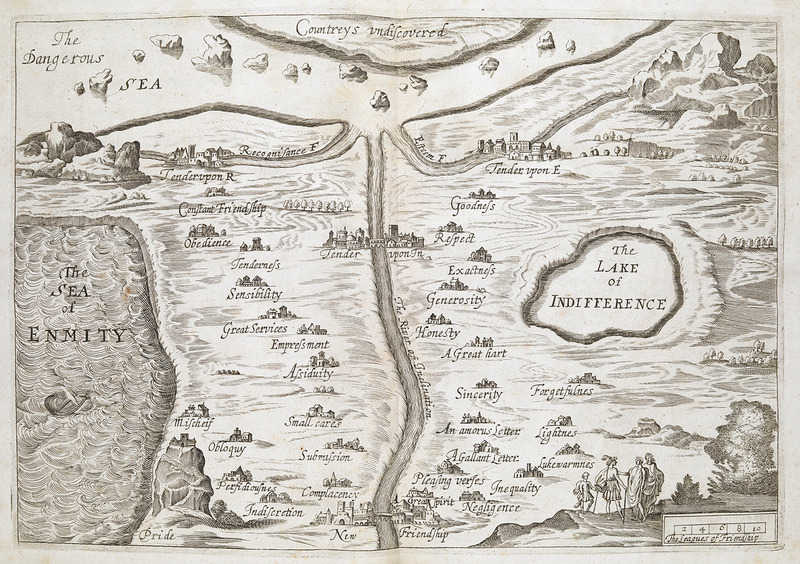

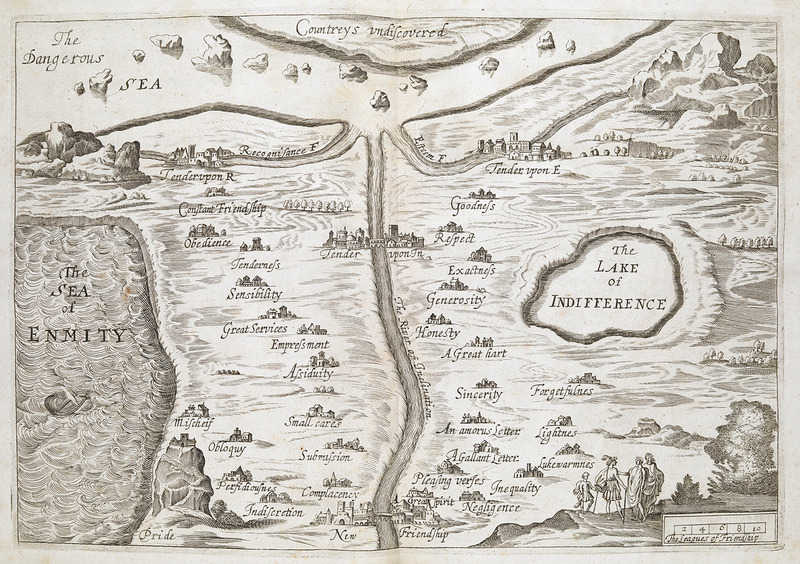

Here’s why your relationships keep falling apart — finding the right course is almost impossible. The French noblewoman Madeleine de Scudéry devised this map of the “Land of Tenderness” in 1653, for her romance Clelia. A couple starting at New Friendship, at the bottom, can take any of four roads. Two of them stay safely near the River of Inclination: One of these passes through Complacency, Submission, Small Cares, Assiduity, Empressment, Great Services, Sensibility, Tenderness, Obedience, and Constant Friendship to reach “Tender Upon Recognisance”; the other passes through Great Spirit, Pleasing Verses, A Gallant Letter, An Amorous Letter, Sincerity, A Great Heart, Honesty, Generosity, Exactness, Respect, and Goodness to reach “Tender Upon Esteem.” But there are two more dangerous outer roads: One passes through Indiscretion, Perfidiousness, Obloquy, and Mischief to end in the Sea of Enmity; the other through Negligence, Inequality, Lukewarmness, Lightness, and Forgetfulness to reach the Lake of Indifference. And even lovers who reach a happy outcome may go too far, passing into the Dangerous Sea and perhaps beyond it into Countreys Undiscovered.

