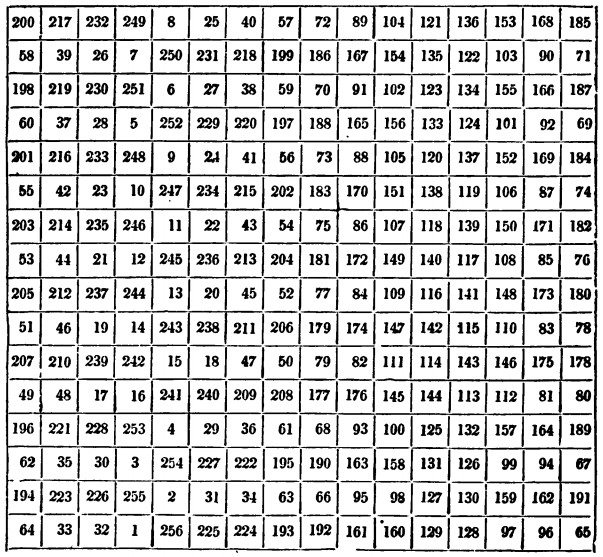

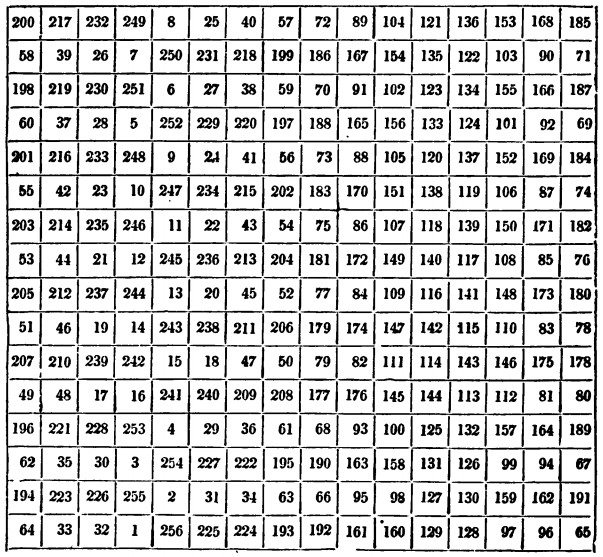

When a friend showed him a 16 × 16 magic square devised by Michel Stifelius, Ben Franklin went home and composed the square above, “not willing to be outdone.” An admirer describes its properties:

1. The sum of the sixteen numbers in each column or row, vertical or horizontal, is 2,056. — 2. Every half column, vertical or horizontal, makes 1,028, or just one half of the same sum, 2,056. — 3. Any half vertical row added to any half horizontal, makes 2,056. — 4. Half a diagonal ascending added to half a diagonal descending, makes 2,056, taking these half diagonals from the ends of any side of the square to the middle of it, and so reckoning them either upward, or downward, or sideways. — 5. The same with all the parallels to the half diagonals, as many as can be drawn in the great square: for any two of them being directed upward and downward, from the place where they begin to that where they end, make the sum 2,056; thus, for example, from 64 up to 52, then 77 down to 65, or from 194 up to 204, and from 181 down to 191; nine of these bent rows may be made from each side. — 6. The four corner numbers in the great square added to the four central ones, make 1,028, the half of any column. — 7. If the great square be divided into four, the diagonals of the little squares united, make, each, 2,056. — 8. The same number arises from the diagonals of an eight sided square taken from any part of the great square. — 9. If a square hole, equal in breadth to four of the little squares or cells, be cut in a paper, through which any of the sixteen little cells may be seen, and the paper be laid on the great square, the sum of all the sixteen numbers seen through the hole is always equal to 2,056.

Franklin wrote, “This I sent to our friend the next morning, who, after some days, sent it back in a letter with these words: ‘I return to thee thy astonishing or most stupendous piece of the magical square, in which’ — but the compliment is too extravagant, and therefore, for his sake as well as my own, I ought not to repeat it. Nor is it necessary; for I make no question but you will readily allow this square of 16 to be the most magically magical of any magic square ever made by any magician.”

(“Clavis,” “Magic Squares,” The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction 4:109 [Oct. 23, 1824], 293-294.) (Thanks, Walker.)

12/21/2020 UPDATE: The square appeared originally in 1767 in James Ferguson’s Tables and Tracts, Relative to Several Arts and Sciences and was reprinted a year later in the Gentleman’s Magazine. Only the second publication credits Franklin. I don’t have a date for Franklin’s purported composition, so I don’t know what to make of this. (Thanks, Tom.)