Last year Grant Maierhofer published Ebb, a novel written entirely without the letter A:

Ben went to school, worked in the Co-op, tried to write some but liked to be close with his friends. His friends comprised this kind of collective, this unity of spirit. Ben studied history. His friends studied too, some music, some writing, some science. They didn’t hope to extend their lives beyond this though, which left them odd. People who study, who hope to write, who hope to sing, who hope to push something through of their spirit, they often wish to flee, to go to New York, somewhere more, somewhere living, somewhere electric. These friends though they’d decided to let this be enough, their little communion with themselves, their communion of the work, which Ben enjoyed endlessly.

To describe the project, he wrote a thousand-word essay, itself without the letter A:

Why write the book? Good question. Possibly to try something out. To see where something brings you, then the things beyond this something. People write things. Sure, of course they do. People write things frequently. I write things, hm, since I like to figure the writing out. I bring problems on myself, then figure some route out of the box. The box? Stupid. Out of the box, outside the box? So stupid. Then how would you put it? The problem could be this cell, this thing you built surrounding your work. The problem could be the cell, then your working through it could be the tunneling out. This is nice. This is the thing, sure.

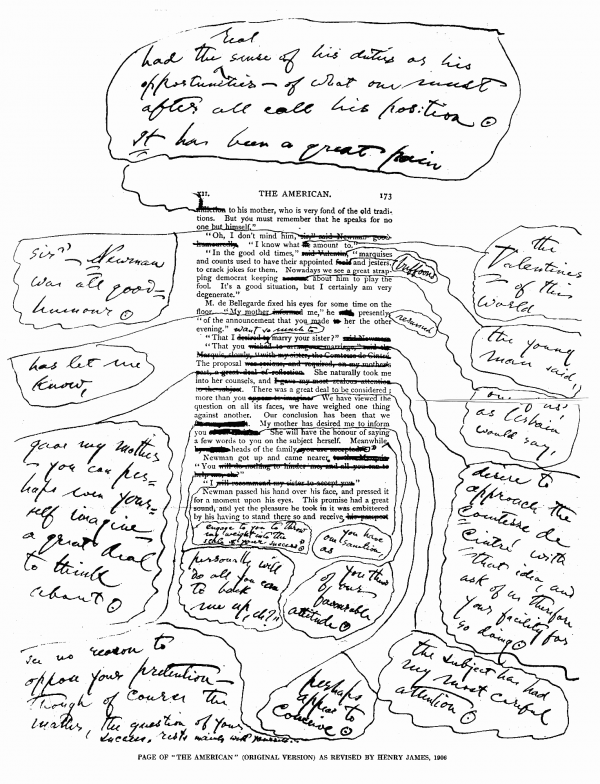

The essay and a longer excerpt are here. See The Void, The Great Gadsby, and Dead Letters.