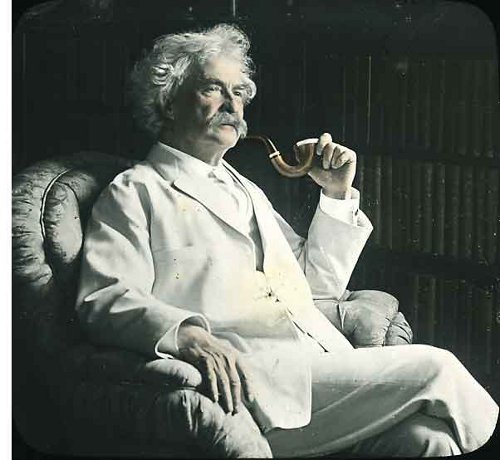

Mark Twain’s 3-year-old daughter Susie found this letter waiting for her on Christmas morning 1875:

Palace of St. Nicholas,

In the Moon,

Christmas Morning.

My Dear Susie Clemens:

I have received & read all the letters which you & your little sister have written me by the hand of your mother & your nurses; & I have also read those which you little people have written me with your own hands — for although you did not use any characters that are in grown people’s alphabets, you used the character which all children, in all lands on earth & in the twinkling stars use; & as all my subjects in the moon are children & use no character but that, you will easily understand that I can read your & your baby sister’s jagged & fantastic marks without any trouble at all. But I had trouble with those letters which you dictated through your mother & the nurses, for I am a foreigner & cannot read English writing well. You will find that I made no mistakes about the things which you & the baby ordered in your own letters — I went down your chimney at midnight & when you were asleep, & delivered them all, myself — & kissed both of you, too, because you are good children, well trained, nice-mannered, & about the most obedient little people I ever saw. But in the letters which you dictated, there were some words which I could not make out, for certain, & one or two small orders which I couldn’t fill because we ran out of stock. Our last lot of kitchen furniture for dolls had just gone to a very poor little child in the North Star, away up in the cold country above the Big Dipper. Your mama can show you that star, & you will say, ‘Little Snow Flake (for that is the child’s name,) I’m glad you got that furniture, for you need it more than I.’ That is, you must write that, with your own hand, & Snow Flake will write you an answer. If you only spoke it, she wouldn’t hear you. Make your letter light & thin, for the distance is great & the postage very heavy.

There was a word or two in your mama’s letter which I couldn’t be certain of. I took it to be ‘trunk full of doll’s clothes?’ Is that it? I will call at your kitchen door about nine o’clock this morning to inquire. But I must not see anybody, & I must not speak to anybody but you. When the kitchen door-bell rings, George must be blindfolded & sent to open the door, & then he must go back to the dining room or the china closet & take the cook with him. You must tell George he must walk on tip-toe and not speak — otherwise he will die some day. Then you must go up to the nursery & stand on a chair or the nurse’s bed, & put your ear to the speaking tube that leads down to the kitchen, & when I whistle through it, you must speak in the tube & say, ‘Welcome, Santa Claus!’ Then I will ask whether it was a trunk you ordered or not? If you say it was, I shall ask you what color you want the trunk to be. Your mama will help you to name a nice color, & then you must tell me every single thing, in detail, which you want the trunk to contain. Then when I say ‘Good bye & a Merry Christmas to my little Susie Clemens!’ You must say, ‘Good bye, good old Santa Claus, & thank you very much — & please tell that little Snow Flake I will look at her star to-night & she must look down here — I will be right in the west bay-window; & every fine night I will look at her star & say, I know somebody up there, & like her, too.’ Then you must go down in the library, & make George close all the doors that open into the main hall, & everybody must keep still for a little while. I will go to the moon & get those things, & in a few minutes I will come down the chimney which belongs to the fire-place that is in the hall — if it is a trunk you want, because I couldn’t get such a thing as a trunk down the nursery-chimney, you know.

People may talk, if they want to, till they hear my footsteps in the hall — then you tell them to keep quiet a little while till I go back up the chimney. Maybe you will not hear my foot steps at all — so you may go now & then & peep through the dining room doors, & by & by you will see that thing which you want, right under the piano in the drawing room — for I shall put it there. If I should leave any snow in the hall, you must tell George to sweep it into the fireplace, for I haven’t time to do such things. George must not use a broom, but a rag — else he will die some day. You must watch George, & not let him run into danger. If my boot should leave a stain on the marble, George must not holy-stone it away. Leave it there always in memory of my visit; & whenever you look at it or show it to anybody you must let it remind you to be a good little girl. Whenever you are naughty, & somebody points to that mark which your good old Santa Claus’s boot made on the marble, what will you say, little Sweetheart?

Good-bye, for a few minutes, till I come down to the world & ring the kitchen door-bell.

Your loving

Santa Claus,

Whom people sometimes call ‘The Man in the Moon.’