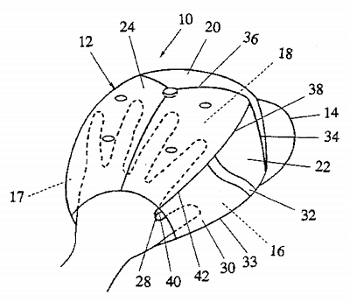

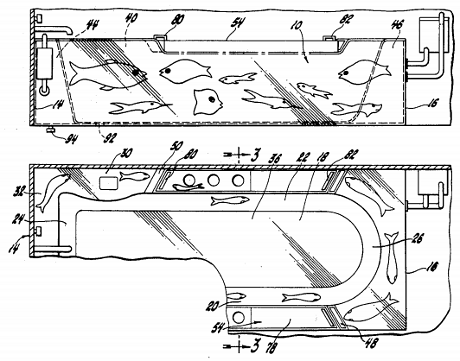

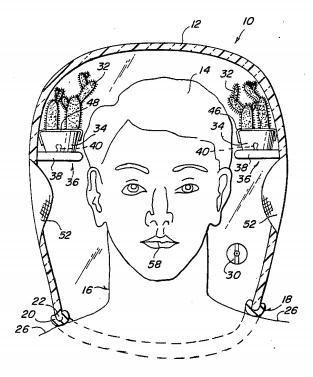

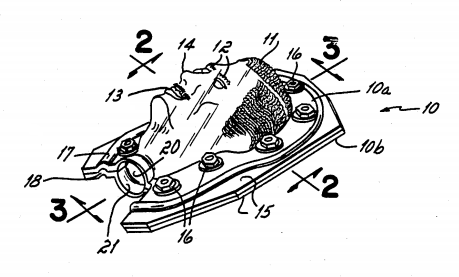

Richard Tweddell III patented this “method and apparatus for molding fruits” in 1987. While fruit is growing on a plant, you enclose it in a transparent mold. As the fruit gets larger, it gradually fills the cavity “and in doing so conforms with remarkable fidelity to the internal details of the mold.” He sells it pretty well:

They can be caused to grow in the image of a particular person; in the shape of a different type of produce (e.g., a summer squash grown in the shape of an ear of corn); a fanciful shape such as a heart, or a bottle of pop; or other simple or even quite detailed shapes. A zucchini in the likeness of Clark Gable, for example, complete with mustache, would be no ordinary sight on the dinner table. Similarly, a Christmas tree ornament formed of a small, configured gourd is a very distinctive novelty.

Well, that’s true. Tweddell also suggests that turkey-shaped fruit might be enjoyed at Thanksgiving, or pumpkin-shaped fruit at Halloween. And “the invention also makes possible the concept of molding the logo of, say, a pickle company, directly into the side of a pickle itself.”