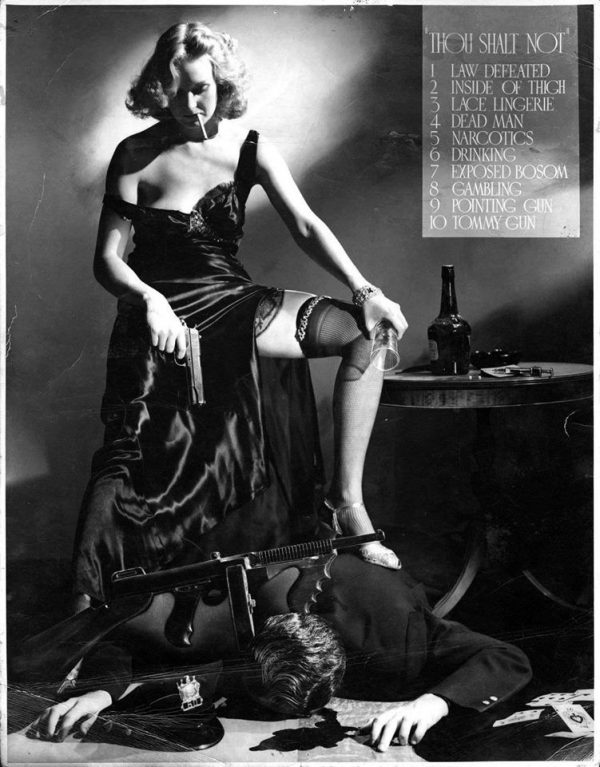

Paramount photographer A.L. Schafer set up this shot in 1940 to simultaneously flout 10 provisions of the Hays Code, Hollywood’s guideline for self-censorship between 1934 and 1968.

When Schafer entered the photo in an industry competition and organizers threatened him with a fine, he pointed out that the judges were hoarding all 18 prints he’d submitted.

(Via Open Culture.)

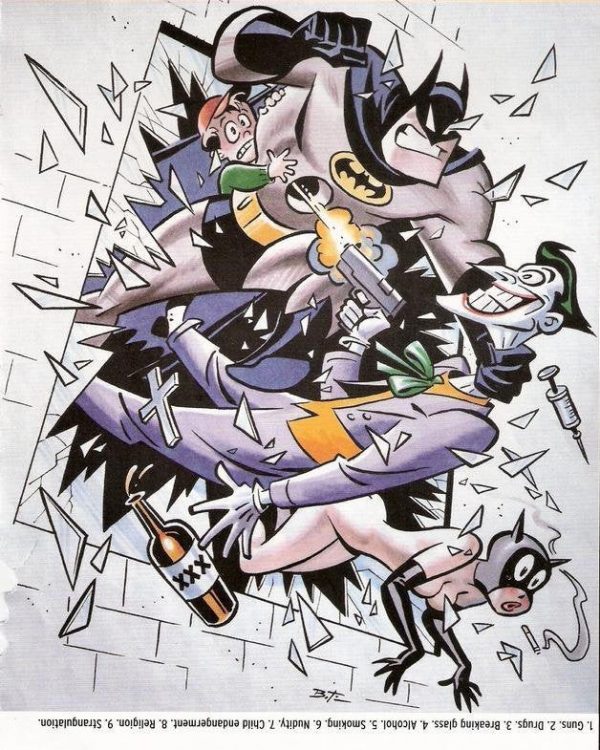

03/07/2021 UPDATE: Artist Bruce Timm made a similar image combining nine themes barred from Batman: The Animated Series: guns, drugs, breaking glass, alcohol, smoking, nudity, child endangerment, religion, and strangulation: