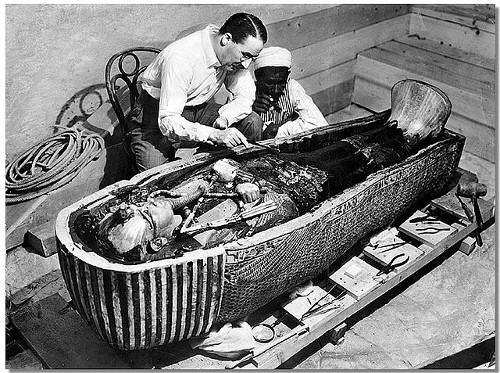

Letter from the Bishop of Chelmsford to the Times, Feb. 3, 1923:

Sir, I wonder how many of us, born and brought up in the Victorian era, would like to think that in the year, say, 5923, the tomb of Queen Victoria would be invaded by a party of foreigners who rifled it of its contents, took the body of the great Queen from the mausoleum in which it had been placed amid the grief of the whole people, and exhibited it to all and sundry who might wish to see it?

The question arises whether such treatment as we should count unseemly in the case of the great English Queen is not equally unseemly in the case of King Tutankhamen. I am not unmindful of the great historical value which may accrue from the examination of the collection of jewelry, furniture, and, above all, of papyri discovered within the tomb, and I realize that wide interests may justify their thorough investigation and even, in special cases, their temporary removal. But, in any case, I protest strongly against the removal of the body of the King from the place where it has rested for thousands of years. Such a removal borders on indecency, and traverses all Christian sentiment concerning the sacredness of the burial places of the dead.

J.E. Chelmsford