bibliobibuli

n. the sort of people who read too much

bibliobibuli

n. the sort of people who read too much

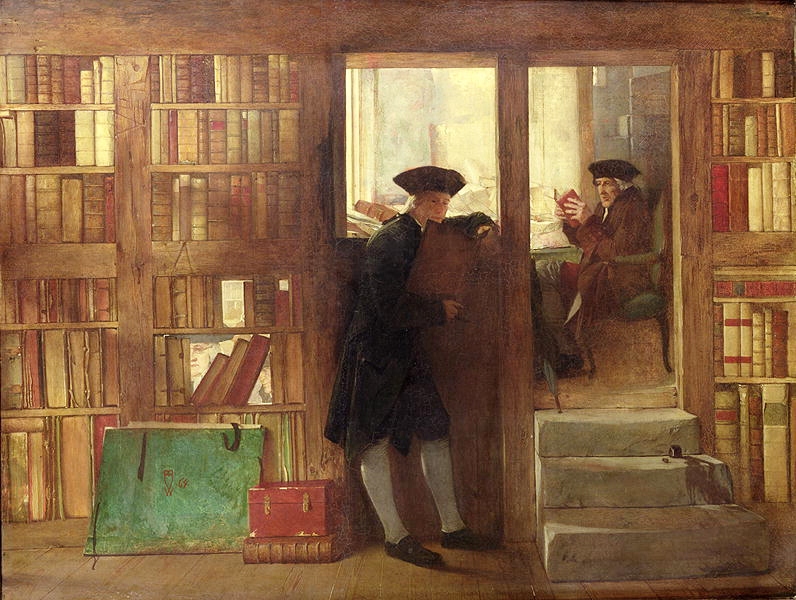

In 1850, England received a distinguished guest: A baby hippopotamus arrived at the London Zoo. Obaysch was an instant celebrity, attracting throngs of visitors while confounding his inexperienced keepers. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe his long tenure at the zoo, more than 4,000 miles from his Egyptian home.

We’ll also remark on a disappearing signature and puzzle over a hazardous hand sign.

In another case of press repression which succeeded only in creating a martyr, the editor of the Swedish newspaper Stockholms Posten, Captain Anders Lindeberg, was convicted of treason in 1834 for implying that King Karl Johan should be deposed. He was sentenced to death by decapitation, under a medieval treason law. When the King mitigated the sentence to three years in prison, Lindeberg decided to highlight the King’s repressive press policy by insisting upon his right to be beheaded and refusing to take advantage of the government’s attempts to encourage him to escape. Finally, in desperation, the King issued a general amnesty to ‘all political prisoners awaiting execution’, which applied only to Lindeberg. When the editor stubbornly insisted upon his right to execution, the government solved the problem by locking him out of his cell while he was walking in the prison courtyard and then refusing him re-entry.

— Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Censorship of the Arts and the Press in Nineteenth-Century Europe, 1989

(Thanks, Jason.)

[T]o deprive the meanest insect of life, without a good reason for so doing, is certainly criminal. By such an act, a man destroys, what neither he, nor all the united powers of the world can ever repair; and it may be attended with worse consequences than he can imagine. If superior beings had the same power over us, that we have over brutes, what misery might not one of them occasion to a whole nation, by destroying such an insect as a minister of state may appear to be in his eyes? If a child dismembers a bee, or an ant, he may, for any thing we know to the contrary, distress a whole common-wealth.

— James Granger, An Apology for the Brute Creation, or Abuse of Animals Censured, 1772

The United States minted nearly half a million copies of this 20-dollar gold coin in 1933, but when gold coins were disallowed as legal tender most of them were melted down. The mint saved two for the U.S. National Numismatic Collection, and 20 more were stolen. Of these, nine have now been destroyed, and 10 are held at Fort Knox. That means that a total of 13 specimens of the 1933 double eagle are known to exist, with only one in private hands. Shoe designer Stuart Weitzman, who had paid $7.6 million for that one in 2002, auctioned it last month to an anonymous collector for $18.9 million. That coin is unique: No other 1933 double eagle can be privately owned or legally sold.

