Edmund Kean was accounted the greatest actor of his generation, but not everyone shared that opinion. Violette Garrick wrote to him:

You don’t know how to play Abel Drugger.

He wrote back:

I know it.

Edmund Kean was accounted the greatest actor of his generation, but not everyone shared that opinion. Violette Garrick wrote to him:

You don’t know how to play Abel Drugger.

He wrote back:

I know it.

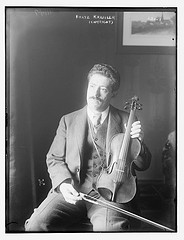

Fritz Kreisler had already gained immortality as a violin virtuoso when in 1935 he revealed that he was also a composer — for 30 years he had been performing his own compositions in concert but attributing them to Vivaldi, Couperin, Porpora, and Pugnani.

In the uproar that followed, Kreisler argued that as a young man he’d had no reputation; audiences would not have paid to hear the compositions of an unknown violinist. That was just the point, opined the Philadelphia Record: Fans had bought the pieces, and indeed other violinists had performed them, thinking them the work of established composers.

The Portland Oregonian agreed: “What if Fritz Kreisler had died without making confession that over a period of thirty years he had been composing music and signing to it the names of half-forgotten composers of former times? What if he had left no list of his works?”

Which raises an interesting question: How many such hoaxes have succeeded? How many of our great works of art are undiscovered forgeries?

That’s a caricature of Arturo Toscanini by Enrico Caruso.

There are many tales of the conductor’s astonishing musical memory. A clarinetist once approached him just before a performance and said that he would be unable to play because the E-natural key on his instrument was broken.

Toscanini concentrated for a short time and said, “It’s all right. You don’t have an E natural tonight.”

As part of a modern dance program, Paul Taylor once stood motionless on stage for four minutes.

For its review, Dance Observer magazine ran four inches of white space.

“Debussy’s music is the dreariest kind of rubbish. Does anybody for a moment doubt that Debussy would write such chaotic, meaningless, cacophonous, ungrammatical stuff, if he could invent a melody?” — New York Post, 1907

“It is probable that much, if not most, of Stravinsky’s music will enjoy brief existence.” — New York Sun, Jan. 16, 1937

“Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, like the first pancake, is a flop.” — Nicolai Soloviev, Novoye Vremya, St. Petersburg, Nov. 13, 1875

“Rigoletto is the weakest work of Verdi. It lacks melody.” — Gazette Musicale de Paris, May 22, 1853

“Sure-fire rubbish.” — New York Herald Tribune on Porgy and Bess, Oct. 11, 1935

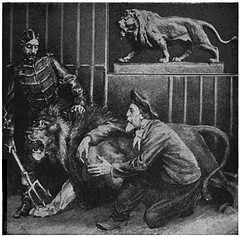

French sculptor Louis Vidal was blind since youth, but he produced startlingly faithful renderings of animals: a bull, a wounded stag, a horse, a cow, a dog.

With domestic creatures he could do this by feeling their anatomy directly, or by referring to skeletons or to stuffed specimens. But how did he create The Roaring Lion, the masterpiece first shown at the Salon in 1868?

Legend has it that he did it the hard way: by running his hands over a live lion at the Jardin des Plantes.

“Convinced he would not succeed without having recourse to the living ‘king of beasts,'” reported The English Illustrated Magazine in 1900, “he entered the cage without the least hesitation, accompanied by the lion-tamer. The animal allowed itself to be caressed for some time, and Vidal was thus enabled to study its anatomy. As a result, he produced that most wonderful example of his art, ‘The Roaring Lion.'”

If that’s just a story … then how did he manage it?

Excerpts from concert reviews in London’s Harmonicon:

June 1823:

Opinions are much divided concerning the merits of the Pastoral symphony of Beethoven, though very few venture to deny that it is much too long.

July 1825:

[Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony] is a composition in which the author has indulged a great deal of disagreeable eccentricity. Often as we now have heard it performed, we cannot yet discover any design in it, neither can we trace any connexion in its parts. Altogether it seems to have been intended as a kind of enigma — we had almost said a hoax.

June 1827:

[Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony] depends wholly on its last movement for what applause it obtains; the rest is eccentric without being amusing, and laborious without effect.

April 1825:

We now find [the length of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony] to be precisely one hour and five minutes; a fearful period indeed, which puts the muscles and lungs of the band, and the patience of the audience to a severe trial.

“But how did you get to understand Beethoven?” wrote John Ruskin to John Brown in 1881. “He always sounds to me like the upsetting of bags of nails, with here and there an also dropped hammer.”

Here’s some pretty abstract expressionism — it was painted by a dog. Tillamook Cheddar is a Jack Russell terrier who works with her claws and teeth, spending hours on each canvas and biting anyone who interferes.

She knows what she’s doing — to date she’s had 16 exhibitions in the United States, Bermuda, the Netherlands, and Belgium, and earned $100,000.

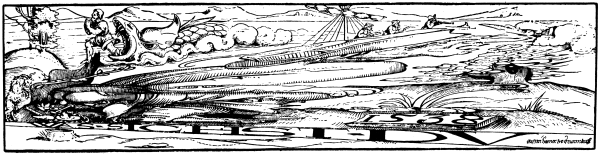

We met Erhard Schön’s anamorphic woodcuts back in 2006.

This one, Was sichst du? (What Do You See?), from 1538, seems to promise an edifying religious theme — there’s Jonah on the left being spit out of his whale. But view it edge-on and you’ll see this:

So, maybe not.

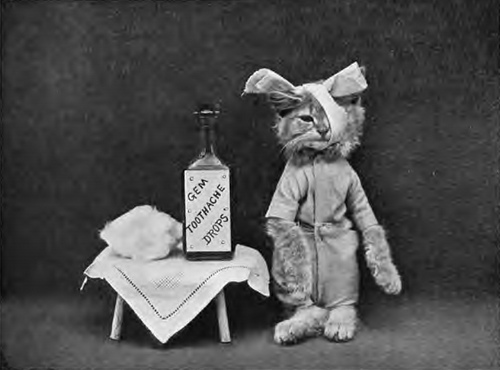

Harry Whittier Frees did a booming business in novelty postcards in the early 20th century, posing animals in human situations, including props and sets.

“I take occasion to give my personal assurance that all pictures appearing in this book are photographed from life,” he wrote in 1915’s The Little Folks of Animal Land. “The difficulties encountered in posing kittens and puppies for pictures of this kind have been overcome only by the exercise of great patience and invariable kindness.”