“To read History is to run the risk of asking, ‘Which is more honorable? To rule over people, or to be hanged?'” — J.G. Seume

“To read History is to run the risk of asking, ‘Which is more honorable? To rule over people, or to be hanged?'” — J.G. Seume

In Ambrosia and Small Beer (1964), Edward Marsh describes a way of passing time during a long sermon:

[Y]ou look out for words beginning with each letter of the alphabet in succession, and if you get as far as Z (for which you may count a Z in the middle of a word) you cast a Bible on the ground and leave the building. It is palpitating. On this occasion we were held up by B, which seemed as if it would never come; and as the sermon was short neither of us got beyond M.

In Strong Drink, Strong Language (1990), John Espey writes,

Like most ministers’ children, I imagine, I early perfected several techniques for surviving sermons — counting games, making knight’s moves through the congregation using bald heads, or brown-haired, or ladies’ hats for jumps; betting my right hand against my left on which side of the center aisle the next cough would come from; or what the division would be in the Lord’s Prayer between ‘debts’ and ‘trespasses.’ I had, after all, heard everything, and more than once, by the time I turned ten.

P.G. Wodehouse’s 1922 story “The Great Sermon Handicap” describes a variation on a horse race: “Steggles is making the book. Each parson is to be clocked by a reliable steward of the course, and the one that preaches the longest sermon wins.” In 1930 a group of Cambridge undergraduates carried this out in real life — the winner, for the record, was the Rev. H.C. Read, “riding” the parish church of St Andrew-the-Great.

In his 2007 history The Slave Ship, Marcus Rediker reports that sharks would sometimes follow slave ships entirely across the Atlantic, “that they might devour the bodies of the dead when thrown overboard,” in the words of veteran captain Hugh Crow. Observer Alexander Falconbridge wrote that sharks swarmed “in almost incredible numbers about the slave ships, devouring with great dispatch the dead bodies of the negroes.”

A notice published in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1785 reads, “The many Guineamen lately arrived here have introduced such a number of overgrown sharks, (The constant attendants on the vessels from the coasts) that bathing in the river is become extremely dangerous, even above town.”

In a natural history of sharks published in 1774, Oliver Goldsmith tells of a “rage for suicide” aboard one ship, whose captain made an example of one woman by lowering her into the water:

“When the poor creature was thus plunged in, and about half way down, she was heard to give a terrible shriek, which at first was ascribed to her fears of drowning; but soon after, the water appearing red all around her, she was drawn up, and it was found that a shark, which had followed the ship, had bit her off from the middle.”

When an editor complained that Gerald Kersh used too many long words, Kersh bet him £50 that he could write a story entirely in monosyllables. Kersh won:

We met on the stairs of Time: I was on my way up; he was on his way down. I was young; he was old, and poor — so poor that he did not know when luck would send him a meal and a bed.

Frederic Birmingham published the whole three-page story in his 1958 book The Writer’s Craft.

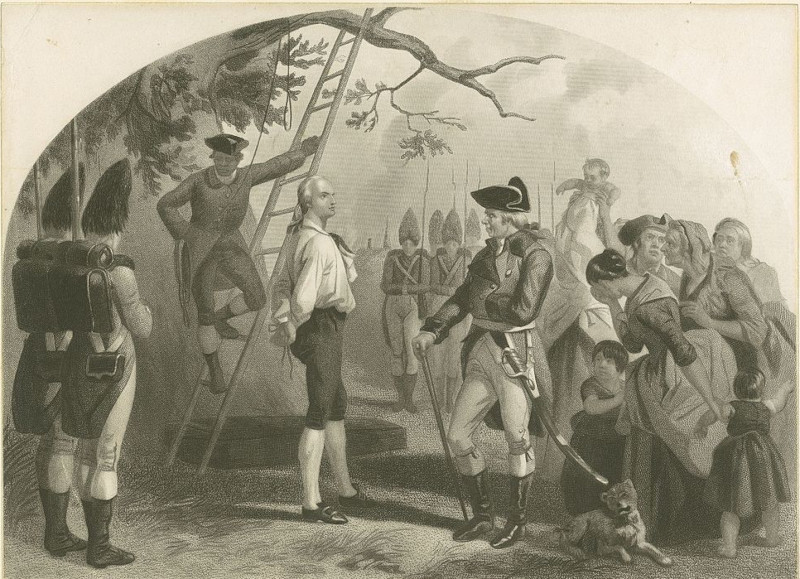

The infinite monkey theorem holds that a monkey typing at random for an infinite amount of time will almost certainly produce the works of Shakespeare.

This may be true, but mathematicians Stephen Woodcock and Jay Falletta of the University of Technology Sydney find that it would take an extraordinarily long time — longer, in fact, than the life span of the universe.

Assuming a typing speed of one character per second on a 30-key keyboard, they find, a single chimp has only about a 5 percent chance of typing BANANAS in its own lifetime. And even the entire global population of 200,000 chimps will almost certainly never string together the 884,647 words that make up Shakespeare’s works within 10100 years.

“There are many orders of magnitude difference between the expected numbers of keys to be randomly pressed before Shakespeare’s works are reproduced and the number of keystrokes until the universe collapses into thermodynamic equilibrium,” the authors conclude. “As such, we reject the conclusions from the Infinite Monkeys Theorem as potentially misleading within our finite universe.”

Speaking of Shakespeare: Grand Theft Hamlet is a British documentary about the staging of a production of Hamlet inside Grand Theft Auto:

Winner of the Jury Award for best documentary feature at the 2024 SXSW Film Festival, it will be released in the U.K. in December and globally early next year.

