Here are six new lateral thinking puzzles — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

Here are six new lateral thinking puzzles — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

In To Predict Is Not to Explain, mathematician René Thom describes a lunch at which psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan responded strongly to his statement that “Truth is not limited by falsity, but by insignificance.” Thom described the idea later in a drawing:

At the base, one finds an ocean, the Sea of the Insignificance. On the continent, Truth is on one side, Falsehood on the other. They are separated by a river, the River of Discernment. It is indeed the faculty of discernment that separates truth from falsehood. It’s Aristotle’s notion: the capacity for contradiction. It’s what separates us from animals: When information is received by them, it’s instantly accepted and it triggers obedience to its message. Human beings, however, have the capacity to withdraw and to question its veracity.

Following the banks of this river, which flows into the Sea of Insignificance, one travels along a coastline that is slightly concave: Situated at one end is the Slough of Ambiguity; at the other end is the Swamp of La Palice. At the head of the river delta, one sees the Stronghold of Tautology: That’s the stronghold of the logicians. One climbs a rampart towards a small temple, a kind of Parthenon: that’s Mathematics.

To the right, one finds the Exact Sciences: Up in the mountains that surround the bay is Astronomy, with an observatory topping its temple; at the far right stand the giant machines of Physics, the accelerator rings at CERN; the animals in their cages indicate the laboratories of Biology. Out of all this, there emerges a creek that feeds into the Torrent of Experimental Science, which flows into the Sea of Insignificance.

To the left is a wide path climbing towards the north west, up to the City of Human Arts and Sciences. Continuing along it one comes to the foothills of Myth. We’ve entered the kingdom of anthropology. Up at the top is the High Plateau of the Absurd. The spine signifies the loss of the ability to discern contraries, something like an excess of universal understanding which makes life impossible.

He explains the central idea in more detail starting on page 173 of the PDF linked above. “It’s something I’ve done to amuse myself, but it reflects something real, I think: The Logos, the possibility of representation by language, only comes into play for humanity in a rather limited number of situations … [O]ne begins to manufacture linguistic entities which do not correspond to real things. … That’s where the River of Discernment runs into the Fortress of Tautology, into the sewers. It’s become invisible, but at the surface it can smell pretty bad.”

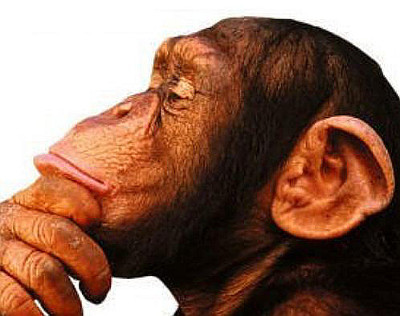

In isosceles triangle ABC, CD = AB and BE is perpendicular to AC. Show that CEB is a 3-4-5 right triangle.

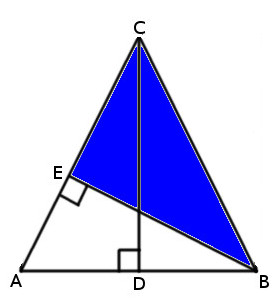

French philosopher Charles Fourier promoted a self-contained utopian society he called the phalanstère, or “grand hotel.” Each building would be a four-story apartment complex with two wings, one for children and noisy activities and the other containing ballrooms and meeting halls. Tasks would be assigned based on each member’s interests and desires, with higher pay going to undesirable jobs.

“In Fourier’s utopia, social harmony was guaranteed by assembling exactly 1,620 members, since he believed there were just twelve common passions that resulted in 810 types of character,” writes Damien Rudd in Sad Topographies. “In this way, every possible want, need and desire could be duly satisfied. It would be a society free of government, unfettered capitalism and the oppressive labour exploitation Fourier saw as the scourge of the modern world.”

The idea fell flat in Europe, but seven years after Fourier’s death in 1837 a group of idealistic followers built a community along the Ohio River based on his teachings. For $25 each subscribing family would get a timber house and a portion of land. It fell apart when Fourier’s promised “80,000 years of perfect harmony” failed to materialize.

In 1801, distressed at the “incoherence” and “bizarreness” of Paris street names, J.B. Pujoulx proposed turning the city into a stylized map of France in which the streets were named after towns and localities, with the size of each town reflected in the size of the street. Rivers and mountains would be represented by especially long streets that crossed several districts, “to provide an ensemble such that a traveller could acquire geographic knowledge of France within Paris, and reciprocally of Paris within France.”

