chirography

n. one’s own handwriting or autograph; a style or character of writing

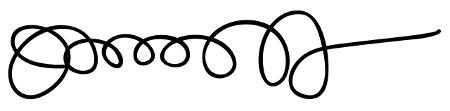

What is this? It’s the signature of Treasury Secretary Jack Lew. When Lew was nominated for the post in January 2013, it threatened to appear on all U.S. paper currency for the duration of his tenure.

Barack Obama said, “Jack assures me that he is going to work to make at least one letter legible in order not to debase our currency, should he be confirmed as secretary of the Treasury.” He did so — the current signature is below.

Lew’s predecessor, Timothy Geithner, had a similarly incomprehensible signature and produced a more legible version for the currency. “I took handwriting in the third grade in New Delhi, India,” he said, “so I probably did not get the best instruction on handwriting.”