Last November, Jacob and Bonnie Richter of West Palm Beach, Fla., drove their motor home to Daytona Beach to attend an RV rally. Their cat, Holly, bolted when Bonnie’s mother opened the door, and could not be found after several days’ search. Finally the Richters returned home.

On New Year’s Eve, Holly was spotted “barely standing” in a backyard about a mile from the Richters’ house in West Palm Beach. The 4-year-old tortoiseshell had traveled 200 miles over two months to return to her hometown. She was identified both by the black-and-brown harlequin patterns in her fur and by an implanted microchip.

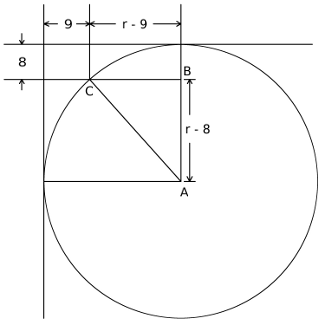

No one is quite sure how cats navigate across such long distances. Like other animals they may rely to some extent on magnetic fields, olfactory cues, and the sun, but generally cat navigation seems surest over short distances. In a 1954 study in Germany, cats were placed in a circular maze with exits positioned every 15 degrees; a cat exited most reliably in the direction of home if home was less than 5 kilometers away.

But at least some cats are capable of much greater feats. British cat biologist Roger Tabor cites “Ninja,” a cat who found his way from Mill Creek, Wash., to his old home in Farmington, Utah, in 1997; Howie, an indoor Persian cat who was left with relatives and traveled 1,000 miles across Australia to return to his family’s home in 1978; and a Russian tortoiseshell who traveled 325 miles from Moscow to her owner’s mother’s house in Voronezh in 1989.

Those exploits, and Holly’s, remain unexplained. “We haven’t the slightest idea how they do this,” cat behaviorist Jackson Galaxy told the New York Times in January. “Anybody who says they do is lying, and, if you find it, please God, tell me what it is.”