“The discovery of a new dish does more for human happiness than the discovery of a new star.” — Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

“The discovery of a new dish does more for human happiness than the discovery of a new star.” — Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

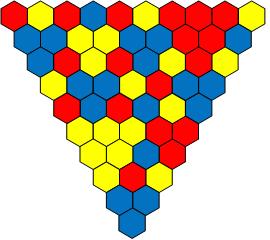

Make an inverted triangle of hexagonal cells with side length 3n + 1, and color the cells in the top row randomly in three colors. Now color the cells in the second row according to these rules:

When you’ve finished the second row, continue through the succeeding ones, applying the same rules. Pleasingly, no matter how large the triangle, the color of the last cell can be predicted at the start: Just apply our two guiding rules to the endmost cells in the top row. If those two cells are both red, the last cell will be red. If one is red and one is yellow (as in the figure above), the bottom cell will be blue.

The principle was discovered by Newcastle University mathematician Steve Humble in 2012. Gary Antonick gives more background here, and see the paper below for a mathematical discussion by Humble and Ehrhard Behrends.

(Ehrhard Behrends and Steve Humble, “Triangle Mysteries,” Mathematical Intelligencer 35:2 [June 2013], 10-15.)

George Orwell’s six rules of writing, from “Politics and the English Language,” 1946:

But “one could keep all of them and still write bad English.”

English novelist Winifred Ashton had a disastrous gift for inadvertent double entendre. From Cole Lesley’s biography of Noël Coward:

The first I can remember was when poor Gladys was made by Noël to explain to Winifred that she simply could not say in her latest novel, ‘He stretched out and grasped the other’s gnarled, stumpy tool.’ The Bloomers poured innocently from her like an ever-rolling stream: ‘Olwen’s got crabs!’ she cried as you arrived for dinner, or ‘We’re having roast cock tonight!’ At the Old Vic, in the crowded foyer, she argued in ringing tones, ‘But Joyce, it’s well known that Shakespeare sucked Bacon dry.’ It was Joyce too who anxiously inquired after some goldfish last seen in a pool in the blazing sun and was reassured, ‘Oh, they’re all right now! They’ve got a vast erection covered with everlasting pea!’ ‘Oh the pleasure of waking up to see a row of tits outside your window,’ she said to Binkie during a weekend at Knott’s Fosse. Schoolgirl slang sometimes came into it, for she was in fact the original from whom Noël created Madame Arcati: ‘Do you remember the night we all had Dick on toast?’ she inquired in front of the Governor of Jamaica and Lady Foot. Then there was her ghost story : ‘Night after night for weeks she tried to make him come …’

“Why could she not have used the word ‘materialise’?” wrote Lesley, who was Coward’s secretary. “But then if she had we should never have had the fun.” See Shocking!

I think I mentioned this on the podcast at some point: One summer morning in 1815, proprietor William Butterfield opened the White Wells at Ilkley, West Yorkshire, to a sound of whirring:

All over the water and dipping into it was a lot of little creatures, all dressed in green from head to foot, none of them more than eighteen inches high, and making a chatter and jabber thoroughly unintelligible. They seemed to be taking a bath, only they bathed with all their clothes on.

Soon, however, one or two of them began to make off, bounding over the walls like squirrels. Finding they were all making ready for decamping, and wanting to have a word with them, he shouted at the top of his voice — indeed, he declared afterwards, he couldn’t find anything else to say or do — ‘Hallo there!’ Then away the whole tribe went, helter skelter, toppling and tumbling, heads over heels, heels over heads, and all the while making a noise not unlike a disturbed nest of young partridges.

That’s the account recorded by Charles C. Smith in the Folk-Lore Record of 1878. Butterfield had died in 1844, but Smith had the story from his associate John Dobson, who described the bathman as “a good sort of a man, honest, truthful, and steady, and as respectable a fellow as you could find here and there.” The fairies made no comment.

Josiah Winslow’s programming language Bespoke encodes instructions into the lengths of words, producing programs that look like poetry. This one prints the phrase “Hello, World!”:

more peppermint tea? ah yes, it's not bad I appreciate peppermint tea it's a refreshing beverage but you immediately must try the gingerbread I had it sometime, forever ago oh, and it was so good! made the way a gingerbread must clearly be baked in fact, I've got a suggestion I may go outside to Marshal Mellow's Bakery so we both receive one

Related: In the early 1980s, Frank Hayes was so vexed with the S-100 computer bus that he wrote a sea shanty about it:

(Thanks, Jeremiah.)

Each side of the yellow square is 2 feet long. In the Meno, Socrates asks a slave boy how long would be the side of a square that had twice the yellow square’s area. The boy guesses first 4 feet, then 3, and finds himself at a loss.

Socrates builds a square four times the size of the yellow one, then divides each of its constituent squares in half with a diagonal. The area of the blue square is thus twice that of the yellow one, and its side has the length we’d sought.

“Some things I have said of which I am not altogether confident,” Socrates tells Meno. “But that we shall be better and braver and less helpless if we think that we ought to enquire, than we should have been if we indulged in the idle fancy that there was no knowing and no use in seeking to know what we do not know; that is a theme upon which I am ready to fight, in word and deed, to the utmost of my power.”

