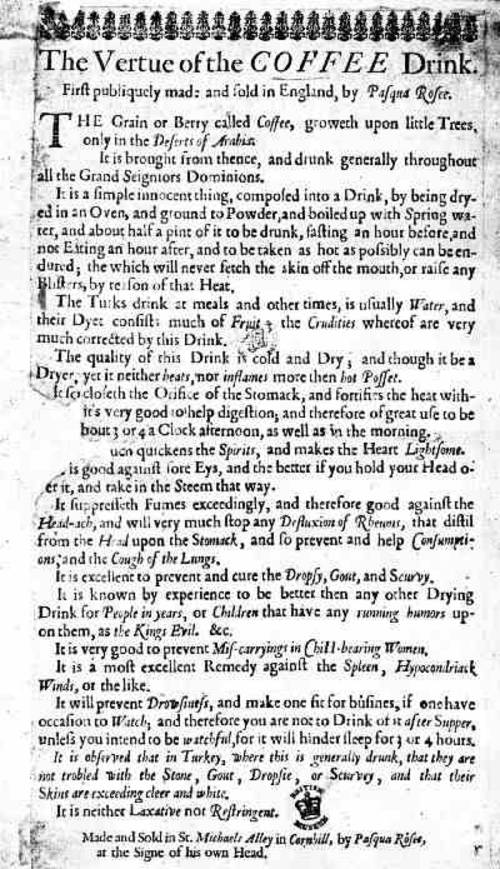

In the 1650s an intriguing handbill appeared in London:

A merchant named Dan Edwards had brought the first coffee to England in 1652, and his Greek servant, Pasqua Rosee, opened the first coffee-house there. Evidently he saw some potential.

In the 1650s an intriguing handbill appeared in London:

A merchant named Dan Edwards had brought the first coffee to England in 1652, and his Greek servant, Pasqua Rosee, opened the first coffee-house there. Evidently he saw some potential.

Besieged in Stalingrad during the bitter winter of 1943, the German 6th Army sent home one last post before surrendering in February to the encircling Red Army. An excerpt from one anonymous letter:

It’s strange that one does not start to value things until one is about to lose them. There is a bridge from my heart to yours, spanning all the vastness of distance. Across that bridge I have been used to writing to you about our daily round and the world we live in out here. I wanted to tell you the truth when I came home, and then we would never have spoken of war again. Now you will learn the truth, the last truth, earlier than I intended. And now I can write no more.

There will always be bridges as long as there are shores; all we need is the courage to tread them. One of them now leads to you, the other into eternity — which for me is ultimately the same thing.

Tomorrow morning I shall set foot on the last bridge. That’s a literary way of describing death, but you know I always liked to write things differently because of the pleasure words and their sounds gave me. Lend me your hand, so that the way is not too hard.

It was never delivered. Hitler ordered the letters analyzed to learn the state of army morale. The Wehrmacht reported that 2.1 percent of the letters approved of the conduct of the war, 3.4 percent were vengefully opposed, 57.1 percent were skeptical and negative, 33 percent were indifferent, and 4.4 percent were doubtful.

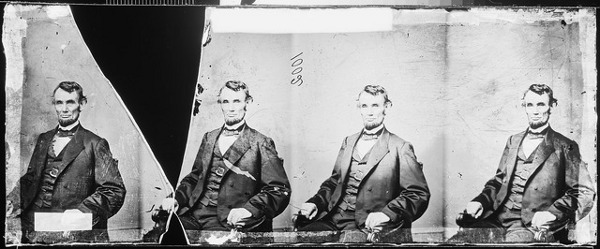

In 1908, while traveling in the northern Caucasus, Leo Tolstoy regaled a local tribe with tales of the greatest warriors and statesmen in history. When he had finished, the chief said, “But you have not told us a syllable about the greatest general and greatest ruler of the world. We want to know something about him. He was a hero. He spoke with a voice of thunder; he laughed like the sunrise, and his deeds were strong as the rock and as sweet as the fragrance of roses. The angels appeared to his mother and predicted that the son whom she would conceive would become the greatest the stars had ever seen. He was so great that he even forgave the crimes of his greatest enemies and shook brotherly hands with those who had plotted against his life. His name was Lincoln and the country in which he lived is called America, which is so far away that if a youth should journey to reach it he would be an old man when he arrived. Tell us of that man.”

“I looked at them,” Tolstoy recalled, “and saw their faces all aglow, while their eyes were burning. I saw that those rude barbarians were really interested in a man whose name and deeds had already become a legend.”

Tolstoy reflected that this “little incident proves how largely the name of Lincoln is worshipped throughout the world and how legendary his personality has become. Now, why was Lincoln so great that he overshadows all other national heroes? … [H]is supremacy expresses itself altogether in his peculiar moral power and in the greatness of his character. He had come through many hardships and much experience to the realization that the greatest human achievement is love. He was what Beethoven was in music, Dante in poetry, Raphael in painting, and Christ in the philosophy of life. He aspired to be divine — and he was. It is natural that before he reached his goal he had to walk the highway of mistakes. But we find him, nevertheless, in every tendency true to one main motive, and that was to benefit mankind. He was one who wanted to be great through his smallness. If he had failed to become President he would be, no doubt, just as great as he is now, but only God would appreciate it. The judgment of the world is usually wrong in the beginning, and it takes centuries to correct it. But in the case of Lincoln the world was right from the start.”

Letter to the Times, March 10, 1950:

Sir,

I should like to place on record that at my son’s baptism today there was present one lady whose father, born in 1794, had fought under Wellington in the Peninsular War.

