.)

Isaac Asimov proposed a simple way to distinguish chemists from non-chemists: Ask them to read aloud the word unionized.

Non-chemists will pronounce it “union-ized”, he said — and chemists will pronounce it “un-ionized.”

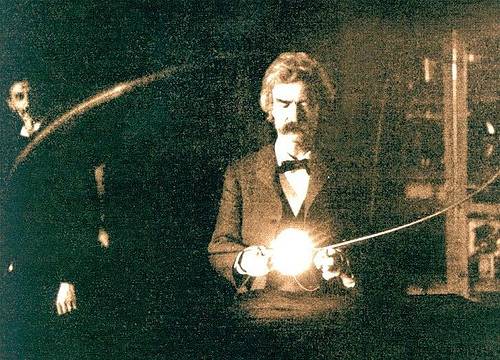

Mark Twain in the laboratory of his friend, inventor Nikola Tesla, where in 1894 Twain briefly became a human light bulb:

In Fig. 13 a most curious and weird phenomenon is illustrated. A few years ago electricians would have considered it quite remarkable, if indeed they do not now. The observer holds a loop of bare wire in his hands. The currents induced in the loop by means of the “resonating” coil over which it is held, traverse the body of the observer, and at the same time, as they pass between his bare hands, they bring two or three lamps held there to bright incandescence. Strange as it may seem, these currents, of a voltage one or two hundred times as high as that employed in electrocution, do not inconvenience the experimenter in the slightest. The extremely high tension of the currents which Mr. Clemens is seen receiving prevents them from doing any harm to him.

— T.C. Martin, “Tesla’s Oscillator and Other Inventions,” Century Magazine, April 1895

Every issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1947 has displayed a clock face on its cover, symbolizing the world’s proximity to nuclear war (in the judgment of the bulletin’s board of directors).

At its most dire, the clock stood at two minutes to midnight in 1953, when the United States and the Soviet Union tested thermonuclear devices within nine months of one another. Thirty-eight years later, when the superpowers signed the START treaty in 1991, the clock reached 17 minutes to midnight, its most hopeful position to date.

That doesn’t mean we’re making progress. Today it stands at 7 minutes to midnight — which is just where it started 59 years ago.

0.999… is the same as 1. Not just very close, but precisely identical:

a = 0.999…

10a = 9.999…

10a – a = 9.999… – 0.999…

9a = 9

a = 1

There’s no trick here. It’s just a mathematical fact that most people find deeply counterintuitive.

In English, every odd number contains the letter e.

Between the 762nd and 767th decimal places of pi there are six 9s in a row.

It’s called the Feynman point, because physicist Richard Feynman said he’d like to recite 761 digits and end with “… nine, nine, nine, nine, nine, nine, and so on.”

32 + 42 = 52

And:

33 + 43 + 53 = 63

2646798 = 21 + 62 + 43 + 64 + 75 + 96 + 87