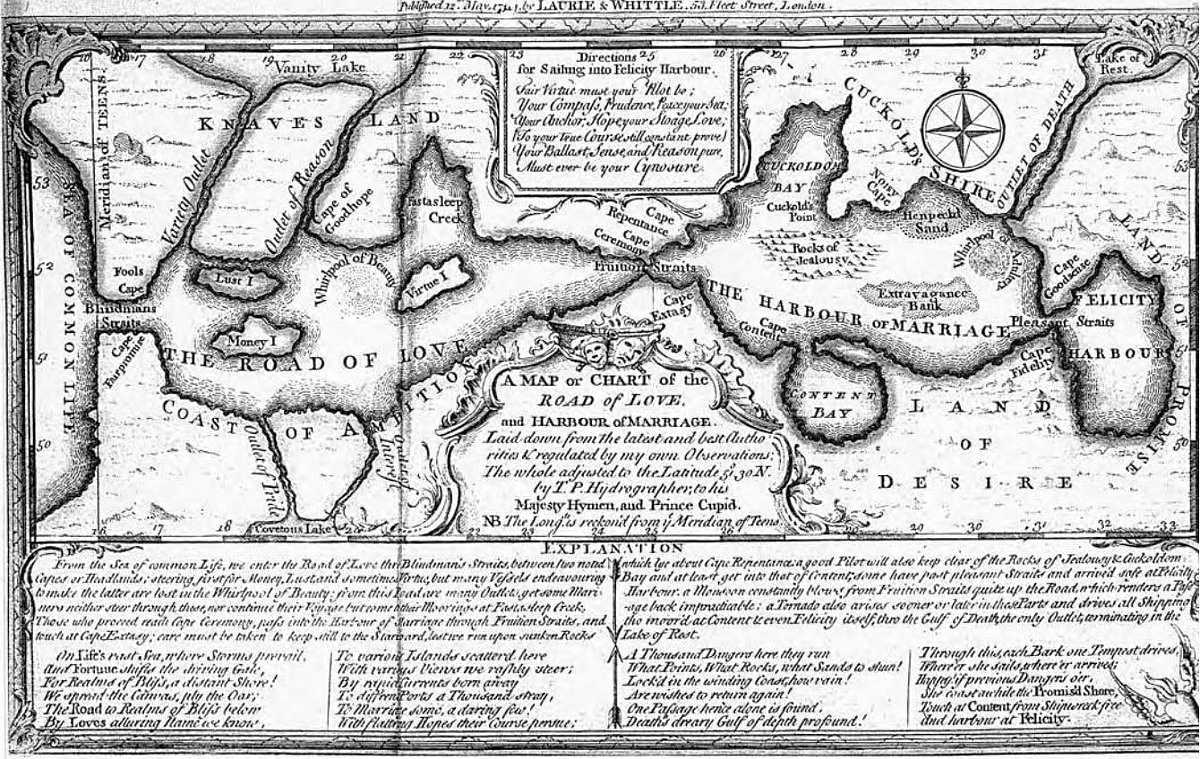

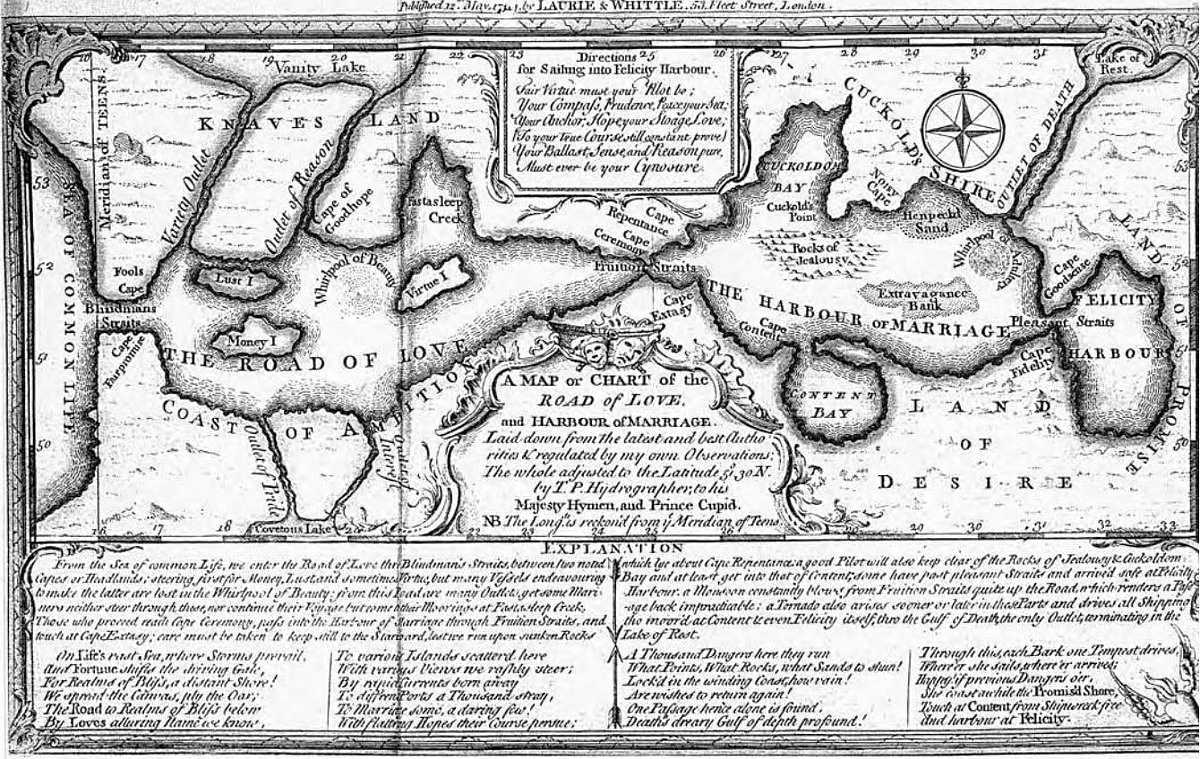

Even worse is this vision, a “Map or Chart of the Road of Love, and Harbour of Marriage” published by “T.P. Hydrographer, to his Majesty Hymen, and Prince Cupid” in 1772. The traveler has to find the way from the Sea of Common Life at left to Felicity Harbour and the Land of Promise at right, and the only way to get there is by the Harbour of Marriage, in which lurk Henpecked Sand and the disastrous Whirlpool of Adultery. The explanation at the bottom describes the treacherous course:

From the Sea of Common Life, we enter the Road of Love thro’ Blindmans Straits, between two noted Capes or Headlands; steering first for Money, Lust, and sometimes Virtue, but many Vessels endeavouring to make the latter are lost in the Whirlpool of Beauty; from this Road are many outlets, yet some Mariners neither steer through these, nor continue their Voyage but come to their Moorings at Fastasleep Creek. Those who proceed reach Cape Ceremony, pass into the Harbour of Marriage through Fruition Straits and touch at Cape Extasy; care must be taken to keep still to the Starboard, lest we run upon sunken Rocks which lye about Cape Repentance; a good Pilot will also keep clear of the Rocks of Jealousy & Cuckoldom Bay and at least get into that of Content, some have past pleasant Straits and have arrived safe at Felicity Harbour, a Monsoon constantly blows from Fruition Straits quite up the Road, which renders a Passage back impracticable; a Tornado also arises sooner or later in those Parts and drives all Shipping tho moor’d at Content & even Felicity itself, thro the Gulf of Death, the only Outlet, terminating in the Lake of Rest.

The map provides some general advice: “Your Virtue must your Pilot be; Your Compass, Prudence, Peace your Sea; Your Anchor, Hope; your Sto[w]age, Love; (To your true Course still constant prove) Your Ballast, Sense, and Reason pure, Must ever be your Cynosure.”

(From Ashley Baynton-Williams, The Curious Map Book, 2015.)