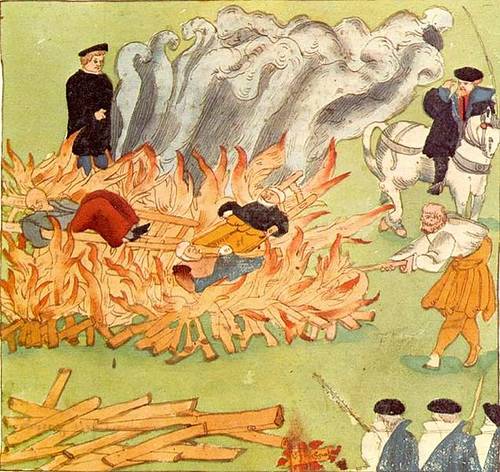

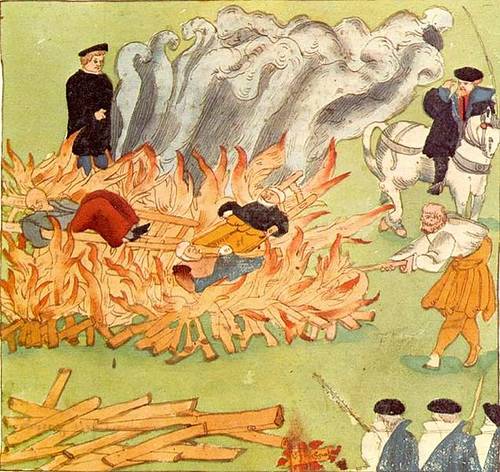

Testimony given by James Device against his grandmother, Elizabeth Sothernes, in a trial for witchcraft, Lancaster, England, April 27, 1612:

THE sayd Examinate Iames Deuice sayth, that about a month agoe, as this Examinate was comming towards his Mothers house, and at day-gate of the same night, Euening. this Examinate mette a browne Dogge comming from his Graund-mothers house, about tenne Roodes distant from the same house: and about two or three nights after, that this Examinate heard a voyce of a great number of Children screiking and crying pittifully, about day-light gate; and likewise, about ten Roodes distant of this Examinates sayd Graund-mothers house. And about fiue nights then next following, presently after daylight, within 20. Roodes of the sayd Elizabeth Sowtherns house, he heard a foule yelling like vnto a great number of Cattes: but what they were, this Examinate cannot tell. And he further sayth, that about three nights after that, about midnight of the same, there came a thing, and lay vpon him very heauily about an houre, and went then from him out of his Chamber window, coloured blacke, and about the bignesse of a Hare or Catte. And he further sayth, that about S. Peter’s day last, one Henry Bullocke came to the sayd Elizabeth Sowtherns house, and sayd, that her Graund-child Alizon Deuice, had bewitched a Child of his, and desired her that she would goe with him to his house; which accordingly she did: And therevpon she the said Alizon fell downe on her knees, & asked the said Bullocke forgiuenes, and confessed to him, that she had bewitched the said child, as this Examinate heard his said sister confesse vnto him this Examinate.

Sothernes died in prison as her trial approached, but her family barely outlived her. James, his mother, and his sister also confessed to witchcraft and were executed on Aug. 18.