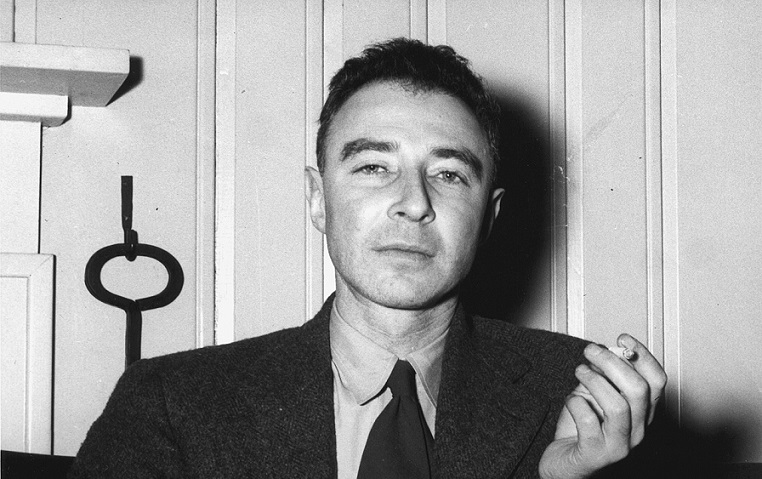

“To try to be happy is to try to build a machine with no other specification than that it shall run noiselessly.” — J. Robert Oppenheimer, Letters and Recollections, 1980

Here’s a macabre fad from Victorian Britain: headless portraits, in which sitters held their severed heads in their hands, on platters, or by the hair, occasionally even displaying the weapons by which they’d freed them.

Photographer Samuel Kay Balbirnie ran advertisements in the Brighton Daily News offering “HEADLESS PHOTOGRAPHS – Ladies and Gentlemen Taken Showing Their Heads Floating in the Air or in Their Laps.”

On Oct. 24 [1947] two University of Chicago students rattled into Reno., Nev. in a Model-A Ford to try the gambling. Their total resources: $100. Wasting no time, they went to the Palace Club, where they studiously made a chart of the recurrence of numbers on the roulette wheel. Then they went into action. Playing number 9, which their records indicated as the best possibility, they parlayed their $100 into $5,000 in 40 hours. At this point the manager became uneasy, switched the wheel. So the students moved on to Harold’s Club.

There they used the same system. Sure enough, their $5,000 rose to $14,500. But then, unaccountably, their system went sour. They dropped from $14,500 to $10,000 and kept going down. That was when the young theoreticians made the smartest move of all. They pocketed their winnings, packed up the Model-A and went home, ahead by $6,500.

(The students were Albert Hibbs and Roy Walford. Accounts vary as to their total takings; Hibbs claimed $12,000 on You Bet Your Life in 1959. They spent a year sailing around the Caribbean and then returned to their studies. Hibbs went on to become a JPL physicist and Walford a UCLA pathologist.)

Futility Closet is supported entirely by its readers. If you value this site, please consider making a contribution to help keep it going.

You can make a one-time donation on our Support Us page, or you can pledge a monthly contribution and get bonus posts and other rewards. You choose the amount to contribute, and you can change or cancel it at any time.

Thanks for your support, and thanks for reading!

Greg

British inventor William Cantelo had just developed an early machine gun when he disappeared from his Southampton home in the 1880s. A private investigator traced him to the United States but could learn nothing more of his whereabouts.

Shortly afterward, Cantelo’s sons came across a photograph of Hiram Maxim, an American inventor who’d moved to London and completed a similar-sounding machine gun of his own. The sons, struck at the similarity of the photographs, tried to accost Maxim at London’s Waterloo Station, but he departed on a train.

The similarity of the photographs may have been a coincidence — the two men were the same age, and both wore large Victorian beards. Maxim had complained in his autobiography of a “double” who had been impersonating him in the United States, but Maxim had a long history of successful patents, the first in 1866, long before Cantelo’s disappearance.

On the other hand, the disappearance has never been explained. Maxim eventually sold his gun to the British government. He died in 1916.