(Thanks, John.)

In the middle of winter when fogs and rains most abound they have a great festival which they call Exmas and for fifty days they prepare for it in the fashion I shall describe. First of all, every citizen is obliged to send to each of his friends and relations a square piece of hard paper stamped with a picture, which in their speech is called an Exmas-card. But the pictures represent birds sitting on branches, or trees with a dark green prickly leaf, or else men in such garments as the Niatirbians believe that their ancestors wore two hundred years ago riding in coaches such as their ancestors used, or houses with snow on their roofs. And the Niatirbians are unwilling to say what these pictures have to do with the festival; guarding (as I suppose) some sacred mystery. And because all men must send these cards the marketplace is filled with the crowd of those buying them, so that there is great labour and weariness.

But having bought as many as they suppose to be sufficient, they return to their houses and find there the like cards which others have sent to them. And when they find cards from any to whom they also have sent cards, they throw them away and give thanks to the gods that this labour at least is over for another year. But when they find cards from any to whom they have not sent, then they beat their breasts and wail and utter curses against the sender; and, having sufficiently lamented their misfortune, they put on their boots again and go out into the fog and rain and buy a card for him also. And let this account suffice about Exmas-cards.

— C.S. Lewis, “Xmas and Christmas: A Lost Chapter From Herodotus,” Time and Tide, Dec. 4, 1955

A pleasing little detail: In Arthur C. Clarke’s 1946 story “Rescue Party,” a federation of aliens visit Earth immediately before the sun explodes, hoping to rescue its inhabitants. To their surprise, they don’t find us (it turns out we’ve fled the planet), and they comb our deserted civilization.

The explorers were particularly puzzled by one room — clearly an office of some kind — that appeared to have been completely wrecked. The floor was littered with papers, the furniture had been smashed, and smoke was pouring through the broken windows from the fires outside.

T’sinadree was rather alarmed.

‘Surely no dangerous animal could have got into a place like this!’ he exclaimed, fingering his paralyzer nervously.

Alarkane did not answer. He began to make that annoying sound which his race called ‘laughter.’ It was several minutes before he would explain what had amused him.

‘I don’t think any animal has done it,’ he said. ‘In fact, the explanation is very simple. Suppose you had been working all your life in this room, dealing with endless papers, year after year. And suddenly, you are told that you will never see it again, that your work is finished, and that you can leave it forever. More than that — no one will come after you. Everything is finished. How would you make your exit, T’sinadree?’

The other thought for a moment.

‘Well, I suppose I’d just tidy things up and leave. That’s what seems to have happened in all the other rooms.’

Alarkane laughed again.

‘I’m quite sure you would. But some individuals have a different psychology. I think I should have liked the creature that used this room.’

No explanation is given. “His two colleagues puzzled over his words for quite a while before they gave it up.”

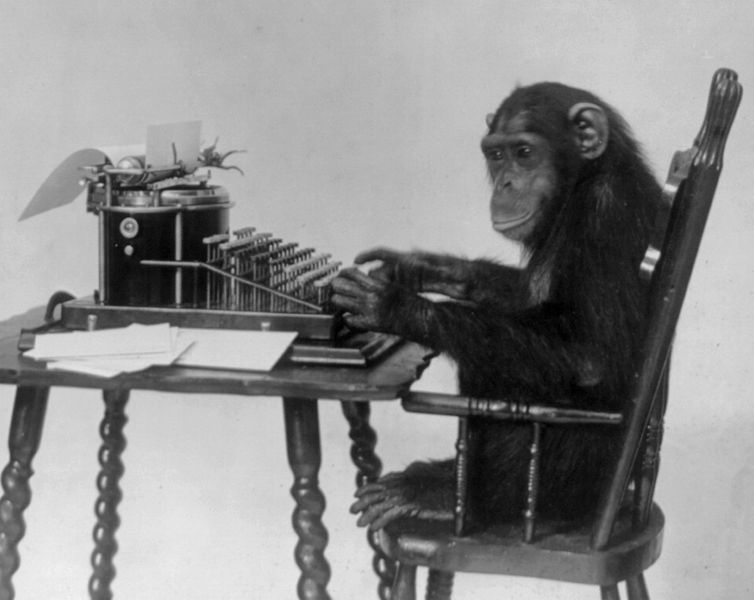

Francis Galton was interested in communicating with Mars as early as 1892, when he wrote a letter to the Times suggesting that we try flashing sun signals at the red planet. At a lecture the following year he described more specifically a method by which pictures might be encoded using 26 alphabetical characters, which could then be transmitted over a distance in 5-character “words,” in effect creating a low-resolution visual telegraph. As a study he reduced this profile of a Greek girl to 271 coded dots, which he found yielded “a very creditable production.”

This had huge implications, he felt. In 1896 he imagined a whole correspondence with a civilization of intelligent ants on Mars; in three and a half hours they catch our attention; teach us their base-8 mathematical notation; demonstrate their shared understanding of certain celestial bodies and mathematical constants; and finally propose a specified 24-gon in which points can be situated by code, like stitches in a piece of embroidery.

That opens a limitless avenue for colloquy — the Martians send images of Saturn, Earth, the solar system, and domestic and sociological drawings, a new one every evening. Galton concludes that two astronomical bodies that are close enough to signal one another with flashes of light already have everything they need to establish “an efficient inter-stellar language.”