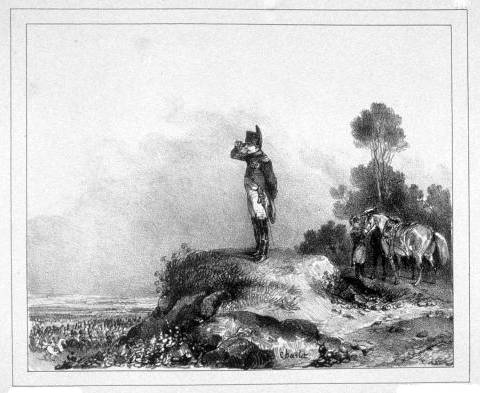

Bonaparte: Alone I am in this sequestered spot, not overheard.

Echo: Heard.

Bonaparte: ‘Sdeath! Who answers me? What being is there nigh?

Echo: I.

Bonaparte: Now I guess! To report my accents Echo has made her task.

Echo: Ask.

Bonaparte: Knowest thou whether London will henceforth continue to resist?

Echo: Resist.

Bonaparte: Whether Vienna and other courts will oppose me always?

Echo: Always.

Bonaparte: O, Heaven! what must I expect after so many reverses?

Echo: Reverses.

Bonaparte: What! should I, like a coward vile, to compound be reduced?

Echo: Reduced.

Bonaparte: After so many bright exploits be forced to restitution?

Echo: Restitution.

Bonaparte: Restitution of what I’ve got by true heroic feats and martial address?

Echo: Yes.

Bonaparte: What will be the fate of so much toil and trouble?

Echo: Trouble.

Bonaparte: What will become of my people, already too unhappy?

Echo: Happy.

Bonaparte: What should I then be that I think myself immortal?

Echo: Mortal.

Bonaparte: The whole world is filled with the glory of my name, you know.

Echo: No.

Bonaparte: Formerly its fame struck this vast globe with terror.

Echo: Error.

Bonaparte: Sad Echo, begone! I grow infuriate! I die!

Echo: Die!

It’s said that the Nuremberg bookseller who penned this clever bit of sedition was court-martialed and shot in 1807. Napoleon later said, “I believe he met with a fair trial.”