Another exercise in linguistic purism: In his 1989 essay “Uncleftish Beholding,” Poul Anderson tries to explain atomic theory using Germanic words almost exclusively, coining terms of his own as needed:

The firststuffs have their being as motes called unclefts. These are mightly small; one seedweight of waterstuff holds a tale of them like unto two followed by twenty-two naughts. Most unclefts link together to make what are called bulkbits. Thus, the waterstuff bulkbit bestands of two waterstuff unclefts, the sourstuff bulkbit of two sourstuff unclefts, and so on. (Some kinds, such as sunstuff, keep alone; others, such as iron, cling together in ices when in the fast standing; and there are yet more yokeways.) When unlike clefts link in a bulkbit, they make bindings. Thus, water is a binding of two waterstuff unclefts with one sourstuff uncleft, while a bulkbit of one of the forestuffs making up flesh may have a thousand thousand or more unclefts of these two firststuffs together with coalstuff and chokestuff.

Reader Justin Hilyard, who let me know about this, adds, “This sort of not-quite-conlang is still indulged in now and then today; it’s often known as ‘Anglish’, after a coining by British humorist Paul Jennings in 1966, in a three-part series in Punch magazine celebrating the 900th anniversary of the Norman conquest. He also wrote some passages directly inspired by William Barnes in that same Germanic-only style.”

Somewhat related: In 1936 Buckminster Fuller explained Einstein’s theory of relativity in a 264-word telegram.

(Thanks, Justin.)

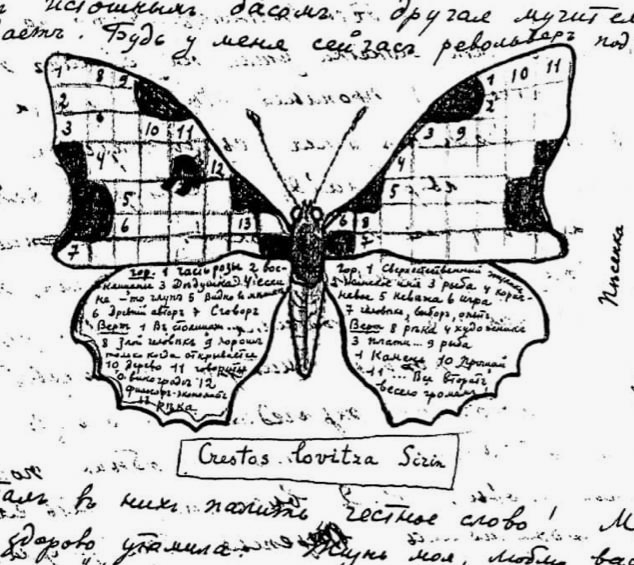

Vladimir Nabokov composed this puzzle for his wife Véra in 1926. The title, “Crestos lovitxa Sirin,” roughly means “Nabokov’s crossword”: krestlovitska approximates the Russian kreslovitsa, “cross” plus “words”, and Sirin is a pseudonym Nabokov often used, a reference to the creatures of Russian mythology. The upper half of each wing contains the grid, the lower the clues.

Nabokov, a trained entomologist, had published the first crossword in Russian two years earlier. Forty years later, in the Paris Review, he likened writing a novel to creating a crossword: “The pattern of the thing precedes the thing. I fill in the gaps of the crossword at any spot I happen to choose.”

(Adrienne Raphel, The Crossword Mentality in Modern Literature and Culture, dissertation, Harvard University, 2018.)

In 1988, traversing synonyms in the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary, A. Ross Eckler found his way from TRUE to FALSE:

TRUE-JUST-FAIR-BEAUTIFUL-PRETTY-ARTFUL-ARTIFICIAL-SHAM-FALSE

He found his way back again by a different route:

FALSE-UNWISE-FOOLISH-SIMPLE-UNCONDITIONAL-ABSOLUTE-POSITIVE-REAL-GENUINE-TRUE

He was using the dictionary’s ninth edition; see the article below for his conventions regarding qualifying synonyms. Two more examples:

BAD-POOR-MEAN-PENURIOUS-STINGY-CLOSE-SECRET-FURTIVE-SLY-CUNNING-CLEVER-GOOD

GOOD-CLEVER-CUNNING-SLY-FURTIVE-SECRET-TICKLISH-CRITICAL-ACUTE-SHARP-HARSH-ROUGH-INDELICATE-INDECOROUS-IMPROPER-INCORRECT-WRONG-SINFUL-WICKED-EVIL-BAD

LIGHT-BRIGHT-CLEVER-CUNNING-SLY-FURTIVE-SECRET-HIDDEN-OBSCURE-DARK

DARK-OBSCURE-VAGUE-VACANT-EMPTY-FOOLISH-SIMPLE-EASY-LIGHT

Somewhat related: Lewis Carroll invented word ladders, in which one transforms one word into another by changing one letter at a time:

COLD-CORD-WORD-WARD-WARM

Each intermediate step must itself be an English word. Donald Knuth once used a computer to find links among 5,757 common five-letter English words. 671 of these, he found, were not connected to any other word in the collection. These he dubbed “aloof” — and noted that ALOOF itself is such a word.

(A. Ross Eckler, “Websterian Synonym Chains,” Word Ways 21:2 [May 1988], 100-101.)