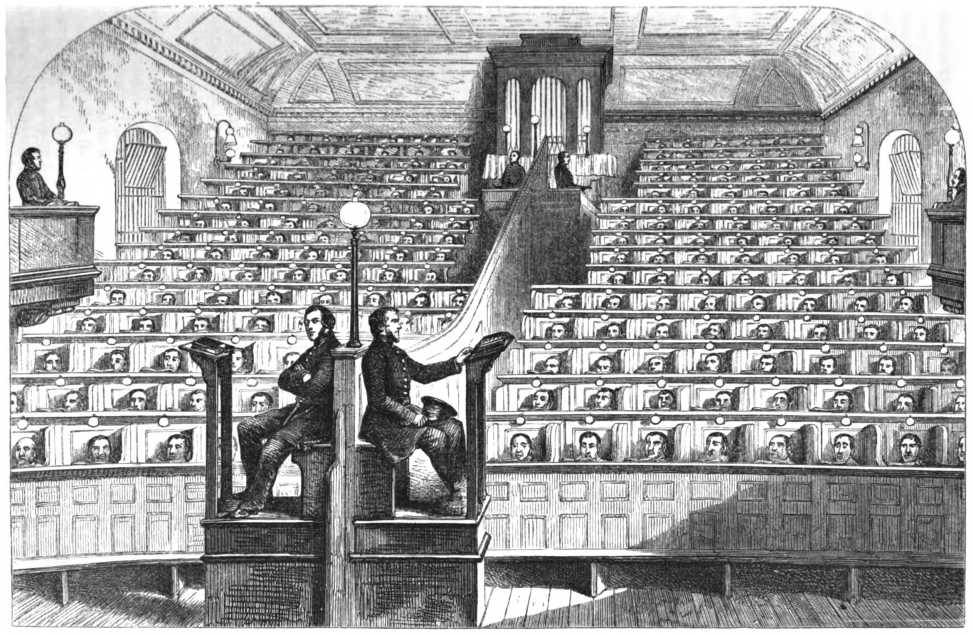

Until the 1990s it was arguably legal to purchase stolen goods in London’s Bermondsey Market without fear of prosecution.

The market operated under the ancient law of marché ouvert, or “open market,” a medieval legal concept that allowed for the open sale of stolen goods between the sunset and sunrise in designated markets in a city.

The idea was that if you were robbed and you didn’t check to see whether your stolen property was being sold in a local market, then you weren’t taking reasonable steps to recover it.

Surprisingly, Bermondsey Market operated under this law until 1995, when a stolen Joshua Reynolds painting was sold there for 100 pounds and the purchaser avoided prosecution for handling stolen goods by arguing that the sale was subject to these rules. The loophole has since been abolished.

(Thanks, Cathy.)

05/01/2019 UPDATE: A better explanation: It was never legal to sell or buy stolen goods knowingly. Ordinarily if a buyer is convicted of handling stolen goods then a court can order the goods returned to the original owner, and even without a criminal prosecution the owner can still seek recovery of their goods by appealing to a principle of the common law known as “nemo dat quod non habet” (“no one may give what he does not have”) — even if a buyer pays a fair price for goods she doesn’t know are stolen, she can’t obtain “good title,” ownership that defeats the claims of others, so the original owner can still recover the goods. “Market overt” is an exception to the nemo dat rule — until 1995, anything bought in good faith at a market overt in England became the legal property of the buyer, including title, even if it turned out to have been stolen — the original owner had no legal redress.

Market overt regulations were regarded as a valuable form of consumer protection when they were instantiated in the 12th century, but by the end of the 20th they had become known as the “thieves’ charter” for the dodgy sales they permitted. “It is a good thing it’s been stopped,” one Bermondsey trader told the Guardian in 1995. “People knew that market overt gave them a licence to bring stolen stock down here once a week.”

(Thanks, David.)