How fine it would be, he wrote, “for the resident of the South of France to rediscover, in the names of the various districts of Paris, those of the place where he was born, of the town where his wife came into the world, of the village where he spent his early years!” Louis-Sébastien Mercier added, “Paris would be the map and hackney coaches the professors.”

Perhaps unwittingly, Pujoulx was echoing the cartographer Étienne Teisserenc, who in 1754 had offered a “Dictionary, Containing the Explanation of Paris or Its Map Turned into a Geographical Map of the Kingdom of France, to Serve as Introduction to General Geography; An Easy and New Method to Learn in a Practical Manner and on the Spot All the Principal Parts of the Kingdom as a Whole and Each Through the Others” (above). He suggested that this system might be extended to every state in the world.

When Yevgenia Ginzburg became a prisoner at Stalin’s Black Lake prison in the 1930s, she and her cellmate noticed a curious pattern. “On the days when our neighbor went to the washroom before us — this we could tell by the sound of the footsteps in the corridor — we always found the shelf sprinkled with tooth powder and the word ‘Greetings’ traced in it with something very fine like a pin, and as soon as we got back to our cell, a brief message was tapped on the wall. After that, he immediately stopped.”

After two or three days, she realized what it meant. “‘Greetings’! That’s what he’s tapping. He writes and taps the same word. Now we know how we can work out the signs for the different letters.” Ginzburg remembered a page from Vera Figner’s memoir in which she described an ancient prison code devised in the Czarist era — the alphabet was laid out in a square (this example is in English):

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y

Each letter is represented by two sets of taps, one slow and the other fast. The slow taps indicate the row and the fast the column. So, here, three slow taps followed by two fast ones would indicate the letter L. They tapped out “Who are you?”, and “Through the grim stone wall we could sense the joy of the man on the other side. At last we had understood! His endless patience had been rewarded.”

Prisoner Alexander Dolgun deciphered the same code in Moscow’s Lefortovo Prison, memorizing it with the help of matches. Finally he understood that the man in the next cell had been asking him “Who are you?” over and over — and felt “a rush of pure love for a man who has been asking me for three months who I am.”

(From Judith A. Scheffler, Wall Tappings, 1986.)

How I need a drink, alcoholic of course, after the tough chapters involving quantum mechanics!

That sentence is often offered as a mnemonic for pi — if we count the letters in each word we get 3.14159265358979. But systems like this are a bit treacherous: The mnemonic presents a memorable idea, but that’s of no value unless you can always recall exactly the right words to express it.

In 1996 Princeton mathematician John Horton Conway suggested that a better way is to focus on the sound and rhythm of the spoken digits themselves, arranging them into groups based on “rhymes” and “alliteration”:

_ _ _

3 point 1415 9265 35

^ ^

_ _ _ _ _ _ __

8979 3238 4626 4338 3279

** **^^ ^^ ****

. _ _ __ _ _ _ . _ .

502 884 197 169 399 375 105 820 974 944

^ ^ ^ ^

59230 78164

_ _ _ _

0628 6208 998 6280

^^ ^^ ^^

.. _ .._

34825 34211 70679

^ ^

He walks through the first 100 digits here.

“I have often maintained that any person of normal intelligence can memorize 50 places in half-an-hour, and often been challenged by people who think THEY won’t be able to, and have then promptly proved them wrong,” he writes. “On such occasions, they are usually easily persuaded to go on up to 100 places in the next half-hour.”

“Anyone who does this should note that the initial process of ‘getting them in’ is quite easy; but that the digits won’t then ‘stick’ for a long time unless one recites them a dozen or more times in the first day, half-a-dozen times per day thereafter for about a week, a few times a week for the next month or so, and every now and then thereafter.” But then, with the occasional brushing up, you’ll know pi to 100 places!

Maxims of George Washington:

“Wherever and whenever one person is found adequate to the discharge of a duty by close application thereto, it is worse executed by two persons, and scarcely done at all if three or more are employed therein.”

This is not a distorted photo — Italian designer Ferruccio Laviani devised this cabinet deliberately to create that effect.

The “Good Vibrations” storage unit, created for furniture brand Fratelli Boffi, was carved from oak by a CNC machine.

Below: In 2012, designers Estudio Guto Requena modeled three iconic Brazilian chair designs in 3D software and then fused those files with audio recorded in three São Paulo neighborhoods. The deformed designs were then sent to Belgium to be 3D-printed. They’re called “Nóize Chairs.”