Eunoia, by the Canadian poet Christian Bök, uses only one vowel per chapter:

Awkward grammar appals a craftsman. A Dada bard as daft as Tzara damns stagnant art and scrawls an alpha (a slapdash arc and a backward zag) that mars all stanzas and jams all ballads (what a scandal). A madcap vandal crafts a small black ankh — a hand-stamp that can stamp a wax pad and at last plant a mark that sparks an ars magna (an abstract art that charts a phrasal anagram). A pagan skald chants a dark saga (a Mahabharata), as a papal cabal blackballs all annals and tracts, all dramas and psalms: Kant and Kafka, Max and Marat. A law as harsh as a fatwa bans all paragraphs that lack an A as a standard hallmark.

Mark Dunn’s 2001 epistolary novel Ella Minnow Pea is set on an island that successively bans letters of the alphabet. Its discourse begins with “Thank you for the lovely postcards” and dwindles to “No, mon, no! Nooooooooo!”

Vladimir Nabokov’s 1938 novel The Gift ends with the main character, a writer, resolving to write a book about his experiences in the novel, thus promoting himself from a character to the author.

In Norman Mailer’s short story “The Notebook,” a writer’s girlfriend accuses him of being only an observer, not a participant in life. This gives him an idea, which he scribbles into his notebook: Writer accused of being observer, not participant in life by girl. Gets idea he must put in notebook. Does so, and brings the quarrel to a head. Girl breaks relationship over this. The girl breaks up with him over this.

The first story in John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse is a strip of paper: One side bears the words ONCE UPON A TIME THERE, the other WAS A STORY THAT BEGAN. The reader is instructed to cut this out and fashion it into a Möbius strip that reads “Once upon a time there was a story that began ‘Once upon a time there was a story that began “Once upon a time there was a story that began …”‘”

“It’s short on character, it’s short on plot, but above all, it’s short,” Barth told an interviewer. “And it does remind us of the infinite imbeddedness of the narrative impulse in human consciousness.”

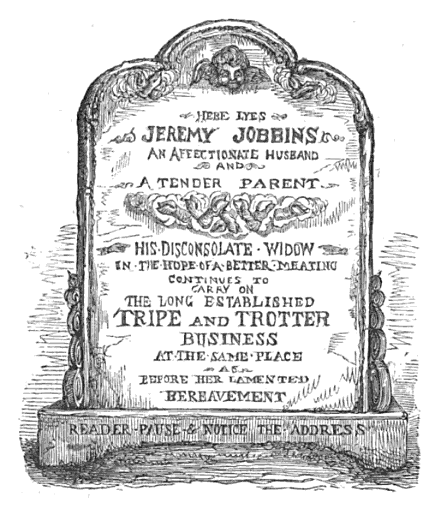

In Jean-Louis Bailly’s 1990 novel La Dispersion des cendres, an embittered mystery writer publishes a sensational novel whose cover bears the warning IF YOU BUY THIS BOOK, YOU ARE A MURDERER. IF YOU READ IT, YOU WILL KNOW WHY. When the royalties reach a certain sum, they automatically send into action an assassin who shoots the writer.

Who done it? You did! “As cause and instrument of the murder, fully aware of perpetrating it, the reader — or at least the buyer — is in every sense the guilty party.”

(Thanks, Ole and Harold.)