Introduced in the early 1800s, the “separate system” of prison architecture kept prisoners isolated from one another, to make them easier to control and to destroy the criminal subculture that could otherwise arise in dense populations. Prisoners were reduced to numbers, without names or histories, and the guards were forbidden to speak to them; in the exercise yard they tramped silently in rows, their faces hidden by brown cloth masks.

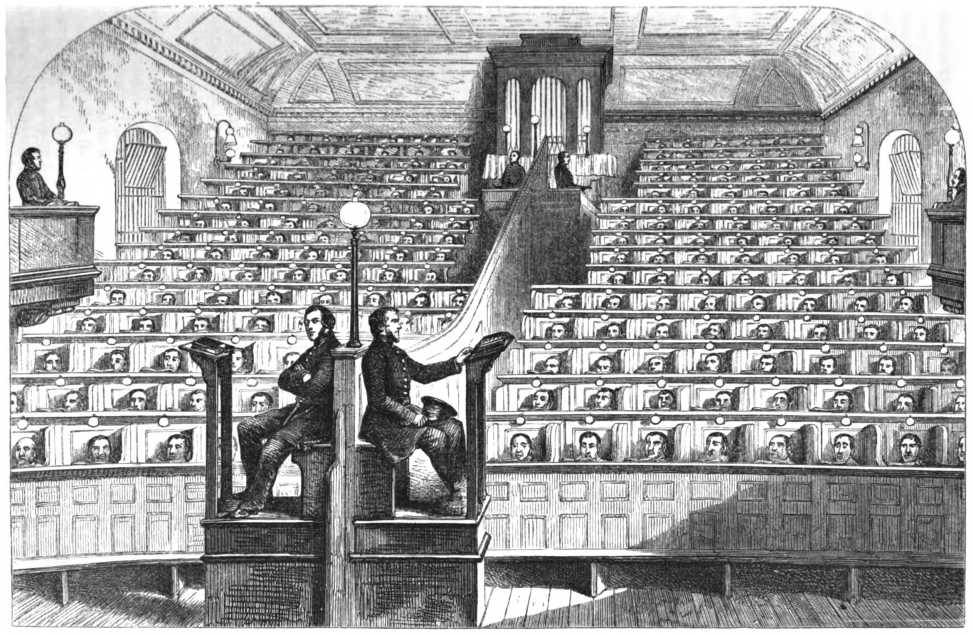

At London’s Pentonville prison this separation extended even to the chapel, where the assembled prisoners could see the chaplain but not each other. “Every man, as he enters, knows the precise row and seat that he has to occupy, and though some few pass in together at the same moment, these go to opposite quarters of the gallery,” observed journalist Henry Mayhew. “Each convict is able to get to his seat, and to close the partition-door of his stall after him, before the one following his steps has time to enter the same row.”

After the service, their exit was managed by a curious mechanical device that displayed each stall number in succession. “Thus the chapel is entirely emptied, not only with considerable rapidity, but without any disturbance or confusion.”

Pentonville was considered a model British prison of its time, and some 300 prisons worldwide were eventually built on the separate system. But an official report acknowledged that “for every sixty thousand persons imprisoned in Pentonville there were 220 cases of insanity, 210 cases of delusion, and forty suicides.”

(Henry Mayhew, The Criminal Prisons of London, 1862.)