In Saint Petersburg, an equestrian statue of Peter the Great stands atop an enormous pedestal of granite. The statue was conceived by French sculptor Étienne Maurice Falconet, who envisioned the horse rearing at the edge of a great cliff under Peter’s restraining hand.

Casting the horse and rider was relatively easy; harder was finding a portable cliff. In September 1768 a peasant led authorities to an enormous boulder half-buried near the village of Konnaia, four miles north of the Gulf of Finland and about 13 miles from the center of Saint Petersburg. Falconet proposed cutting it into pieces, but Catherine the Great, who wanted to show off Russia’s technological potential, ordered it moved whole, “first by land and then by water.”

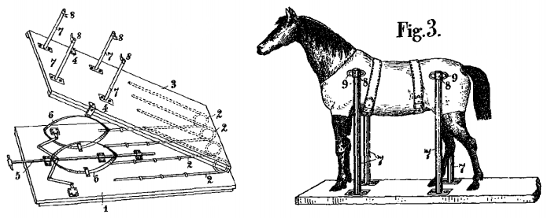

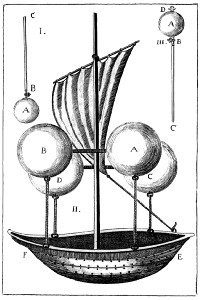

Incredibly, she got her wish. The unearthed boulder measured 42 feet long, 27 feet wide, and 21 feet high; even when trimmed by a third it weighed an estimated 3 million pounds. But it was mounted on a chassis and rolled along atop large copper ball bearings, a “mountain on eggs,” as stonecutters worked continuously to shape it. When they reached the Gulf of Finland it was transferred precariously to a barge mounted between two cutters of the imperial navy, which carried it carefully to the pier at Senate Square, where it was installed in 1770, after two years of work. The finished pedestal stands 21 feet tall.

“The daring of this enterprise has no parallel among the Egyptians and the Romans,” marveled the Journal Encyclopédique; the English traveler John Carr said that the feat astonished “every beholder with a stupendous evidence of toil and enterprise, unparalleled since the subversion of the Roman empire.” It remains the largest stone ever moved by man.