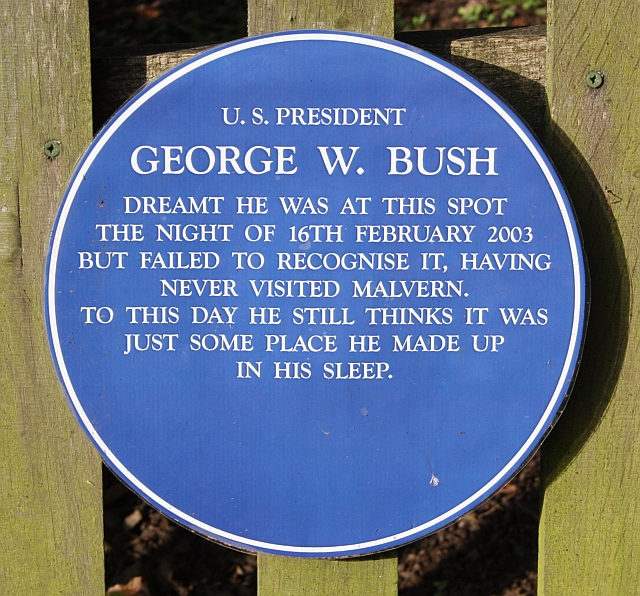

Plaque at St. Ann’s Well, Malvern, Worcestershire, August 2009.

Plaque at St. Ann’s Well, Malvern, Worcestershire, August 2009.

In 1880, an 800-year-old yew tree was threatening the west wall of the church of St Andrew at Buckland in Dover. The community called in landscape gardener William Barron, who solved the problem by boring tunnels under the trunk and then raising the tree’s entire 55-ton mass onto rollers by means of powerful screw jacks. Giant windlasses could then haul the tree 203 feet across the churchard to a safer location.

“The scale of this operation was probably never matched,” writes G.M.F. Drower in Garden of Invention, his 2003 history of gardening innovations. “[A]nd Barron, who had been rather more apprehensive than he let on, later admitted that all the other trees he had moved had been ‘chickens compared to the Buckland Yew.'”

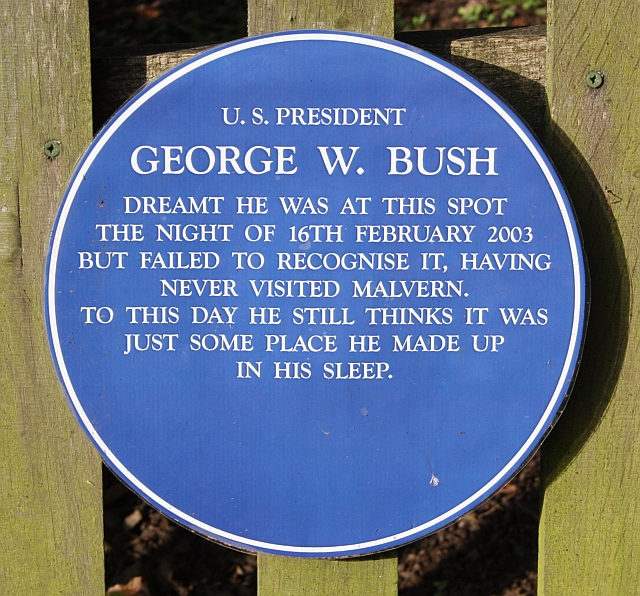

By Wikimedia user Cmglee, a visual proof that a3 – b3 = (a – b)(a2 + ab + b2):