If this boy or others of my children live the allotted 70 years they will be able to claim to be among the very few people who in 2020 will say: ‘I had a friend once who told me how cross her father had been at the postal delays when he was in Spain with Wellington 200 years ago.’

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

P.J.M. Rous

Astrologer William Lilly managed to torpedo his own reputation. Nettled at rumors abroad in London, he published this advertisement in the Perfect Diurnal of April 9, 1655:

Whereas there are several flying reports, and many false and scandalous speeches in the mouth of many people in this City, tending unto this effect, viz., that I, William Lilly, should predict or say there would be a great fire in or near the Old Exchange, and another in St. John’s Street, and another in the Strand, near Temple Bar, and in several other parts of the City. These are to certify the whole City that I protest before Almighty God that I never wrote any such thing, I never spoke any such word, or ever thought of any such thing, of any or all of these particular places or streets, or any other parts. These untruths are forged by ungodly men and women to disturb the quiet people of the City, to amaze the nation, and to cast aspersions and scandals on me.

He should have held his tongue — the Great Fire of London broke out on Sept. 2, 1666, and consumed more than 13,000 houses, fulfilling the prophecy that Lilly had disclaimed.

“He must have misread the stars,” wrote Walter George Bell in Fleet Street in Seven Centuries. “Not to have forecasted the fire would not have mattered; but to have prophesied that it would not take place! The fool! the abject, intolerable fool!”

Letter to the New York Times, March 26, 1911:

Dear Mr. Editer

i Went down town with my daddy yesterday to see that terrible fire where all the littel girls jumped out of high windows My littel cousin Beatrice and i are sending you five dollars a piece from our savings bank to help them out of trubble please give it to the right one to use it for sombody whose littel girl jumped out of a window i wouldent like to jump out of a high window myself.

Yours Truly,

Morris Butler

One day [A.J. Conant] asked Mr. Lincoln how he became interested in the law. ‘It was Blackstone’s “Commentaries” that did it,’ said Mr. Lincoln, and then he related how he first happened on the books. ‘I was keeping store in New Salem, when one day a man who was migrating to the West drove up with a wagon which contained his family and household plunder. He asked me if I would buy an old barrel for which he had no room in his wagon, and which he said contained nothing of special value. I did not want it, but to oblige him I bought it and paid him, I think, half a dollar. Without further examination I put it away in the store and forgot all about it. Sometime after, in overhauling things, I came upon the barrel and emptied its contents upon the floor. I found at the bottom of the rubbish a complete edition of Blackstone’s “Commentaries.” I began to read those famous works, and I had plenty of time, for during the long summer days, when the farmers were busy with their crops, my customers were few and far between. The more I read’ — this he said with unusual emphasis — ‘the more intensely interested I became. Never in my whole life was my mind so thoroughly absorbed. I read until I devoured them.’ …

— Ida M. Tarbell, Selections From the Letters, Speeches, and State Papers of Abraham Lincoln, 1911

Letter to the Times from the Dean of Canterbury, Feb. 5, 1970:

Sir,

A few days ago I received a communication addressed to T.A. Becket, Esq., care of The Dean of Canterbury. This surely must be a record in postal delays.

Yours truly,

Ian H. White-Thomson

Abraham Lincoln’s former law partner, William Henry Herndon, published a biography of the president in 1889. While gathering material for the project, he received this letter from a colleague:

Dear Herndon:

One morning, not long before Lincoln’s nomination — a year perhaps — I was in your office and heard the following: Mr. Lincoln, seated at the baize-covered table in the center of the office, listened attentively to a man who talked earnestly and in a low tone. After being thus engaged for some time Lincoln at length broke in, and I shall never forget his reply. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘we can doubtless gain your case for you; we can set a whole neighborhood at loggerheads; we can distress a widowed mother and her six fatherless children and thereby get for you six hundred dollars to which you seem to have a legal claim, but which rightfully belongs, it appears to me, as much to the woman and her children as it does to you. You must remember that some things legally right are not morally right. We shall not take your case, but will give you a little advice for which we will charge you nothing. You seem to be a sprightly, energetic man; we would advise you to try your hand at making six hundred dollars in some other way.’

Yours,

Lord

One day I was out milking the cows. Mr. Dave come down into the field, and he had a paper in his hand. ‘Listen to me, Tom,’ he said, ‘listen to what I reads you.’ And he read from a paper all about how I was free. You can’t tell how I felt. ‘You’re jokin’ me.’ I says. ‘No, I ain’t,’ says he. ‘You’re free.’ ‘No,’ says I, ‘it’s a joke.’ ‘No,’ says he, ‘it’s a law that I got to read this paper to you. Now listen while I read it again.’

But still I wouldn’t believe him. ‘Just go up to the house,’ says he, ‘and ask Mrs. Robinson. She’ll tell you.’ So I went. ‘It’s a joke,’ I says to her. ‘Did you ever know your master to tell you a lie?’ she says. ‘No,’ says I, ‘I ain’t.’ ‘Well,’ she says, ‘the war’s over and you’re free.’

By that time I thought maybe she was telling me what was right. ‘Miss Robinson,’ says I, ‘can I go over to see the Smiths?’ — they was a colored family that lived nearby. ‘Don’t you understand,’ says she, ‘you’re free. You don’t have to ask me what you can do. Run along, child.’

And so I went. And do you know why I was a-going? I wanted to find out if they was free too. I just couldn’t take it all in. I couldn’t believe we was all free alike.

Was I happy? Law, miss. You can take anything. No matter how good you treat it — it wants to be free. You can treat it good and feed it good and give it everything it seems to want — but if you open the cage — it’s happy.

— Former slave Tom Robinson, 88, of Hot Springs, Ark., interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project for the Slave Narrative Collection of 1936-38