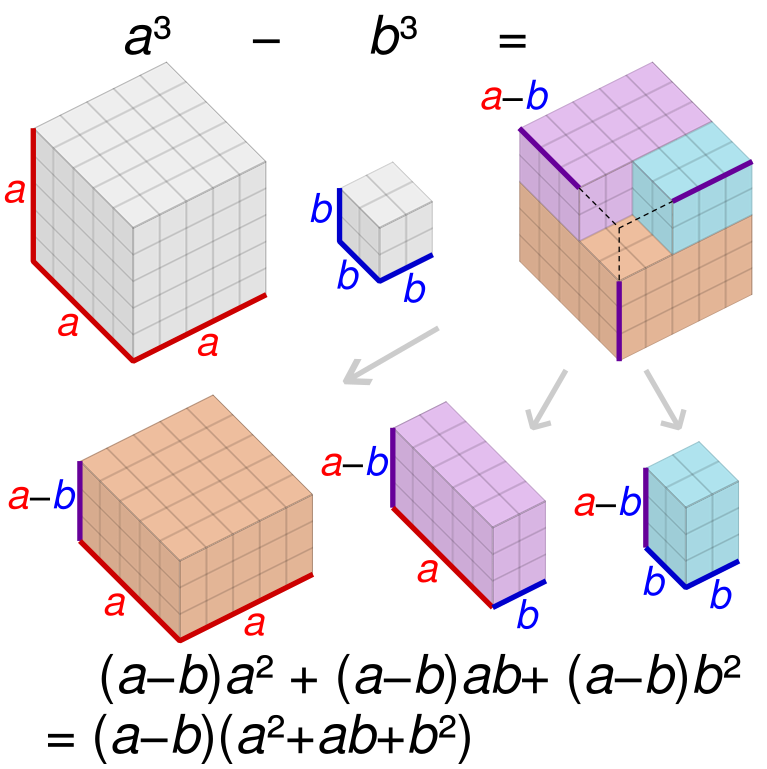

Where did the familiar syllables of solfège (do, re, mi) come from? Eleventh-century music theorist Guido of Arezzo collected the first syllable of each line in the Latin hymn “Ut queant laxis,” the “Hymn to St. John the Baptist.” Because the hymn’s lines begin on successive scale degrees, each of these initial syllables is sung with its namesake note:

Ut queant laxīs

resonāre fibrīs

Mīra gestōrum

famulī tuōrum,

Solve pollūti

labiī reātum,

Sancte Iohannēs.

Ut was changed to do in the 17th century, and the seventh note, ti, was added later to complete the scale.

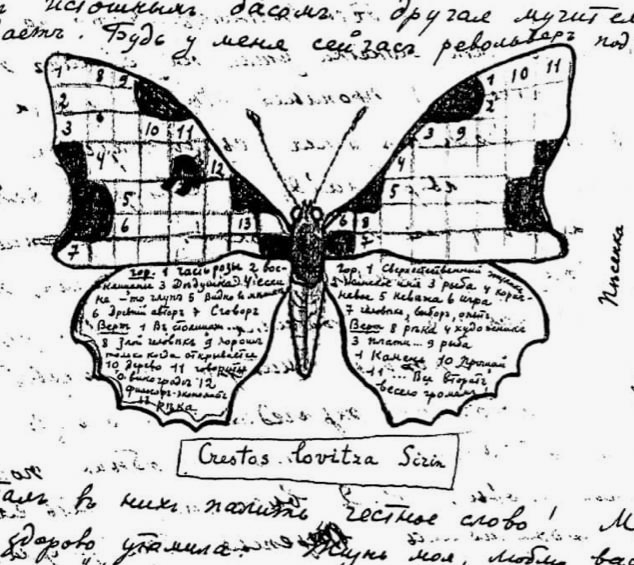

Vladimir Nabokov composed this puzzle for his wife Véra in 1926. The title, “Crestos lovitxa Sirin,” roughly means “Nabokov’s crossword”: krestlovitska approximates the Russian kreslovitsa, “cross” plus “words”, and Sirin is a pseudonym Nabokov often used, a reference to the creatures of Russian mythology. The upper half of each wing contains the grid, the lower the clues.

Nabokov, a trained entomologist, had published the first crossword in Russian two years earlier. Forty years later, in the Paris Review, he likened writing a novel to creating a crossword: “The pattern of the thing precedes the thing. I fill in the gaps of the crossword at any spot I happen to choose.”

(Adrienne Raphel, The Crossword Mentality in Modern Literature and Culture, dissertation, Harvard University, 2018.)

Georges Perec worked out that the French phrase andin basnoda a une epouse qui pue (“Andin Basnoda has a smelly wife”) reads the same upside down.

Typographer Pierre di Sciullo created a typeface to honor this ambigram — he called it Basnoda.

Each year since 1993, the Literary Review has presented a Bad Sex in Fiction Award “to draw attention to the crude, tasteless, often perfunctory use of redundant passages of sexual description in the modern novel, and to discourage it.” Here’s 2013’s winner, Manil Suri, in his novel The City of Devi:

Surely supernovas explode that instant, somewhere, in some galaxy. The hut vanishes, and with it the sea and the sands — only Karun’s body, locked with mine, remains. We streak like superheroes past suns and solar systems, we dive through shoals of quarks and atomic nuclei. In celebration of our breakthrough fourth star, statisticians the world over rejoice.

In a retrograde analysis puzzle, one tries to deduce the history of a game from the current state of play. The most familiar examples concern chess, but Smith College mathematician Jim Henle worked out that it can also be done in baseball. This is the batting order of the Mudville Slugs:

We’re told also that in the ninth inning Casey came to bat for the fourth time, while the bases were loaded with two men out. Casey struck out, leaving the team with another loss. How many runs did Mudville score altogether?

By Nevit Dilmen. How many sticks do you see?

Memorable excerpts from the detective fiction of Michael Avallone (1924-1999):

This and my recent post on Robert Leslie Bellem were inspired by Bill Pronzini, who has written two appreciations of rapturously bad mystery fiction.